Fracking gasholes

We know you know

For a million reasons

We must say no no no

No no no no no.

—‘Fracking Gasholes’ by XOEarth

Williamsport is a town of 29,000 in Pennsylvania’s upper Susquehanna Valley. When I decided to stop there in the spring of 2012 on the way to upstate New York, I figured it for a place lost in time—a sleepy burg still guided by small-town values (Williamsport hosts the Little League World Series every summer) but with the sad and deserted appearance you’d expect in an area where the main industry, steelmaking, receded from sight in the 1970s.

That is why I was surprised to find a new mall on its outskirts, as well as construction sites for banks and office buildings. Instead of a boarded-up downtown, there were new restaurants opening. The hotel was also bustling—and expensive. I had had trouble finding parking in a lot jammed with pickup trucks and SUVs. In the hotel elevator were two men in green jumpsuits, both carrying tool bags of a kind I recognized from crews working on offshore oil rigs in the North Sea. They were natural-gas drillers coming back for some sleep after a long night working in the gas field.

They were frackers.

Williamsport sits on the edge of the Marcellus Shale area, the second-largest natural-gas find in the world. It stretches across most of Pennsylvania and into New York, West Virginia, Ohio, and Maryland. Most of it was inaccessible until a decade ago, when a combination of new extraction technologies—including hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” and horizontal drilling—opened up the shale to energy development.

Since 2002, fracking has generated in Pennsylvania more than 24,000 drilling jobs and some 200,000 other support jobs in trucking, construction, and infrastructure, according to the state’s Department of Labor and Industry. Wages in the gas field average $62,000 a year—$20,000 higher than the state average.

To Pennsylvania, fracking has brought in $4 billion in investment, including a steady flow of income to local landowners and local governments leasing mineral rights to their land. According to National Resources Economics, Inc., full development of the Marcellus Shale could bring another 211,000 jobs to this one state alone, not to mention other states on the formation, including New York.

But there will be no such jobs in the state of New York. In December, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a complete ban on the use of hydraulic fracturing. The cost of that move was already foreshadowed three years ago when I drove across the border from Pennsylvania into New York. The busy modern highway coming out of Williamsport, U.S. Route 15, shrinks down into a meandering, largely empty two-lane road. On the way to Ithaca, I passed through miles of a deserted rural landscape dotted with collapsing barns and tumble-down houses reminiscent of Appalachia.

The one thing that broke the dismal monotony were the signs, many painted by hand, that had sprouted up along the road and in the fields, all saying the same thing: Ron Paul for President. The state was then in its fifth year of a moratorium on fracking, and that moratorium had turned upstate New York’s rural residents into libertarians. Bitter ones, at that. They didn’t particularly care about Ron Paul’s views on Israel or the Federal Reserve. All they wanted was a chance to collect the lucrative fees a gas company would pay them to drill on their land; they would have voted for anyone who would help them make their land generate an income again for themselves and their families.

This sort of gain is precisely what the left’s war on fracking (which has scored its most significant victory so far with Cuomo’s permanent ban) aims to prevent. It is nothing less than a policy of selective immiseration.

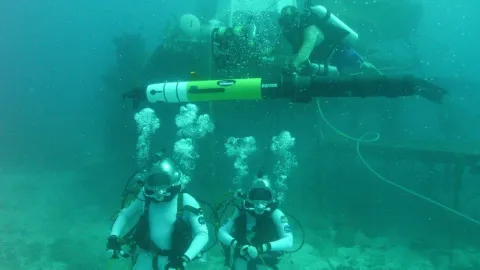

Fracking—a technique that uses a mixture of chemicals, sand, and water to break apart deep formations of oil- and gas-rich shale rock and draw it to the surface—is the most important American industrial enterprise of the 21st century. It joins the automobile industry, aircraft and aerospace, the computer and the digital revolution, as one of America’s great successes in technological innovation, productivity, and entrepreneurial flair. Like other industrial revolutions, including the first in 18th-century Britain, the fracking revolution is bringing about enormous changes in how we live—and sharply altering the nation’s income-distribution curve.

