I had received two degrees in English literature, written a thesis on Dickens, and studied almost every major work of Victorian literature before I thought to read a book by Anthony Trollope. My interest in the great nineteenth-century British novelist was sparked, not by a classroom discussion, but in a casual conversation over cocktails in Hong Kong. It was the early 1980s and Hong Kong was still a British colony. An American banker, visiting from what was then known as Peking, told me about a Trollope craze that had overtaken the American community there. Paperback editions of Trollope's novels were being passed from reader to reader. The usual handover point was the cavernous Peking Hotel, just off Tiananmen Square and home at the time to most of the Americans who were posted to China. I imagined a bleary-eyed banker, up till the wee hours finishing The Way We Live Now, rushing down to breakfast and putting his copy in the hands of the businessman or lawyer or diplomat who was next in line to read it.

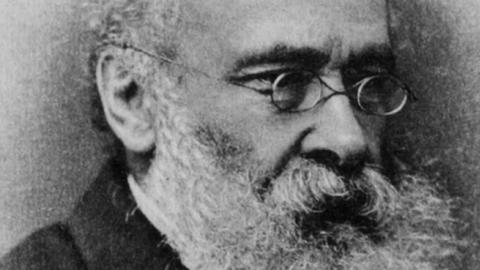

Why would anyone want to read Trollope? I wondered. During his lifetime, his reputation was overshadowed by that of Dickens, Eliot, and Thackeray, who were honored as the great novelists of the day. The Brontes, Hardy, and, of course, Austen, were also up there in the pantheon of notable nineteenth-century writers. Trollope's discipline--he wrote 3,000 words before breakfast--possibly worked against him, creating an impression that he was more of a journeyman than an artist. Since his death in 1882, the academy had mostly pegged him as second-rate. His books were considered entertainment, not literature. He never appeared on any reading list when I was a student.

But the banker's story of Americans devouring Trollope in Peking intrigued me. Not long after our drink, I picked up a copy of The Warden, the first in Trollope's series of novels set in the fictional cathedral town of Barchester. After speeding through the Barchester novels, I moved on to the Palliser series, Trollope's six parliamentary novels. I was enthralled. Trollope's narrative power, along with his astute psychological insights, drew me in to the fictional worlds he created. I came to agree with Virginia Woolf, who said that we believe in the reality of Trollope's characters "as we do in the reality of our weekly bills."

As I later learned, I wasn't the only reader who came late to Trollope. Albert Gordon, the legendary Wall Street investor who died in 2009 at the age of 107, didn't discover the novelist until he was in his sixties. Gordon helped found the Trollope Society in London in 1987 and in New York in 1989. The Society was created for the purpose of publishing all of the writer's output, which includes 47 novels, an autobiography, and numerous short stories and travel literature. Until then, there had never been a complete edition of Trollope's works.

Which brings me to 2015, London, and the series of events taking place this year in celebration of the bicentennial of the author's birth. London is awash in centennials this year--the octocentennial of the signing of the Magna Carta, the bicentennial of the Battle of Waterloo, and centennials of several World War I battles. But the literary event of the year is the Trollope bicentennial.

The British Library has a small exhibit that includes first editions of several books, a note the author wrote to Prime Minister Gladstone begging his pardon for some imagined slight, and an 1834 letter appointing Trollope a junior clerk in the post office. Trollope spent 33 years at the post office, where his most famous accomplishment was introducing the "pillar box"--a stand-alone mail box mounted on an iron post. The Royal Mail issued a stamp in his memory in April, and pillar boxes around town carry bicentennial plaques honoring the author.

Trollope traveled the world for the post office--Ireland, Europe, the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the West Indies. Earlier this year, the Trollope Society arranged for Trollope fans worldwide to launch red balloons in countries Trollope had visited. A label on the balloon told the person who found it how to obtain a free copy of a Trollope book.

On April 24, the anniversary of Trollope's birth, a grand dinner took place at the historic Athenaeum Club on Pall Mall. Former prime minister John Major gave the toast to the Queen. Novelist Margaret Drabble was in attendance, as was actress Susan Hampshire, who played Lady Glencora in the BBC's miniseries of the Palliser novels.

One of the after-dinner speakers was Lord Fellowes of West Stafford--a man better known to the world as Julian Fellowes, creator and writer of Downton Abbey, and a Trollope enthusiast. "I don't want to be impertinent," Fellowes told the audience, "but I feel I have a lot in common with Trollope." He noted that Trollope did not please the intellectuals of his day, who "found him a people-pleasing boor." What "enraged the critics was the popularity of his work." Fellowes spoke of the "nuanced moral characters" that Trollope created. Unlike Dickens, he said, Trollope's "good characters are not all good, and his bad characters are not all bad." Fellowes described how he aspires to make his Downton Abbey characters "Trollopian." Like Trollope, "I want to write about a merciful world--not one divided into good and evil. In Downton Abbey, most of the characters are decent, trying to do their best." Fellowes concluded his remarks with the announcement that he is under contract to write a three-part TV miniseries of Trollope's novel Dr. Thorne.

In this bicentennial year, Trollope's literary standing is higher than ever. The concluding event of the bicentennial celebrations will take place in December in Westminster Abbey, where in 1993, more than 100 years after the author's death, a memorial stone to Trollope was erected in Poet's Corner. At long last, Trollope joined the company of Dickens, Thackeray, Austen, and other greats of English literature.