Introduction

In 2018, Australians were shocked by revelations that a Chinese-funded wharf in Luganville, Vanuatu could be converted into a Chinese naval outpost. The plan to do so was subsequently denied by both the Vanuatu and Chinese governments despite Australian national security and intelligence sources insisting that such plans had been discussed by the two countries. Since then, there have been reports of Chinese discussions with Kiribati to upgrade an airstrip that could be used by military vehicles, and most concerningly, a comprehensive security deal signed between China and the Solomon Islands.

Prima facie, these and other agreements with China are sovereign decisions made by democratically elected Pacific Island nations. Indeed, all these island nations are democracies in that elections are held periodically. Ostensibly, and from this perspective, agreements they make with other countries might be against Australian and allied strategic interests, but might not appear to be problematic for those interested more specifically in democracy promotion.

Unfortunately, the situation is not so straightforward. While legitimately elected governments of sovereign nations have the right to make their own decisions, the problem is that Beijing has been deliberately degrading or circumventing liberal norms such as transparency of decision-making and financing arrangements, accountability of institutions, and freedom of information and expression — all pillars of a healthy and robust liberal democratic polity. In some instances, China is actively conspiring with and assisting democratically elected leaders to protect and preserve their position and regime by retarding or delaying normal democratic processes. This is done in return for comprehensive economic agreements with China that have serious security, military, and strategic implications for Australia and partners such as Japan. Australian strategists are justifiably alarmed by these developments. Democracy advocates should also be concerned as the consequences will be a permanent erosion of democratic institutions and practices in some of these Pacific Island nations.

This paper looks at how China is intentionally eroding democratic institutions and practices in some of these countries and what the Australian response has been. It concludes with some recommendations of what additional or different Australian responses should be to both advance its strategic interests on the one hand and protect and advance democracy in these nations on the other.

Enter China…

In an address to the China-Pacific Island Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum in April 2006, then-Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao declared:

“As far as China is concerned, to foster friendship and cooperation with the Pacific Island countries is not a diplomatic expediency. Rather, it is a strategic decision. China has proved and will continue to prove itself to be a sincere, trustworthy and reliable friend and partner of the Pacific Island countries forever…”

One of the primary ways of enhancing influence and relevance in the Pacific Islands is Official Development Assistance (ODA) as it is one of the most aid-dependent regions in the world. ODA is higher in this region than any other on a per capita basis. According to OECD figures, of the top 25 countries in which ODA is the highest as a proportion of GDP, 10 of these are Pacific Islands.

Beijing has allocated significant resources to that end. From a very low base when then Premier Wen delivered the above remarks, China emerged to become the third largest source of ODA in the years from 2008–21. The Lowy Institute’s latest Pacific Aid Map reveals the Pacific Islands received more than $40bn in government aid between 2008 and 2021, with Australia the largest donor (US$17b), followed by China (US$3.9bn), Japan (US$3.5bn) and New Zealand (US$3.2bn).

These figures need to be placed in their proper context. On the one hand, Chinese aid to the South Pacific constitutes less than 0.15 per cent of overall Chinese ODA. None of the top 10 recipients of Chinese ODA are Pacific Islands. Likewise, and with respect to Other Official Flows or OOF (where the grant element is under 25 per cent and the financing is predominantly commercial in nature) Pacific Islands receive a minuscule amount of what China offers to the rest of the world.

Even so, amounts of ODA which are tiny by Chinese standards are significant by Pacific Island standards. For example, from 2008 to 2022, about 23 per cent of ODA to Fiji — the South Pacific’s most populous nation — came from China. During the same period, China was the first or second largest ODA donor to countries such as the Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga, and Vanuatu. Aid as a percentage of GDP in these countries is approximately 15 per cent, 24 per cent, 27 per cent, and 22 per cent respectively. As mentioned, and in a remarkably short period of time, China has gone from being an irrelevant or non-existent aid donor in this region to the most important one after Australia.

Moreover, ODA is not the only Chinese play. Similarly, from an extremely low or non-existent starting point early this century, China has become the first or second largest source of ordinary and concessionary loans to these and other Pacific Island nations.