The fracking revolution has also brought America’s oil and gas industry back to life. In 2000, fracking accounted for less than 3 percent of all oil and natural-gas production in the United States, which was then importing more than 60 percent of its oil. Today, fracking accounts for more than 40 percent, and that percentage is going steadily upward, as the U.S. replaces one country after another on the list of the world’s biggest oil and gas producers. Our oil imports from OPEC countries have shrunk by half.

Indeed, the production gushing from America’s shale oil and gas deposits—from Eagle Ford in Texas to the Marcellus Formation in Pennsylvania and the Bakken oil field in North Dakota—doesn’t just promise the long-elusive goal of energy independence. It points to an energy dominance and economic power that the United States hasn’t seen for 100 years, since the heyday of John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil.

The difference is that instead of that power being lodged in a single megacorporation or the Seven Sisters of the 1950s (Mobil, Shell Esso, etc.), the fracking revolution is being created by hundreds of smaller, more agile independents who are transforming the technology as fast as they are pumping the oil and natural gas out of the ground.

They are also pumping out jobs by the tens of thousands. It is no longer the case that good-paying blue-collar employment in America is on the verge of extinction. Fracking employs thousands of people in physically demanding jobs that require no college degree and pay, in many cases, six figures.

In North Dakota, where fracking has turned the Bakken Shale formation into the most productive oil patch in the country, an entry-level job hauling water and helping to move rigs and machinery averages $67,000 a year. A well specialist with a couple of years experience will be looking at a $100,000 salary, while a directional driller—the highest job a fracking employee can hold without a B.A.—earns close to $200,000.

Overall, the fracking boom has driven up North Dakota’s per capita income to $57,367 in 2012—the highest in the nation save for Washington D.C. The per capita figure has jumped 31 percent since 2008, the year after the fracking boom got under way, compared with 10 percent for frackless South Dakota.

The other beneficiaries are private landowners, many of them farmers. They have been able to lease out the mineral rights to their land for large sums; and if a well opens up, it quickly becomes a gusher of cash. In North Dakota, that has produced a series of so-called High Plains millionaires; for other landowners, leasing fees have become a lifeline for their farm or property.

Private-property rights, often of middle-income people, are the real drivers behind the fracking revolution, with county and state governments leasing rights on their lands not far behind. It’s one reason so many state capitals have been amenable to the fracking revolution: They’ve been prime beneficiaries.

Under the Obama administration, the number of oil- and gas-drilling leases on federal lands has fallen, and oil production on federal lands is at levels lower than in 2007. Nevertheless, America’s oil production jumped by 1 million barrels a day last year thanks to fracking—even as we’re bringing up more natural gas than at any time in our history.

In less than a decade, the boom has already changed the energy map, with the rise of states such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, and North Dakota joining Texas, Oklahoma, and Alaska as major energy producers, and with many others poised to join the club, from Illinois and Wisconsin to Alabama and California.

Indeed, the fracking revolution is the one sector of the Obama economy that’s been steadily booming, creating more than 625,000 jobs in the shale-gas sector alone—a number estimated to grow to 870,000 in 2015. Its benefits also flow in trickle-down savings by lowering the cost of energy, particularly natural gas. Mercator Energy, a Colorado-based energy broker, has calculated it’s saving American families more than $32.5 billion in lower natural-gas bills for home heating and electricity.

It has also had a positive impact on U.S. manufacturing, especially petrochemical and plastics firms that have cashed in on lower natural-gas and oil prices and the increasingly abundant supply. From 2010 to 2012, energy-intensive manufacturers added 196,000 jobs as Rust Belt cities such as Lansing, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana, have been revived by cheaper, more abundant energy.

