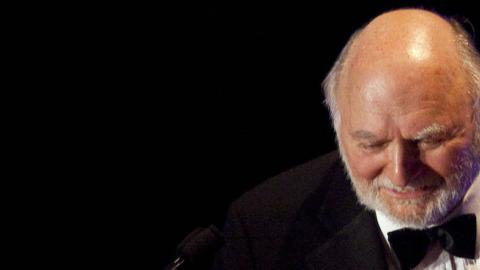

Victor Navasky, the former Editor-in-chief and publisher of The Nation, is having a good year. Nearing his 85th birthday this coming July, and still very active in journalism, the awards are starting to flow in. This year, Harvard University’s Nieman Center, a journalism institution whose mission is “to promote and elevate the standards of journalism,” has given Navasky its appropriately named “I.F. Stone Medal for Journalistic Independence.”

The award, as I explained in these pages some time ago, should more accurately be called an award for overtly biased and often incorrect articles written by prominent left-wing journalists. I.F. Stone was for many years a columnist for small New York City left-wing fellow-traveling newspapers, P.M. and later The Daily Compass. When the latter folded in 1953, Stone started his own newsletter, which he called I.F.Stone’s Weekly (later renamed the Bi-Weekly). Starting with a very small number of subscribers, when he finally closed it down, he had 70,000 subscribers and was writing for mainstream papers and magazines, especially The New York Review of Books. Their editors bought his sub list and made him a Contributing Editor.

But his much-heralded independence and integrity had big holes in it. His most famous story (which started out as articles in the Compass, and then was expanded into a book, The Hidden History of the Korean War) was one in which he unsuccessfully tried to prove that the U.S. started the Korean War; not North Korea, with Stalin’s blessing. His most well-known story turned out to be nothing but conspiracy theory, or as we might call it today, “fake news.” During the Vietnam War, in March of 1965, Stone incorrectly analyzed a famous State Department “White Paper” to try and prove that the South Vietnam Communist NLF was independent of North Vietnamese control. Once again, Stone was wrong.

Stone's sycophancy is now known to have been so blatant that even a reviewer, film critic John Powers, wrote in The Nation (Oct.23,1965) that "Stone's true failing was his tardiness in grasping the full monstrosity of actually existing Communism, especially Stalinism." Stone's "tiger eyes," Powers wrote, "that could spot the threat to liberty in the footnotes of a Congressional report couldn't clearly see the meaning of show trials, slave labor, and class-based mass murder." Powers correctly concluded that Stone, "faced with one of the most tyrannical political regimes of his lifetime, got things so badly wrong that another man might have died questioning his own judgment." And from 1936 to 1939, Stone signed up with Soviet intelligence, in the name of anti-fascism. (You can find the details in Max Holland’s article, “I.F. Stone: Encounters with Soviet Intelligence.” You can also find a complete lengthy evaluation of Stone by me here.)

So, one might say that the Nieman award fits Victor Navasky. “To paraphrase Orwell,” Holland wrote, “Stone’s sin was being anti-fascist without being, for too long, anti-totalitarian.”

One could use these very words to describe Victor Navasky’s set of beliefs. His most well-known book, Naming Names, was perhaps the best example of anti anti-Communism. In it, the blacklisted Hollywood writers were portrayed as heroic victims, rather than as dedicated Stalinists who refused publicly to acknowledge their own beliefs, and pretended instead to simply be “progressives.”

In giving Navasky the award, the Nieman Foundation stated its reasons:

Navasky’s career spans several political eras during which he perfected his own brand of entrepreneurial, independent, nontraditional and courageous truth-telling. Some of his important work, published decades ago, including his coverage of McCarthyism, resonates today with all who have the courage to hold the powerful accountable. At this time, when fact-based journalism is often under attack by powerful political ideologues who label investigative reporting as fake news, honoring Victor Navasky serves as an important reminder that independent journalism that holds powerful institutions accountable is part of a long and necessary tradition in our democracy.

One of the things Navasky is most known for is his continuing insistence that Alger Hiss was falsely convicted and was never a Soviet spy. All the available evidence, which is accepted by virtually everyone who knows anything about this major spy case of the 1950s, accepts Hiss’ guilt. Navasky stands alone with perhaps a dwindling few others, revealing an inability to accept solid evidence when it denigrates a long-standing political narrative he won’t ditch.

