Executive Summary

The United States’ airfields face a threat of severe Chinese military attack. People’s Liberation Army (PLA) strike forces of aircraft, ground-based missile launchers, surface and subsurface vessels, and special forces can attack US aircraft and their supporting systems at airfields globally, including in the continental United States. The US Department of Defense (DoD) has consistently expressed concern regarding threats to airfields in the Indo-Pacific, and military analyses of potential conflicts involving China and the United States demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of US aircraft losses would likely occur on the ground at airfields (and that the losses could be ruinous). But the US military has devoted relatively little attention, and few resources, to countering these threats compared to developing modern aircraft.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) expects airfields to come under heavy attack in a potential conflict and has made major investments to defend, expand, and fortify them.1 Since the early 2010s, the PLA has more than doubled its hardened aircraft shelters (HASs) and unhardened individual aircraft shelters (IASs) at military airfields, giving China more than 3,000 total aircraft shelters—not including civil or commercial airfields. This constitutes enough shelters to house and hide the vast majority of China’s combat aircraft. China has also added 20 runways and more than 40 runway-length taxiways, and increased its ramp area nationwide by almost 75 percent. In fact, by our calculations, the amount of concrete used by China to improve the resilience of its air base network could pave a four-lane interstate highway from Washington, DC, to Chicago. As a result, China now has 134 air bases within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait—airfields that boast more than 650 HASs and almost 2,000 non-hardened IASs.

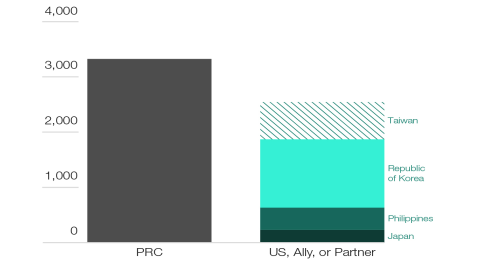

In contrast, US airfield expansion and fortification efforts have been modest compared to US activities during the Cold War—and compared to the contemporary actions of the PRC. Since the early 2010s, examining airfields within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait, and outside of South Korea, the US military has added only two HASs and 41 IASs, one runway and one taxiway, and 17 percent more ramp area. Including ramp area at allied and partner airfields outside Taiwan, combined US, allied, and partner military airfield capacity within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait is roughly one-third of the PRC’s. Without airfields in the Republic of Korea, this ratio drops to one-quarter, and without airfields in the Philippines, it falls further, to 15 percent.

Overall, this creates an imbalance in which PLA forces would need to fire far fewer “shots” to suppress or destroy US, allied, and partner airfields than the converse (see figure 1). This imbalance ranges from approximately 25 percent if the US employed military airfields in Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan to as great as 88 percent if it employed only military airfields in Japan.2 Operationally, this could make air operations in a conflict significantly easier to sustain for the PRC than for the United States; strategically, this destabilizing asymmetry risks incentivizing the PRC to exercise a first-mover advantage. China could initiate a conflict if it sees an opportunity to nullify adversary airpower on the ramp.

Figure 1. Estimated Munitions Required to Neutralize Airfields, by Location

Source: Authors.

The US Department of Defense can organize and resource its forces and infrastructure to sustain air operations while under attack. But to regain an advantage and deter conflict, the United States, as well as allies and partners to varying degrees, should pursue the following three lines of effort.

1. Induce Continued PRC Defensive Investments

The United States should continue to improve its ability to strike PLA forces and key elements of critical infrastructure at depth and en masse despite the presence of dense, unsuppressed air defenses. In response, the already hardened PLA would likely continue to spend funds on additional costly passive and active defense measures and in turn would have less to devote to alternative investments, including strike and other power projection capabilities.

2. Field Resilient Infrastructure

The United States should enhance the resilience of its military infrastructure, including but not limited to expanding the capacity and hardening of airfields in the continental United States, the Indo-Pacific, and beyond. Although funds spent on active and passive defenses detract from funds available for offensive capabilities, without a currently missing baseline level of infrastructure resilience, it is reasonable to expect that the DoD’s offensive capabilities will be suppressed in a conflict. Resilient infrastructure is needed to allow US air forces to fight effectively.

Resilient architectures should include passive defenses (such as redundancy, geographic distribution and tactical dispersal, hardening, reconstitution, and camouflage, concealment, and deception capabilities) and active defenses. As concluded by Christopher Lynch and other analysts of the RAND Corporation, which has conducted the bulk of US analysis on airfield resilience, “the most-cost-effective ways to improve air base resilience are robust, passive defenses.”3

To comprehensively harden airfields, the DoD will need to shift from treating each construction project individually to conducting a campaign of construction.4 A major, multi-year campaign of bundled construction at airfields inside and outside the United States—especially in the Indo-Pacific—would create a sustained push for military construction activities at bases, allow the creation of consortia of commercial contractors, and reduce construction costs. As an element of this campaign, the United States could execute joint contracts with those allies that are also hardening their infrastructure.

Additionally, the DoD should adopt appropriate hardening measures, especially when undertaking new military construction activities. For example, its current plan to forgo the construction of approximately $30 million hardened aircraft shelters for new over-$600 million B-21 bombers is a foolish decision that endangers the US’s ability to strike globally.5 Similarly, in response to a recent spate of likely foreign drones flying over key military bases and installations, the DoD should harden key airfields, including by building HASs.

To sustain operations, airfields will also need protection via active defense designs that are lethal, adaptable, and resilient in the face of continued enemy action.6 This requires the US Army to reallocate funding from maneuver forces to grow the Air Defense Artillery branch and deepen its capacity to defend airfields, ports, and other critical assets. It also requires more, survivable air and missile defense systems and effectors capable of sustaining calibrated, protracted defenses.

3. Evolve the Force

The DoD should develop and accelerate the fielding of forces that are less susceptible to the PLA’s airfield attacks. Elements of this shift in force design should include long-range and -endurance aircraft, such as B-21 bombers and Next-Generation Aerial Refueling System (NGAS) tankers that can operate from more distant airfields or spend more time in the air rather than on the ramp—where they are easier targets. The Pentagon should also deploy forces such as missiles and some types of autonomous collaborative platforms that can operate from short or damaged runways or independently of airfields—if they are logistically supported. However, the US military will not field these types of forces in large numbers until the 2030s, and the DoD will still require passive and active defenses at airfields regardless of these changes in force design. It cannot hope future military forces will address its current airfield weaknesses.

In summary, US airfields face a severe threat of attack. The current DoD approach of largely ignoring this menace invites PRC aggression and risks losing a war. Executing an urgent and effective campaign to enhance the resilience of US airfield operations will require informed decisions and sustained funding. Passive defenses, including hardening, are essential; China, Israel, Russia, Ukraine, and other countries have invested heavily in them to sustain airfield operations amidst attack—as has the United States in the past. It is past time for the United States to do so again.