Wallace Tyner, an economist at Purdue University, estimates that between 2008 and 2035 the fracking revolution (oil and gas combined) will add an average of $473 billion per year to the U.S. economy. That’s roughly 3 percent of today’s GDP.

The most striking change, however, has been at the gas pump. Falling U.S. demand for imported oil (a drop of 40 percent since 2005) has lowered global prices overall, and has been a huge factor in oil’s 25 percent price plunge in 2014. Filling up the family car at $2.80 a gallon versus $3.80 a gallon is a great benefit to Americans, especially in low-income households. A strong case can be made that the shale revolution’s impact on natural-gas prices has been the equivalent of a poverty-relief program, since the nation’s poor on average spend four times more of their incomes on home energy than do the more affluent. On average, the drop in natural-gas prices has given low-income families an effective tax rebate of some $10 billion a year.

This is one of the most notable aspects of the fracking revolution. Unlike the computer and digital revolution, for example, which created an industry dominated by Ph.D.’s and college-trained engineers, this is an economic bonanza of particular meaning to those in the middle- and low-income brackets, with the potential to benefit many more.

Yet today’s liberal left is, virtually without exception, implacably opposed to fracking, from the national to the state to the local level. In the forefront have been environmental lobbying interests. In localities such as Ithaca, New York—the hub of the anti-fracking movement in New York State—liberal elites have banded together to prevent an economic transformation that would pad the wallets of their neighbors and upset the socioeconomic status quo.

Of all the national environmental groups, the Sierra Club probably has the mildest official position: that further fracking in the United States must stop until its overall impact on the environment has been studied more carefully. More typical is Greenpeace’s April 2012 joint statement on fracking (co-signed by the Water and Environment Alliance and Friends of the Earth Europe) that makes a fracking well seem not entirely different from a nuclear-waste dump.

That document asserts that “fracking is a high-risk activity that impacts human health and the wider environment.” It warns that natural-gas development through fracking “could cause contamination of surface and groundwater (including drinking water)” and pollutes both soil and air while it “disrupts the landscape and impacts upon rural and conservation areas.” Greenpeace also claims that fracking and its related activities produce smog, particulates, and toxic methane gas; cause workers to expose themselves to toxic chemicals used in the fracking process; increase “risks of earthquakes”; and lock local communities such as Lycoming County into a “boom and bust economy” that will run out when the oil and gas run out. Greenpeace and its allies insist that these places look to “tourism and agriculture instead.”

The document creates a dire picture, yet nearly every one of these claims is false. Since fracking operates thousands of feet below the aquifer, the risk to drinking water is nil; and there are no proven cases of water supplies becoming contaminated from fracking, despite the thousands of fracking wells drilled both in the United States and Canada. Yet the charge is repeated ad nauseam in anti-fracking ads, films, and pamphlets.

Such is the charge that fracking exposes people, including workers, to dangerous chemicals. More than 99 percent of the fluid used to fracture rock in the operation is nothing more than water and sand mixed together. In fact, most of the statistical risks associated with fracking in terms of contact with dangerous chemicals (benzene is a favorite example, radioactive isotopes another, methane yet another) are no higher, and sometimes lower, than those associated with any other industrial job or outdoor activity, including driving a big-rig truck.

The charge that fracking can leak methane into drinking water stems from a Duke University study that examined a mere 68 water wells in a region of Pennsylvania and New York in which 20,000 water wells are drilled each year—and those who conducted the study never bothered to ask whether any methane concentrations existed before the fracking began (which turned out to be the case).

That fracking might cause earthquakes is another oft-repeated alarmist charge with no facts or evidence behind it. In certain conditions, deep underground injections of water and sand used in fracking can lead to detectable seismic activities, but so can favored green projects such as geothermal-energy exploration or sequestering carbon dioxide underground. None of these adds up to seismic rumblings any human being will notice, let alone an Irving Allen movie-style catastrophe. And given the fact that for years there have been thousands of fracking wells around the country that operate without any detectable seismic activity, the argument seems clearly driven more by the need to generate emotion than the imperative to weigh actual evidence.