To this day, as a long profile of Navasky in the British Guardian suggests, I have been a major critic of his. Over the years, I have debated him at least on three different occasions. The author quotes me at length challenging Navasky’s views of communism and the blacklist, but seeks to undermine it by referring to me- of course- as “the right-wing historian.” Any liberal or leftist reading it knows immediately that he has alerted readers to disregard whatever I have to say. Navasky, as usual, revealed himself to be disingenuous. He tells the interviewer that he was against HUAC’s investigations because he thought “there were [other]ways of exposing the communist apparatus,” as if we are to believe Navasky ever wanted to, or even acknowledged that such a thing as a “communist apparatus” existed.

The past few decades have revealed Navasky to be obsessed not only with Hiss’s would-be innocence, but with resurrecting the old Communists of the 30s through the 50s as heroic martyrs fighting the good fight. Apparently unable to find a publisher, he put out his most recent book as a Kindle single. It’s an attempt to restore the reputation of a relatively unknown African-American Communist, Jack O’Dell, of whom he writes was a man with a “great organizing capacity” and a “brilliant mind…while lamenting what American society, obsessed by the so-called Communist menace, lost by disqualifying him from being an open and visible contributor to the Civil Rights movement.” (my emphasis)

Navasky’s most recent contribution to the continuing attempt to honor old Reds appeared in The Nation on April 6th. His article follows the example of Stephen Cohen, who has made the rounds in print and on TV most recently defending Putin’s regime in Russia and attacking Putin’s critics. The charge of “McCarthyism” is one of the favorite ones used by the left, whose members invoke it regularly to attack anyone who tells the truth about the role played in our past by American Communists. Now, however, Cohen, Navasky and vanden Heuvel are using it as a term for those journalists who criticize Vladimir Putin.

Real McCarthyism, Navasky writes, “involved irresponsible and careless charges of communist affiliation…that to be a Red was to be a subversive…all of which helped create and escalate the anticommunist hysteria.” Hence Navasky condemns the American press and “establishment” of assuming “that the worst charges against Russia (including collaboration with and by Trump) are true,” which he sees as a “legacy of Cold War attitudes towards the Soviet Union.” He alleges that a “cloud of suspicion” hangs over Russia today and Putin because Putin was connected with the former Soviet Union. In other words, Putin is criticized by many in the U.S. not because of what he does as Russia’s leader, but because he is seen as a Soviet communist! Thus Navasky moves into the camp of Trump’s and Putin’s defenders, writing that the media “too easily assume that “Trumpites” who talked to the Russians (even those who then falsely denied it) “are guilty of colluding or collaborating with them,” and he sees them as “victims of the same sort of irrational forces that tainted too many Cold War liberals.”

So foolish is his argument that a few days ago, Nation columnist Katha Pollitt answered him in the magazine’s own pages. Pollitt, who grew up in a leftist family in the 1950s, is no friend to Joe McCarthy’s cause. But she gets the difference between what she sees as state repression then and opposition to Putin today. As Pollitt argues, calling a regular citizen a Communist without evidence could have led to one’s losing a job in the 50s; today a call to investigate Russian hacking and its effects on our electoral process and whether anyone in the Trump campaign had ties to Russia is something else. And the “victims” today are those in power. Trump, after all, “is president of the United States.”

The late Christopher Hitchens, when he quit being a columnist for The Nation in 2002, wrote that the magazine “was an apologist for the failed so-called Soviet experiment, and amazingly still is. When there’s a democratic revolution in Ukraine, [editor] Katrina vanden Heuvel will still say it’s an America-backed attempt to encircle Russia. There’s this instinct to support Moscow…when it comes down to it…[Navasky] will always take a version of that side…he’s quite a hard leftist.” I would add that Navasky's friendly demeanor and affable nature works to mask his very harsh politics.

Were Hitchens still among us, he would be the last to be surprised at the news that Victor Navasky received the Nieman award, or that to learn that Navasky saw attacks on Putin as Red-baiting and attacks on Putin’s regime in Russia the same as an attack on Gorbachev’s regime in the Soviet Union. Or as Pollitt eloquently says it in the ending of her critique:

It’s as if the fact that Russia occupies some of the same geography as the Soviet Union has trapped The Nation in the defensive attitudes of an earlier era. But Russia is not a communist country; it is a capitalist kleptocracy run by an autocrat and an enemy of human rights. If there’s a lingering legacy of McCarthyism around this issue, it doesn’t emanate from liberals but from the left, where some kind of subconscious sympathy with the state formerly known as the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic curiously persists even though the place now embodies everything they oppose.

How refreshing to find one rare sane leftist voice giving it to Victor Navasky in his own magazine.