Solomon Islands case study: Regime capture and democratic backsliding

The Solomon Islands gained international attention in 2022 following revelations of a potentially open-ended security agreement with China that could lead to the gradual establishment of a de facto Chinese naval base in the Pacific country. This was preceded by the Solomons severing its diplomatic ties with Taiwan in September 2019 and switching it to the People’s Republic of China.

The common reason given for the Solomon Islands’ deepening relationship with China is the increase in Chinese trade and investment in the Solomons in recent years. To be sure, in the latest available figures, China received almost 67 per cent of all exports from the Solomons and enjoys a large current account surplus with China (while it has trade deficits with countries such as Australia). There are also accusations of China paying significant bribes to the political leaders and elites of the Solomons.

These reasons offer a plausible explanation for the cosy China-Solomons relationship. But it is not a complete or sufficient one. The Solomons situation is one where Beijing is exacerbating and exploiting growing division and dysfunction within the country, while the Sogavare government is willingly absorbing and internalising Beijing’s strategic messaging for self-interested reasons. In other words, the current government in Honiara is knowingly allowing its liberal democratic institutions and practices to be degraded and corrupted.

Chinese material offerings and non-material strategies are most tempting and effective when leaders of poorly governed countries are in strife and facing serious and growing opposition to their rule — a typical precursor to democratic backsliding. The Solomons has longstanding domestic political fractures. This reached a critical point when Sogavare decided to switch diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China, having only apparently considered one of the four government reports he commissioned to examine the pros and cons of the change. Indeed, on the day the diplomatic switch was announced, the Solomon Times reported that the Central Bank of Solomon Islands raised serious concerns in a paper such as the risk of unsustainable debt, depressed fiscal revenue, and US responses following the recognition of China. These considered concerns were ignored during the consultation period and were excluded from the taskforce report relied upon by Sogavare. Following two years of turmoil, deadly riots began in November 2021 after the government refused to meet protesters from the province of Malaita. Ironically, these riots were quelled with the assistance of troops from Australia, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, and New Zealand. The following month, a parliamentary motion of no-confidence in Sogavare was defeated, allegedly with the assistance of Chinese funds to pay off other MPs — another assault against democratic principles.

The China factor is just one factor sparking these divisions. The country has long been dependent on outside assistance to support a precarious and uneasy calm. For example, the Australian and New Zealand-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) was deployed from 2003 to 2017 to avoid the near collapse of the state and its economy. RAMSI prevented collapse but has not led to improvements in the country’s institutions and economic prospects. The Solomons has the problem of many states dependent on external economic existence: lack of local business experience and skills, poor employment opportunities, over-dependence on unsustainable and low value-added industries such as logging, weak institutions, and poor governance.

The China factor is a relatively recent one. Chinese migrants are dominating the retail sectors, especially in urban areas. With a low capacity to manage its national resources sustainably, Chinese state-owned and private firms are exploiting the mineral, forestry, and fisheries resources of the country with low regard for sustainable or ecological standards.

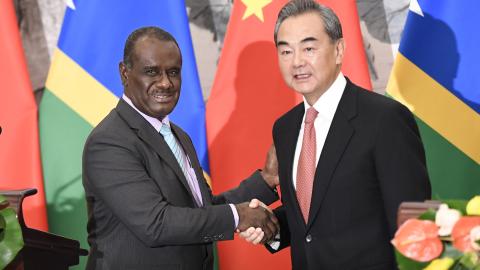

The problem is not Chinese commercial activity per se, but the non-liberal practices associated with ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’ allowed to be imported into the country. For example, Chinese businesspeople commonly bribe their way through government offices to secure licences, work and residential permits, and planning permissions; most of the prime retail sites are occupied or created by Chinese entities; the Chinese-dominated logging industry is characterised by poor environmental practices enabled by the bribery of officials, politicians, and locals; and media and opposition voices are being suppressed. As one illustration, the Media Association of Solomon Islands was forced to boycott the covering of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit in May-June 2022 because of restrictions placed on them by Sogavare at the behest of Beijing. In July, Sogavare announced the government would assume full financial control of the Solomons Islands Broadcasting Corporation (SIBC). Having previously criticised the national broadcaster for giving more airtime to those who oppose the government rather than reporting what Sogavare has been doing, the SIBC will be expected to serve the government rather than operate as an independent profit-making entity under these changes.

