For decades, the United States has relied on airpower and the qualitative superiority of its aircraft to gain an advantage over its adversaries. But that advantage is rapidly eroding. The Chinese military is fielding sophisticated air defense networks that include robust passive defenses, challenging sensors, and highly capable missiles and aircraft. In fact, by our calculations, the amount of concrete used by China to improve the resilience of its air base network could pave a four-lane highway from Washington, D.C. to Chicago.

China’s strike forces of aircraft, ground-based missile launchers, and special forces can attack U.S. airfields globally. The U.S. Department of Defense has consistently expressed concern regarding threats to airfields, and military analyses of potential conflicts involving China and the United States demonstrate that most U.S. aircraft losses would likely occur on the ground at airfields. Despite these concerns, the U.S. military has devoted relatively little attention to countering these threats compared to its focus on developing modern aircraft.

U.S. airpower concepts have largely assumed that U.S. forces would deploy to forward airfields uncontested and that small-scale forward threats to airfields could be nullified. However, China is capable of mounting large-scale, sustained attacks against U.S. and allied airfields in the Indo-Pacific elsewhere. To generate airpower amid this onslaught, U.S. and allied forces need to devote a radical level of effort to learn how to “fight in the shade.”

This is the subject of our new report for the Hudson Institute. In the report, we make two observations. First, China seems to expect its airfields to come under heavy attack in a potential conflict and has made major investments to defend, expand, and fortify them. Second, American investments have been much smaller in scale and scope. Given the Chinese military’s threat to air bases, the United States needs to both be ready to disperse and undertake an urgent campaign to rapidly harden the bases that it and its allies and partners need to operate from in the event of a conflict with China. America has done so before in the face of other threats. To not do so today invites aggression — and could result in losing a major war.

Dealing with Past Threats

The U.S. Air Force has contended with varying levels and types of threats to its air bases. First, during the 1950s, concerns about the vulnerability of NATO air bases to nuclear attack led to the development of a dispersed operating concept to mitigate damage from nuclear and conventional attacks. Later, during the Vietnam War, aircraft losses due to mortar and rocket attacks prompted the Air Force to initiate the Concrete Sky program — a crash effort to build hardened aircraft shelters at the Air Force’s main operating bases in Vietnam. From 1968 to 1970, the Air Force built 373 such shelters, which it found to be effective in defeating attacks. It also conducted a study of air base vulnerability that prompted the construction of hardened aircraft shelters at air bases in Europe and the Pacific. The United States and its allies built roughly 1,000 by the end of the Cold War, including more than 100 in Japan.

In the first decades after the Cold War, the U.S. Air Force operated in support of U.S. combat operations from locations of relative sanctuary. About a decade into this period, analysts began to recognize that new weapons combining satellite-guided precision, long ranges, and submunitions could provide an otherwise inferior adversary with the means to disrupt or defeat U.S. Air Force combat and airlift operations in a conflict. For example, a 1999 RAND study estimated that — if sufficiently accurate and equipped with submunitions — a single Chinese ballistic missile could damage scores of American fighters parked at standard spacing intervals on an open ramp.

Hardening in the Indo-Pacific

To support of an invasion of Taiwan, open source Chinese publications call for seizing air dominance by using surprise attacks to destroy and paralyze an opponent’s air force on the ground. In recent decades, the Chinese military has been building what appear to be the capabilities to carry this out. China’s air force has developed a large force of cruise-missile-equipped strike aircraft. China’s Rocket Force has acquired over 1,000 medium-range ballistic missiles capable of hitting air bases across Japan and the Philippines, and 500 intermediate-range ballistic missiles capable of reaching Guam and the other Mariana Islands. That strike force — combining long range, precision guidance, and in some cases submunitions — appears to have made real the threat to U.S. air bases that analysts began to talk about years ago.

Analysts have explicitly called out robust passive defenses, such as hardened shelters for aircraft, as “the most cost-effective ways to improve air base resilience.” Unfortunately, Air Force leaders have a mixed record when it comes to base hardening. In 2022, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall voiced support for hardening Air Force bases in the Pacific, but the next year the then-Pacific Air Forces commander said he did not see base hardening as a cost-effective way to respond.

