Beyond seeking to avoid arousing the American ba by inducing complacency, China’s strategy is largely intended to respond to the types of threats Chinese leaders believe the United States poses to China. Many U.S. officials—myself included—were late to recognize just how seriously Chinese leaders considered the U.S. “threat” to be; the accumulation of evidence to this effect convinced many, although not all, of us to look at Chinese perceptions differently. China was far less interested in conventional force projection than it was concerned with countering the American threat. The Assassin’s Mace is a key component of this approach.

I was tasked by the Pentagon to study Chinese threat perceptions. Many of my findings were greeted, then and now, with disbelief. Yet these Chinese threat perceptions, which I refer to as China’s “Seven Fears,” reflect the underlying attitudes of Chinese military and political leaders, particularly because those who wrote about these fears did not intend for their writings to shape popular opinion. The Seven Fears are derived solely from internal Chinese military sources; this was no propaganda effort designed to influence public opinion more broadly.

As China’s leaders see it, America has sought to dominate China since at least the time of Abraham Lincoln. I asked my Chinese contacts for evidence of this purported grand American scheme. Several Chinese military and civilian authors handed over a set of books and articles. From these materials, as well as interviews I conducted during six trips to China from 2001 to 2012, I concluded that China’s leaders believe the United States behaves like an ancient Chinese hegemon from the Warring States era. At first, it seemed to me to be illogical, even bizarre, for Chinese leaders to assert that American presidents from John Tyler to Bill Clinton had somehow learned the statecraft axioms of the Warring States and then decided to apply these esoteric concepts to contain China’s growth. This is a radical departure from the reality; in truth, the United States has labored to support China’s sovereignty, to promote Chinese economic development, and to give China a strong place in the global community.

I was astonished that my own report confirmed a revelation that I and others had previously dismissed as implausible even though it came from one of the highest-ranking Chinese defectors. Chen Youwei, a defector from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, identified several pathologies in Beijing’s decision making: reading the worst intentions into an adversary’s actions, ideological ossification, and disconnection from reality. Strangely, the Chinese had presumed that China was at the center of American war planning.

China’s Seven Fears are as follows:

1.) America’s war plan is to blockade China:

The behavior of most strategic actors is influenced by their psychological peculiarities: factors such as emotions, culture, and fears. China seems to fear blockades of its long coastline, and the string of islands off most of its coast makes the leadership feel even more vulnerable. Many in the Chinese military fear that China could be easily blockaded by a foreign power because of the maritime geography of the first island chain stretching from Japan to the Philippines that is perceived to be vulnerable to fortification. The islands are seen as a natural geographical obstacle blocking China’s access to the open ocean. Indeed, a former Japanese naval chief of staff has boasted that Chinese submarines would be unable to slip into the deep waters of the Pacific through the Ryukyu island chain, north or south of Taiwan, or through the Bashi (Luzon) Strait without being detected by U.S. and Japanese antisubmarine forces. Chinese military authors frequently discuss the need for training exercises and a military campaign plan to break out of an island blockade. One operations-research analysis describes seven lines of enemy capabilities that Chinese submarines would have to overcome to break a blockade. The United States, in their estimation, has supposedly built a blockade system of antisubmarine nets, hydroacoustic systems, underwater mines, surface warships, antisubmarine aircraft, submarines, and reconnaissance satellites.

2.) America supports plundering China’s maritime resources:

Chinese authors claim that valuable resources within China’s maritime territorial boundaries are being plundered by foreign powers because of China’s naval weakness, thereby threatening the country’s future development. Various proposals have been advocated to improve the situation. Zhang Wenmu, a former researcher at a Ministry of State Security think tank, goes so far as to say, “The navy is concerned with China’s sea power, and sea power is concerned with China’s future development. As I see it, if a nation lacks sea power, its development has no future.” A 2005 article in the Chinese military journal Military Economic Research states that China’s external-facing economy, foreign trade, and overseas markets all require having a powerful military force as a guarantee.

3.) America may choke off China’s sea lines of communication:

Many Chinese writings touch on the vulnerability of China’s sea lines of communication, especially the petroleum lifeline in the Strait of Malacca. Advocates of a blue-water navy cite the insecurity of China’s energy imports. According to one Chinese observer, the U.S., Japanese, and Indian fleets together “constitute overwhelming pressure on China’s oil supply,” though another study concludes that “only the U.S. has the power and the nerve to blockade China’s oil transport routes.” Similarly, Campaign Theory Study Guide, a 2002 textbook written by scholars at China’s National Defense University, raises several potential scenarios for the interdiction and defense of sea lines of communication. The Science of Campaigns, an important text also published by that university, discusses the defense of sea lines of communication in its 2006 edition. Some authors express urgency: “Regarding the problems . . . of sea embargo or oil lanes being cut off . . . China must . . . ‘repair the house before it rains.’” These advocates seem to want to shift priorities from a submarine-centric navy to one with aircraft carriers as the centerpieces.

4.) America seeks China’s territorial dismemberment:

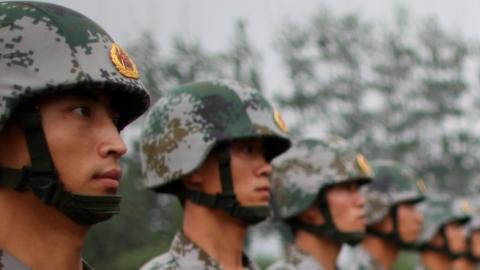

China has outlined campaign plans against various invasion scenarios in a training manual intended only for internal military consumption. An influential 2005 study conducted by researchers from China’s National Defense University, the Academy of Military Science, and other top strategy think tanks assessed the vulnerabilities of each of China’s seven military regions, examining the various routes that an invading force could take. They used the military geography of each region and the frequency of historical invasion by foreign forces to forecast future vulnerabilities to land attack, even identifying neighbors as potential invaders. Recent changes to the structure of the People’s Liberation Army appear to be directed at improving the country’s resistance to land invasion.

5.) America may assist rebels inside China:

The three military regions along the northern border with Russia, including the Beijing military region, are said to be vulnerable to armored attacks and to airborne landings, as expressed in the 2005 study China’s Theater Military Geography. The “Northern Sword” exercise in Inner Mongolia in 2005 involved elements of two armored divisions: more than twenty-eight hundred tanks and other vehicles performed China’s largest field maneuver involving armored troops and an airlift over two thousand kilometers that simulated an attack on terrorists who were receiving foreign military support. Chinese spokesmen claimed the exercise scenario was foreign support of domestic terrorists but did not mention America explicitly.

6.) America may foment riots, civil war or terrorism inside China:

Constant Chinese proclamations against foreign support for “splittists” in Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang have become accepted as part of ordinary Chinese rhetoric, but these statements reflect a deep concern about China’s territorial integrity. A researcher with the Central Party International Liaison Department placed internal threats from splittists and the Falun Gong religious movement on the same level as the threat posed by U.S. hegemony.

7.) America threatens aircraft carrier strikes:

For at least a decade, Chinese military authors have assessed the threats from U.S. aircraft carriers and analyzed how best to counteract them. Operations- research analysis has suggested how Chinese forces should be employed to deal with the vulnerabilities of U.S. aircraft carriers, while other research cites specific weapons systems that China should develop. The Chinese anti-carrier missile is one of the responses to this fear of carrier strikes.