But perhaps the oddest claim from groups such as Greenpeace is that increasing the use of natural gas will not reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. The evidence is overwhelmingly the opposite. As natural gas continues to squeeze out coal as a cheap supply of energy, especially for power plants, the greenhouse-gas-emission index will inevitably head downward. In fact, since the shale boom, those emissions in the United States have been cut by almost 20 percent, a number that one would expect to make any environmental activist smile.

All of which suggests that the war on fracking is waged in defiance of facts. And that, in turn, suggests a particular agenda is at work in the anti-fracking camp. A hint of it appears in Greenpeace’s claim that local communities would be better off sticking to “sustainable agriculture and tourism,” meaning organic farming and microbreweries that cater to the tastes of affluent and sophisticated out-of-towners. The war on fracking is a war on economic growth, which the shale revolution has managed to sustain in the middle of the Obama recession, and a war on the upward mobility any industrial revolution like fracking triggers.

It is part of what the Manhattan Institute’s Fred Siegel has called the “liberal revolt against the masses,” and a good place to see it in action is in New York State.

In 2006, then-gubernatorial candidate Eliot Spitzer made a campaign swing through the so-called Southern Tier of upstate New York. The Manhattanite expressed shock at a landscape that was “devastated,” as he put it, and was steadily being abandoned for lack of jobs and economic opportunity. “This is not the New York we dream of,” he said.

Much the same had been true of large portions of rural Pennsylvania. Fracking reversed the downward course there. But the moratorium Spitzer’s successor, Andrew Cuomo, placed on fracking in 2008 before locking it in permanently late last year has frozen those portions of the state in their relative poverty.

Local farmers have been furious over the de facto ban. They are frustrated that the valuable source of income that fracking would generate has been denied them—and that Albany and its liberal enablers are content to crush them under the twin burden of some of the highest property taxes in the country and a regulatory regime that, in Fred Siegel’s words, “makes it hard to eke out a living from small dairy herds.”

Locals are furious, too, that the ban is denying blue-collar jobs that could help young people find work in a fracking site and could transform local standards of living. In 2012, the state’s health department determined that hydro-fracking could be done safely in the state and concluded that “significant adverse impacts on human health are not expected from routine HVHF (hydro-fracking) operations.” This was not what state officials wanted to hear, and the report was buried. When someone leaked it to the New York Times, the Department of Environmental Conservation’s spokesperson quickly disavowed it. Meanwhile, Cuomo’s acting health commissioner, Howard Zucker, served as front man for his boss’s permanent ban.

Ithaca is the center of New York’s anti-fracking hardliners. Their leader is Helen Slottje, who organized the Community Environmental Defense Fund to use local zoning regulations to keep fracking out of the surrounding county. She admits that many local people down the hill from Ithaca resent their efforts and think that she and her environmentalist militia are little more than thieves stealing money from their pockets.

But Slottje dismisses their worries, just as she angrily dismisses the charge that she’s a classic example of someone who opposes salutary change because she doesn’t want it in her own back yard. “If a serial killer knocks on your door,” she says, “it’s not NIMBYism to fight back.” She doesn’t bother to wonder whether her comparison of frackers to serial killers might be slightly exaggerated. She simply adds, “We’re not NIMBY, we’re NIABY. Not In Anyone’s Back Yard.”

She is joined in her activism by the Duncan Hines heiress Adelaide Gomer, whose anti-fracking Park Foundation is based in Ithaca and bankrolls much of the activism. “Hydro-fracking will turn our area into an industrial site,” she has proclaimed. After citing the usual charges about poisoning the aquifer, she also adds, “It will ruin the ambience, the beauty of the region.” The beauty of falling-down barns, rusted cars and farm equipment, and abandoned farmhouses may be lost on the locals, but it’s united the rich and influential in New York City. They want to keep things that way—and keep the “creepy advances of environment-trashing frackers” out of the state.