This brings one back to Chinese material and non-material approaches that lead to democratic degradation. For example, much of China’s material largesse has been directed towards Honiara rather than provinces such as Malaita, the most populous and one of the most impoverished in the whole of the South Pacific. When the Premier of Malaita, Daniel Suidani, objected to the switch of diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China and subsequently emerged as a leader of the anti-China movement in the country, the Chinese Embassy worked with Sogavare to attack and undermine Suidani. Moreover, the resentment and unrest in the country, which has been exacerbated by Chinese actions, is used by Beijing and Sogavare to justify a deeper security relationship between the two countries. This includes China helping to train Solomon Islands police following anti-China riots and protests.

The point is that as political tensions and divisions in the Solomons become even more fraught, as is likely, the Sogavare government will become even more dependent on comprehensive Chinese assistance to help Sogavare remain in power. The broader point is that China has a modus operandi applied to many weak or poor states with whom it interacts. By supporting and exacerbating a country’s trajectory towards the path of political and social division, economic vulnerability, deteriorating institutions, corruption, and media suppression, the chances of democratic deterioration increase — thereby enhancing Beijing’s importance and leverage over that state. The leader or government then becomes more accepting of and dependent on CCP perspectives and solutions. This has occurred in places such as Cambodia, Laos, Sri Lanka, Maldives, and now the Solomons. Put differently, that country becomes less able to chart its own independent and sovereign course whilst the leader or regime becomes more reliant on Chinese approaches and ways of thinking.

This is where Chinese information and influence warfare comes into play. The growing Chinese presence helps entrench the perception that Chinese pre-eminence in the South Pacific is as inevitable and natural as it is in East Asia. In this context, the BRI branding and framework have been very useful for Beijing. At a 2014 meeting in Fiji between Xi Jinping and the leaders from the then-eight Pacific Island Countries grouping recognising China (rather than Taiwan), Xi urged these leaders to “take a ride on the Chinese ‘express train’ of development.” Following promises of substantial economic opportunities, many South Pacific leaders were delighted that their countries were newly included in the BRI trade corridors.

Although the Solomons did not recognise China until 2019 and was not a part of these interactions, similar messages were being delivered to the Solomons by Chinese state media, its embassy, and Chinese business entities operating in the country during this time. Note that all major Chinese companies operating in the Pacific receive political guidance from Chinese embassies and report to the Economic and Commercial Counsellor’s office. Indeed, the Solomons joined the BRI one month after its diplomatic recognition of China. Sogavare was able to almost immediately announce enormous projects such as the revival of the Gold Ridge in a deal worth reportedly more than US$500 million. The deal was described by Chinese ambassador Xue Bing as an ‘early harvest’ of the new relationship between Beijing and Honiara, from which one is meant to infer that lowering resistance and seeking an opaque and cosy arrangement is the wiser course of action which will lead to prosperity.

The offerings of guaranteed and immediate gains allow another kind of regime capture to which leaders such as Sogavare willingly submit. After RAMSI, the Chinese message is that the Solomons can become more economically vibrant and self-reliant despite its national, institutional, and governance failings — if the Solomons embraces its relationship with China. This is contrasted with the onerous and self-serving demands that Western nations allegedly impose on other countries — and implicitly, on leaders and regimes with different values and standards. Moreover, the Chinese framing is that Western nations want to keep China out of the South Pacific to perpetuate their domination from a bygone era. In contrast, all Beijing wants is a presence to further a friendship with the island nations without demanding the exclusion of other countries.

This framing makes China seem much more reasonable than Australia, Japan, and other allies. It helps to explain why Sogavare dismissed American and Australian concerns with the China-Solomons security deal as “nonsense” while declaring the Solomons had “no intention of pitching into any geopolitical struggle.”