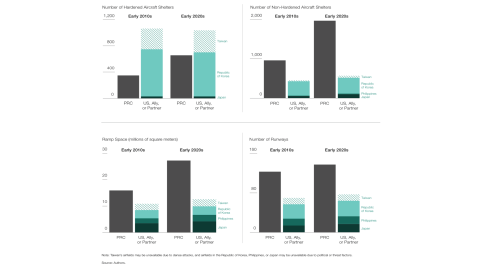

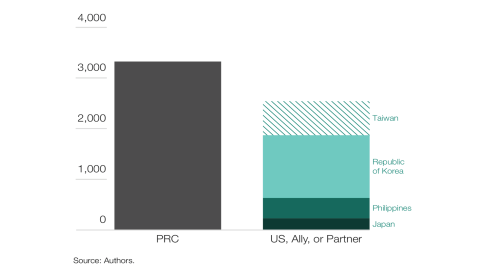

Since the early 2010s, the U.S. military has added only two hardened shelters and 41 non-hardened ones at airfields within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait and outside of South Korea. It also does not appear likely to add any new hardened shelters anytime soon. Including allied airfields outside Taiwan, combined military airfield capacity within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait is roughly one-third of China’s. As can be seen in Figure 1, without airfields in South Korea this ratio drops to one-quarter, and without airfields in the Philippines it falls to 15 percent.

To figure out what China has done to make its air bases resilient, we used commercial satellite imagery to generate estimates of the aggregate improvements to its air bases. In summary, China’s efforts dwarf those of the United States. Entering the 2010s with about 370 hardened shelters, the Chinese military has more than doubled that number, to over 800. The number of non-hardened shelters also more than doubled, giving China a total of more than 3,100 aircraft shelters — enough to shelter the vast majority of its combat aircraft. Over roughly the last decade, China has also added numerous runways and runway-length taxiways, and increased its ramp area nationwide by almost 75 percent. It now has 134 air bases within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait. These bases boast more than 650 hardened shelters and almost 2,000 non-hardened shelters.

Figure 1: Comparison of features at Chinese, U.S., and allied airfields within 1,000 nautical miles of the Taiwan Strait, by location

This has created an imbalance (see Figure 2) in which Chinese forces would need to fire far fewer “shots” to suppress or destroy U.S., allied, and partner airfields than the converse. This imbalance ranges from approximately 25 percent to as great as 88 percent if the United States employed only military airfields in Japan. Strategically, this asymmetry risks incentivizing Beijing to exercise a first-mover advantage — China could strike first if it sees an opportunity to nullify adversary airpower on the ramp.

Figure 2: Estimated munitions required to neutralize airfields, by location

Recommendations

The United States can continue to largely ignore this menace and watch as risk levels increase, or it can face the reality and shape its forces and infrastructure to prevail.

One element of a competitive strategy to gain an advantage is to paradoxically motivate China to double-down on its defensive investment. To do so, the United States should continue improving its ability to strike Chinese forces and key critical infrastructure. By influencing Beijing to spend funds on additional defense measures, Washington can reduce the relative proportion of funds for alternative investments, including strike capabilities.

A strong offense alone, however, will not solve the Defense Department’s problems. Without a baseline level of resilience, it is reasonable to expect U.S. air offensive capabilities will be suppressed in a conflict. Thankfully, the suite of specific improvements is straightforward.

Defend Airfields

First, active defenses are essential to sustained air operations. In the 1980s, amid the threat of Soviet conventional air and ground attacks, the U.S. Army committed itself to “fund, equip, and man ground-based air defenses” as well as air base perimeter defense, for Air Force bases. Those Cold War agreements lapsed in the 1990s and early 2000s, and Army investments in air defense artillery forces have been relatively modest since.

Air base defense is arguably the most important mission the Army could perform in the Indo-Pacific, and Congress should robustly fund the air defense branch. Given competing priorities in the Army budget, this will require accelerating and deepening the Army’s shift of personnel and resources away from ground maneuver forces and toward air defense artillery.

Harden Airfields

Passive defenses are “the most-cost-effective ways to improve air base resilience.” But the military services have spent relatively little on them, which can include not only hardening but also redundancy measures, prepositioning of supplies, reconstitution capabilities, and camouflage, concealment, and deception measures.

To comprehensively harden airfields, the Defense Department will need to shift from treating each construction project individually to conducting a campaign of construction. A major, multi-year campaign of bundled construction at airfields inside and outside the United States — especially in the Indo-Pacific — would create a sustained push for military construction activities at bases, allow the creation of consortia of commercial contractors, and reduce construction costs.

Over the past couple of decades, there has been growing recognition that the U.S. military needs to invest much more in passive airfield defenses. Fiscal limits and a preference for funding other military systems, such as aircraft, have driven a lack of action. Congress could direct the department to rapidly compose a report that assesses the worldwide U.S. demand for airfield resilience measures, including hardened shelters, hardened fuel stores, reconstitution systems, and the like, and to prioritize funding a percentage of the demand each year in its budget submission.