Gomer was able to mobilize demonstrations around the state to maintain the ban despite lobbying in Albany to overturn it, while celebrities such as Alec Baldwin, Robert de Niro, Yoko Ono, Debra Winger, Carrie Fisher, David Byrne, Jimmy Fallon, Martha Stewart, Lady Gaga, and the Beastie Boys signed an Artists Against Fracking petition. Like other Manhattanites, they have no reason to worry much about low land prices in the Southern Tier—but they do worry about development that would benefit the locals while possibly spoiling the view.

By cloaking their social snobbery in the clothes of the environmentalist movement, New York’s well-heeled have managed to forestall the kind of wealth transfer that fracking has brought to Pennsylvania. Indeed, some like Slottje are hoping to spread the same anti-fracking gospel back across the state line and stop Pennsylvania’s economic boom dead in its tracks.

A similar class divide is a feature of the debate in California. The Golden State has always been a mainstay of American energy production, going back to the 1920s and even as late as the 1960s, when the state ranked second in oil production after Texas. Not coincidentally, that was also the heyday of California’s economic boom and the vast expansion of its state resources, including its university system—the same system that now provides the dubious environmental-impact studies and willing young demonstrators and foot soldiers for the war on fracking.

California is now fourth in oil production in the United States. Its large shale-oil reserves may top 15 billion barrels. The Monterey Shale field runs for 200 miles from Bakersfield to central California and is largely untapped. Opening up the Monterey field could mean as much as $25 billion in revenues for strapped state coffers, according to a study by University of Wyoming’s Tim Considine and Edward Manderson. California’s natural-gas reserves may be four times those in North Dakota’s Bakken range.

There are also studies suggesting that the economic ripple effect of fracking in California could spread $30 billion to $80 billion of additional wealth across the state for every 1 billion barrels of oil production. (California currently produces around 200 million barrels a year.)

Yet the state’s governor, Jerry Brown, and its political establishment have chosen not to listen to the industry or the analysts or the advocates for the unemployed who point to California’s dismal jobless rate, which, at 7.2 percent, is higher than those of Texas (4.9 percent) and North Dakota (2.7 percent). Instead, green activists and Hollywood, not to mention Silicon Valley, are clearly in command.

In April 2013, after considerable political controversy and debate, a federal judge blocked fracking throughout the state. Plaintiffs in the case were the Sierra Club and the Center for Biological Diversity, the organization made famous for protecting the spotted owl in New Mexico and the Upper Northwest. “We’re very excited,” said the Sierra Club’s spokeswoman when the ruling came down. “I’m sure the Champagne is flowing in San Francisco,” she added, since many of the anti-fracking campaign’s wealthy contributors are Silicon Valley millionaires.

The same is true of Hollywood royalty such as David Geffen and Robert Redford, and younger stars like Matt Damon. Damon was the top-billed name in Hollywood’s first anti-fracking movie, 2012’s Promised Land. The movie’s own standing as a fearless piece of populist muckraking was compromised when it turned out that part of Promised Land's financing had come from OPEC member and natural-gas exporter Qatar. Promised Land’s fictional depiction of fracking’s evil is ballasted by the documentaries Gaslands and Gaslands Two, which repeat many of the same myths and misrepresentations about fracking while introducing several more (such as the claim that the evil genius behind fracking is Dick Cheney).

Yet for all their clout, the Hollywood left and environmental activists have been steadily losing ground in Washington, even under Barack Obama. While the Obama EPA has been happy to impose draconian rules on coal carbon emissions for power plants, it has been curiously reluctant to push federal regulation of fracking. It has left the job to the states instead—an almost unique example of the administration’s respect for states rights. Ron Binz, Obama’s nominee to head the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 2013, dismissed natural gas and fracking as “dead-end technology,” touted a federal push to halt the switch from coal to natural gas for power generation, and insisted on conversion to wind and solar power instead.