As Chinese Foreign Minister Wang puts it when responding to criticism of Beijing’s relationship with Honiara, “the countries have respected each other, treated each other as equals and supported each other in pursuit of common development.” Additionally, “both sides should be wary of the attempts by a handful of countries, holding onto a Cold War mentality, to interfere in other countries’ internal affairs in the name of human rights…” That Wang’s views were uncritically reported on by the Solomon Times speaks to the extent to which Beijing has been allowed to co-opt or coerce a poorly resourced local media sector into reporting favourably on the bilateral relationship. Beijing has significantly increased its engagement with media in the South Pacific. It offers funding and career opportunities in return for outlets and journalists portraying Chinese actions and intentions in more sympathetic terms. Since Beijing first opened a branch of Xinhua in Suva in 2010, China has funded a growing number of Pacific journalists to attend professional training in China. This included the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Information Department which leads the public presentation of Chinese foreign policy organising formal tours for Pacific Island journalists in 2013 and 2017.

Finally, the extent of regime capture is evident in the way Sogavare praises China and criticises the West. In a speech in parliament, the Solomons leader accused Australia and its allies of undermining his government, criticised the Western response to Russia, and praised China’s treatment of Christians because they were thriving by following the rules set by Beijing. He also suggested civil society groups critical of his closeness with Beijing are being manipulated by outsiders and have “fallen prey to the Western world.” Sogavare called these activists ‘racists’ and ‘bigots’ who are irrationally hostile towards China. He also accused the United States and Australia of threatening the Solomons with ‘invasion’ should there be a Chinese military base.

These arguments are very similar to those offered by Chinese officials and represent targeted disinformation campaigns undertaken by the CCP and PLA, channelled through state-owned and sympathetic media. For example, an opinion piece in the Chinese state-owned Global Times argues that US interference in the South Pacific is the primary cause of instability and tension, while the West treats Pacific Island countries as pawns in seeking to maintain their hegemony and hold back the irresistible rise of China. While China is helping developing countries reach their potential, Western nations remain stuck with a colonial and prejudiced mindset. The notion that the West is threatening the Solomons with military action is a proposition put forward by Beijing.

While those in the liberal democracies tend to treat these views as absurd, conspiratorial, unconvincing, and self-serving, they have important impacts when propagated frequently and relentlessly. In the context of grand narratives about the spectacular and unstoppable rise of China and the largess that comes from that, they offer a ready-made framework for the captured (whether willingly or unwittingly) to explain and justify their actions. In the case of the Solomons, the CCP is offering not just a seemingly attractive economic and security arrangement to an insecure leader and government but a framework and mindset to complement and complete a package deal with illiberal characteristics.

In short, and to offer the Solomon Islands case study some context for this series of reports, island nations are being specifically and persistently targeted by an external Chinese power. They are susceptible due to their heavy dependence on external material assistance. Beijing’s main purpose is to establish China as the benefactor to an ever more reliant government or individual. Some regimes in countries such as the Solomon Islands have succumbed to what is being offered: growing Chinese economic, security and perhaps military presence in return for regime security and largesse. This is the specific challenge we face in advancing democracy in this sub-region.

Australia’s current approach and recommendations

As the leading diplomatic, security, and ODA partner in the Pacific, Australia has a diverse and entrenched set of policies and already makes enormous contributions to the region. For example, in the democracy promotion area, Australia has a long-standing collaborative relationship with relevant institutions in Fiji such as the Fijian Elections Office. Australia supports the Fiji Parliamentary Support Project which assists with improving the ability of Fiji’s parliament to undertake its democratic legislative, oversight, and representative roles. Other activities relevant to democracy promotion include Australia’s multi-year Governance for Economic Program with Samoa which assists with the strengthening of governance and accountability in the country’s institutions. There are similar programs in Tuvalu and Vanuatu. Australia has also offered technical assistance to the Tonga Electoral Commission and provided election observers in Nauru (at the request of Nauru’s Electoral Commission) and Vanuatu.

Indeed, there is not sufficient space in this report to detail the extensive Australian contributions to the Pacific Island nations bilaterally and through peak groupings such as the Pacific Islands Forum.