Similarly, Congress could adopt an approach to directly identify and fund these systems. For example, for every new combat aircraft, it will acquire a new personnel bunker, hardened shelter, munitions bunker, or hardened fuel store for an airfield in the United States and another one in the Indo-Pacific. It should also explicitly authorize and appropriate the construction of shelters for high-value aircraft in the United States, such as the B-21, and ensure military construction proposals in the Indo-Pacific account for threats and are hardened. Of note, Congress recently authorized $289 million for hardened aircraft shelters at Andersen Air Force Base in Guam, though the Air Force requested no such funds and it is unclear whether Congress will appropriate those funds.

Absent a major topline budget increase, the Defense Department will need to fund these investments by decreasing spending in other areas, such as reducing funding for the Department of the Army or aircraft procurement. Although reducing aircraft procurement is problematic, modest trades could have outsized positive effects. For example, procuring one fewer B-21 per year over five years could provide enough funding to build 100 hardened shelters in the continental United States, ensuring that in a conflict, Chinese forces will not be able to easily destroy the B-21 fleet in the United States. By buying one fewer F-15EX or F-35A per year, the Defense Department could resource 20 new hardened shelters in the Western Pacific each year.

Evolve the Force

The Defense Department should also accelerate the development and fielding of forces that enable operations that are less susceptible to China’s airfield attacks. This includes long-range aircraft and aircraft and weapons that can operate from short or damaged runways or operate independently of them. However, the U.S. military will not field these types of forces in large numbers until the 2030s, and it will still require active and passive defenses at airfields regardless of these changes in force design.

Counterarguments and Conclusion

Passive defenses may seem at odds with a predominantly expeditionary U.S. approach to warfare. Why spend limited resources on defenses at home and abroad when the U.S. plans on projecting power overseas? However, unless U.S. forces can defend airfields at home and abroad, they will be unable to support U.S. and allied interests in a conflict. As we consider investments in this area, we should be cautious of three seemingly sensible counterarguments.

“Hardening is not cost-effective — instead, rely on dispersal.”

In general, investments in other passive defenses are less costly and have a higher tactical benefit return than hardening. This has led some observers to think hardening is not cost-effective and is unwise. Even though hardening is relatively expensive and, in some cases, may be lower on the priority list of passive defenses, it is highly valuable, and a range of passive defense measures is necessary.

“U.S. forces need only do X.”

Some analyses overestimate the positive impact of single or limited facets of passive defenses, such as runway reconstitution or expeditionary fuel storage. Sustained air combat operations require an interdependent system of systems of personnel, fuel, munitions, maintenance, and other support assets. As it considers investments, the U.S. military will need to holistically enhance the passive defenses of airfields. This may require it to prioritize funding a comprehensive set of improvements to a limited number of locations, rather than attempting to field disjointed improvements to many sites.

“Forget hardening — rather, operate from range.”

Facing major threats to airfields in the Western Pacific, the Department of Defense could forgo fortifying airfields that could come under attack and instead adopt a force design that attempts to operate solely from range. Although the force design of U.S. air forces has become heavily reliant on short-range forces, the strategy of completely retiring from forward airfields has three flaws. First, operative forward airfields can provide three to five times as much capacity on station as distant airfields. Consequently, unless the size of U.S. air forces dramatically increases, they will be necessary to provide appropriate levels of capacity. Second, there is no sanctuary. China will likely be capable in the future of attacking U.S. forces at great distances — even within the continental United States. Third, it takes time to adjust force design. Given current airfield manufacturing timelines, it would likely take more than a decade for the Department of Defense to adopt enough long-range combat aircraft, tankers, and weapons to enable a solely stand-off approach or to adopt sufficient runway-independent capabilities. Such future forces will not solve current airfield challenges, and the ability to operate a major proportion of U.S. aircraft from forward airfields would still be highly valuable.

Executing an effective campaign to enhance the resilience of U.S. airfield operations will require informed decisions to prioritize projects and sustained funding. What is clear, however, is that U.S. airfields do face the threat of attack, and the current approach of largely ignoring this menace invites Chinese aggression and risks losing a war. Passive defenses, including hardening, are essential, and other countries have invested heavily in them to sustain airfield operations amidst attack. It is past time for the United States to do so again.

Read this article, co-authored by Thomas Shugart, in War on the Rocks.