But Binz changed his tune when he showed up at his confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Energy Committee, declaring natural gas “a very great fuel” and “the near-perfect fuel for the next couple of decades”—and swearing off any effort by FERC to use its regulatory powers to hamper the free flow of gas from pipelines to trading markets, let alone from the fracking wellhead. (Binz won committee approval by one vote.)

Binz is not alone. To the fury of environmentalist groups, the president himself has touted the success of fracking in producing jobs and growth. “America is closer to energy independence than we’ve been in decades,” he announced in his 2014 State of the Union Address. “One of the reasons why is natural gas. If extracted safely, it’s the bridge fuel that can power our economy with less of the carbon pollution that causes climate change.”

The Sierra Club’s executive director Michael Brune had a swift riposte: “Make no mistake,” he said. “Natural gas is a bridge to nowhere”—or at least nowhere green elites want to go.

And so with the Obama administration content to be a noncombatant, the war on fracking has had to wage its fight at the state and local levels, in some states where fracking has already achieved a beachhead and shown its benefits to people’s and state’s bottom lines.

States such as Texas, Wyoming, and Louisiana may seem like lost causes for the anti-fracking left (although citizens’ groups in the liberal university town of Denton, Texas, have recently mobilized to stop local frackers). But Pennsylvania has become an emerging battleground. In 2014, its attorney general filed criminal charges against ExxonMobil for an alleged waste-water spill by its subsidiary XTO Energy, back in 2010—the first criminal charges for activities related to fracking in the Marcellus Shale. This, in spite of the fact that XTO wasn’t responsible for the spill of 57,000 gallons of waste water (which is about three swimming pools’ worth) into a tributary of the Susquehanna; it was the work of a contractor. But XTO had already paid a $100,000 penalty and agreed to pay $20 million to clean it up. ExxonMobil has the deep pockets to fight back, but smaller companies and contractors won’t if suing fracking operations becomes the new legal sport in Pennsylvania.

Anti-frackers also thought they had a shot at stopping the industry in Colorado. The state is one of the wellsprings of environmental activism, after all, with plenty of willing foot soldiers from campuses such as the University of Colorado at Boulder and the University of Denver. But Colorado also sits on one of the biggest shale fields in North America and is one of the top natural-gas states. In 2013, oil and gas contributed $30 billion to Colorado’s economy, in addition to thousands of jobs.

A serious effort to launch an anti-fracking initiative, which would have banned drilling within 2,000 feet of homes and hospitals and given local community councils effective veto power over fracking efforts, ran aground early in 2014. Colorado Democrats realized it could endanger the reelections of Governor John Hickenlooper and Senator Mark Udall. Fracking is popular with Colorado voters, especially working-class voters. They convinced the multimillionaire congressman Jared Polis to set aside his petition drive for the bill just as Hickenlooper and Udall suddenly turned squishy on the fracking issue, to the fury of local environmentalists. (Udall lost; Hickenlooper was reelected.)

For a while, anti-frackers seemed to have more luck in Illinois, which was an important oil producer until its vertical wells dried up in the 1940s. Downstate counties such as Wayne and White have been in economic decline for decades. Fracking the rich, underlying New Albany Shale could revive their fortunes.

Starting in 2011, drillers began leasing more than 500,000 acres of land, with Woolsey Energy investing more than $100 million in setting up wells that could earn as much as 1.3 million dollars per well for landowners. In Clay County, every working well would produce $172,000 in mineral taxes for the state.

That’s when anti-fracking activists began to get nervous. Groups such as Frack Free Illinois, Global Warming Solutions Group of Central Illinois, and Progressive Democrats of Greater Springfield put pressure on the state legislature and its then-governor, Pat Quinn, to intervene. In June 2013, Governor Quinn signed legislation allowing the state’s department of natural resources to write stringent new rules on regulating fracking—rules that opponents hoped and supporters expected would signal the death of fracking in Illinois.

