Twenty-five years ago this past Sunday, President George H. W. Bush — in whose administration I served — went before a crowd gathered on the White House’s south lawn and signed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This past week, trustees reported that Social Security’s disability-insurance trust fund is at the edge of insolvency; at some point in 2016 there likely won’t be enough cash to pay all the benefits.

The ADA’s 25th has been much noted, but its relationship to the trust fund’s huge looming insolvency has not.

The future of the disability trust fund was far from anyone’s mind at the signing ceremony. Many were ecstatic about the new law. Most were confident that barriers for disabled Americans would fall.

But no one expected that more Americans with disabilities would be dependent on government 25 years later, but that’s what has happened.

The disability activists who pushed for the new law thought that Americans with disabilities were largely like them: excluded from the mainstream and wanting to get in. They made common cause with the supply-siders in the Bush0administration: The height of a concrete curb at a street corner was as much a barrier to work as high marginal tax rates for those who use a wheelchair. Both tax cuts and curb cuts removed barriers. Both led to growth in the economy. Curb cuts might have some cost associated with them, but they would bring the economic benefit of more people able to work, buy things in stores, and eat in restaurants.

In his inaugural address, President Bush had said, “This is the age of the offered hand.” Both activists and those who faced the burden of complying with the law shared the assumption that those with disabilities would come forward and ask for accommodation. The result would be an America in which those both with and without disabilities could find work and perform at the level of their ability.

Uncertainty tempered applause by representatives of the private-employer community and local government who attended the signing ceremony. The burden of providing the required “reasonable accommodation” would fall largely on them. There was precious little data to support any assessment of how much compliance would cost. The government did not collect data at the detailed level required to say with confidence how many people had impairments that made them covered by the law. The findings section of the new law said that 43 million Americans, more than 17 percent of the population, had disabilities. A lot of people could step forward and ask for something because of the new law.

The broad definition of disability in the law came from self-proclaimed disability activists, whose movement was originally based in identity politics. Earlier groups had brought together people who shared the same impairment: The National Federation of the Blind organized in 1940, the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund in 1979.

Examples raised by skeptics produced the few exceptions in the law to the principle that any impairment that limits a major life activity is a protected disability: The law excludes kleptomania, pyromania, and compulsive gambling, as disabling as those conditions might be.

But no one present at the 1990 signing ceremony anticipated where less stigma surrounding disability might lead. In addition to bringing a marginal group into the mainstream, the law invited those at the margin of disability to claim that status. Changes in attitude and self-perception brought unanticipated costs. The ADA made no change to Social Security, yet there has been a substantial increase in the number of people who saw the offered hand described by President Bush bearing a monthly check.

The number of workers who receive Social Security disability-insurance payments has almost tripled. At the end of 2014, 9 million workers had a disability award that entitled them and their dependents to a monthly government check. This was a 197 percent increase over the 1990 number; over the same period the working-age population had increased by only 29 percent.

The disability path out of the labor market has become much more inviting since the ADA became law. More claims point to pain and other conditions whose diagnoses largely rely on patients’ subjective experiences rather than the self-evident disabilities of those who have appeared in coverage of the ADA’s 25th.

It’s become easier for some Americans with disabilities to join the economic mainstream, but the chances of leaving it have grown for others. Three-quarters of those who have disability-insurance awards have at best a high-school education. Almost to the last, the activists I met in 1990 had college degrees. As in the economy generally, the skilled have done better in the last 25 years.

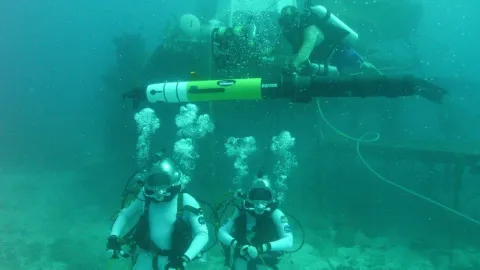

The celebration of the ADA’s 25th will focus on what has happened because of the law itself. The direct effects of the law can be seen whenever one crosses over a curb on a curb cut or enters a public bathroom.

The indirect effects are elsewhere: More Americans now see themselves as so disabled that they apply for disability benefits. This, too, is the legacy of the ADA.