In addition to assistance which pertains specifically to democracy and electoral matters, Australia is the leading partner in the sub-region when it comes to ODA and other forms of assistance related to improved accountability, transparency, and technical expertise in economic, financial, judicial, administrative, and public sector institutions and practices. Australia also works with peak media bodies and individual media outlets and journalists in countries such as the Solomon Islands, Palau, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Solomon Islands. Australia helped establish and continues to work with the Fijian Press Club to develop free and open media in the country. The most comprehensive assistance is being offered to Papua New Guinea. The two countries signed a Comprehensive Strategic and Economic Partnership in 2020 and a Framework for Closer Security Relations in 2023. The former commits Australia to assist PNG with a wide array of matters covering democratic institutions and systems, accountability in all major government functions, technical economic and infrastructure advice, and ways to strengthen civil society and participation. The latter covers assistance and cooperation in all matters of security including defence, policing, maritime security, cyber, climate change, critical infrastructure, and societal violence.

While Australia remains in a leading and privileged position as the ‘preferred partner’ for many Pacific countries, it has found it more difficult to deal with Chinese elite capture approaches as drawn out by the Solomon Islands case study. It is worth noting that Sogavare consistently reassured Australia that it was his ‘preferred partner’ or ‘partner of choice’ even when the former was agreeing to arrangements with China that were clearly challenging Australian interests. Moreover, it is also clear from the case study that some leaders will prioritise and look more favourably on external assistance that helps them entrench their power and authority over projects that deliver superior and long-term benefits for their economy and society.

Recommendation 1

Countering elite capture via sticks and carrots

Under specific circumstances where China’s use of resources is being used to achieve elite capture (which almost always will lead to a deterioration of democratic standards and degradation of liberal institutions), Australia and other countries should consider ways to either expose such efforts at capture or offer alternatives for that leader being tempted by Chinese largess for this purpose (provided that Australian alternatives meet high ODA or investment standards for quality, benefits and outcomes delivered, and usual standards of accountability and transparency for that project).

This latter suggestion requires a significant mindset shift in the delivery of ODA into these smaller nations. In essence, it involves reframing ODA as part of the strategic toolkit for statecraft to prevent or counter elite capture by countries such as China in these poorer Pacific economies. The intent is still to deliver high-quality and important economic, social, and institutional outcomes for that country. But Australian and allied ODA can be used to increase our attractiveness to the government that we seek to keep on side and dilute the attractiveness of Chinese alternatives. On occasions, it may be that a leader or regime is set on a pathway of accepting Chinese assistance for political advantage at the expense of accountability, transparency, and superior outcomes for the country. In those situations, exposure might be the only counter-response.

Strategic use of resources is already underway in the Pacific Island nations. For example, Australia and other allies have agreed to consortiums to fund undersea cables rather than allow Chinese firms to lay these critical pieces of infrastructure. One such initiative was Australia and the United States partnering with Google and Microsoft to build two trans-Pacific cables to connect Fiji and French Polynesia with cabled Internet that runs from the United States, through to the islands and Australia. Branches will also connect with the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Timor Leste, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. The Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific was set up to provide loan and grant financing to its Pacific Islands partners. One of the implicit motivations for funding infrastructure such as ports, airports, and cables is to counter and offer alternatives to these nations considering Chinese financing for these assets. Inserting a more explicit strategic rationale and democracy promotion element into Australian ODA efforts might seem a giant leap in mindsets associated with the delivery of aid but is not a large advance in terms of existing policy.

Recommendation 2

Supporting independent media and elite capture

One priority ought to be the use of either ODA or other resources to prevent Chinese domination of media platforms and content as is occurring in the Solomon Islands (as outlined earlier). Merely training journalists to reach higher standards of probity and reporting is not sufficient. There needs to be hard dollars devoted to counter Chinese ownership or influence of media environments in these countries — an objective which is not prohibitive from a cost perspective given the small media markets in these nations. This is why a relatively small amount of Chinese money has been able to significantly change the media landscapes in some of these countries.

This should include greater and direct support for independent journalism and to assist the survival of independent media platforms. Notably, the importance of doing so was recently reflected in the 2023 Joint Statement released by the Sunnylands Initiative which brings together experts across the Indo-Pacific to consider challenges to democratic norms and governance in the region. While it is true that merely bombarding a society with state-directed content has not been effective, a compliant local media working in coordination with an increasingly illiberal government is of higher concern.