The proposed new rules required 28 separate certifications before a well could open, including a “cumulative impact statement” that would be wide open to public objections. Indeed, every permit was to be subject to extensive public hearings that would let any “adversely affected person” file an objection—and of course allow activist groups to flood the room.

And yet, when the final rules were unveiled in August 2014, activists were shocked to discover that some of them were far less stringent than—and even undercut—the rules Quinn had recommended. Industry groups were equally frustrated by rules they didn’t like, and they fought back. So the department of natural resources went back to the drawing board to start again. But in November, Quinn lost his reelection bid. Fracking hadn’t been a major issue in the campaign except in downstate counties, but the key political stakeholder in the anti-fracking campaign had been voted out of office. The environmentalist movement’s final hope was to block publication of the new rules; if no one knew what the rules were, they couldn’t drill. No luck. At the end of November, an Illinois judge gave the order that the rules were to be published. However stringent those rules may be, the road to fracking in Illinois is open at last.

For activist groups, this was a major defeat and one that will repeat itself if regulators are even minimally honest. When regulatory agencies actually investigate the dire charges made against the industry, most of the charges evaporate under scrutiny. Remaining health and safety matters, such as waste disposal, turn out to be manageable with simple oversight. In the end, this means that the fight to ban fracking outright is steadily turning into a losing battle.

And when politicians and courts decide to quit the field, what’s left for the left? More protests, even civil disobedience. “We will resist this with our bodies, our hearts, and our minds,” one southern Illinois organic farmer told the website Green Progress. “We will block this, we will chain ourselves to trucks.” Or, as some choice lyrics from “Fracking Gasholes” by XOEarth put it: “2,000 big trucks per well/Dusty growling beasts from hell,/For all the critturs that love to live,/Block the roads, or bid farewell.”

While the activists are lying in the road, fracking and its technologies are constantly evolving. Far from rejecting the environmentalists’ demands for more safety and for meeting community standards, companies are constantly adjusting to make their work as clean as possible. Many now employ reusable water for the hydro-fracking process, for example, while cutting back their use of toxic chemicals. Technologies for water-free fracking are already here and will become increasingly widespread in areas where water resources are scarce. That will be another body blow to fracking’s opponents, who like to claim it wastes water needed for human consumption or agriculture.

And we haven’t even begun to explore the possibilities of natural gas. While fracking has yielded record levels of oil production in the United States, those reserves-in-rock are limited. American natural-gas reserves are not. According to a recent Colorado School of Mines study, they amount to 2.3 quadrillion cubic feet of technically recoverable natural gas in the United States, enough to fuel our energy needs for decades—and the constant technological innovations of the industry will make extracting those reserves increasingly cost-efficient.

Already, in 2013, we saw a 41 percent increase in natural-gas production over 2005 levels, more than 40 billion cubic feet a day. As the economy shifts to rely more on natural gas than on coal and petroleum, the positive change won’t be limited to greenhouse-gas emissions. Natural gas will become a ubiquitous fuel source as it gets converted to alternative transportation fuels that have higher octane levels, and lower emissions, than gasoline does.

Beyond that, there are methane hydrates—deep deposits of crystalline natural gas, embedded in large parts of the Arctic permafrost and ocean bottoms. Even when shale oil and gas have eventually run out, technologies to extract methane hydrates will be able to supply almost limitless energy—according to the U.S. Geological Survey, more than all previous discovered oil and gas put together, even while wind and solar are still trying to figure out how to generate power efficiently.

Progressives who believe themselves to be on the side of science and the little guy at the same time are in fact defying both. This is a battle between the partisans of a discredited ideology from the past and those who see the fast-advancing future. As Peter Huber and Mark Mills point out in their book, The Bottomless Well, energy is the fuel of growth and of life itself. The environmentalists’ target is greater than the future prosperity of America’s least fortunate—it’s their survival.