“To promote common prosperity, we cannot engage in ‘welfarism.’ In the past, high welfare in some populist Latin American countries fostered a group of ‘lazy people’ who got something for nothing. As a result, their national finances were overwhelmed, and these countries fell into the ‘middle income trap’ for a long time. Once welfare benefits go up, they cannot come down. It is unsustainable to engage in ‘welfarism’ that exceeds our capabilities. It will inevitably bring about serious economic and political problems.”

— Xi Jinping

Executive Summary

This policy memo details China’s approach to social welfare and its impact on the nation’s socioeconomic stability. Xi Jinping and other Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders have an aversion to being “welfarist,” which historically aligns with China’s tendency to view its citizens as a source for labor and tax revenue rather than as human resources to be cultivated and assisted when in need. This has resulted in a social safety net that considerably lags international standards, especially those of developed and even middle-income countries.

High debt levels burden Chinese local governments, and shrinking revenues, declining birthrates, falling marriage rates, and aging populations further fuel the deterioration of government finances. These problems contribute to the growing financial vulnerability of Chinese households and create significant concerns for future generations. Families often shoulder the costs of caring for their elderly, educating their children, and paying for healthcare. China’s public healthcare spending is limited, with around 7 percent of gross domestic product devoted to the national system. Families, on average, spend at least 27 percent out-of-pocket of their total health costs to make up for shortfalls in their health insurance, compared to just 11 percent in the United States.

Local governments are responsible for more than 90 percent of China’s social services costs but only receive about 50 percent of tax revenues. For decades, they have relied on land sales and related real estate revenues to meet their budgets, but both sources have declined precipitously as the housing boom has reversed course. According to the Rhodium Group, more than half of Chinese cities face difficulties paying down their debt, or even meeting interest payments, severely limiting their resources for social services. China’s total debt levels are estimated to be around 140 percent of GDP, limiting budget flexibility for supporting social services.

China’s household savings rates are high by global standards, as Chinese increasingly use personal resources to cover shortfalls in the national safety net. As a result, consumer spending and confidence are down. China has seen lower wage growth in recent years, especially in the private sector, reversing the trend of elevated growth in the first part of the 2010s. Through his dual circulation model of growth, Xi Jinping hopes to shift the country away from an export- and investment-driven economy to a consumption-driven model. But the growing burdens on youth and families undermine this shift.

There are major shortfalls in access to, and quality of, education and healthcare systems, especially in rural areas. The hukou system of residency compounds these problems, stopping many rural migrants from obtaining urban residency and thus preventing them from accessing higher quality urban social services.

Due to severe wealth inequality, low tax revenues, and the decision to prioritize resources for national security and investment in manufacturing and technology, Beijing has limited resources to improve social welfare programs. Low public confidence in the economy and consumer market—fueled by the COVID lockdowns—has reinforced falling birth and marriage rates. Youth unemployment and public dissent have also increased, with the so-called lying flat movement and white hair demonstrations exemplifying public rejection of China’s attitudes toward overworking, professional achievement, and CCP handling of elder care and other social services.

Xi and the CCP have chosen to maintain a limited social services system. Their reluctance to improve the system has contributed to a cycle of slowing economic growth, massive debt levels, stressed personal finances, and declining public confidence. China’s ambitions to become a consumption-driven economy will face significant challenges, possibly further straining the implied social contract that has for decades resulted in social and political stability.

Holes in Beijing’s Social Safety Net

Historically, government bodies in China never provided exceptionally generous social benefits to the citizens. So, due to cultural norms and in part to demographic exuberance, traditional Chinese government saw its population more as a source of taxes, soldiers, and forced laborers than as human resources to be cultivated and supported. What analysts today label the social safety net—including healthcare, education, and support for the elderly—traditionally came not from government but instead extended families and local villages. Despite its communist ideology, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has never developed a robust system for these purposes, although it has slowly erected the basic architecture of a modern system.

The two strongmen most responsible for the PRC’s character and institutions, Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping, like the emperors of old, tolerated the exploitation of the Chinese people on a scale foreign to most developed countries. Chairman Mao’s development programs, such as the Great Leap Forward, led to one of the worst famines in history, with more than 45 million lives lost in a few years.1 His drive for building infrastructure such as roads and hydroelectric dams, continued by his successors, displaced millions, irreparably damaged the environment, and led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands and the destruction of untold numbers of temples and villages throughout China.2

As the epigraph suggests, Xi Jinping remains dismissive of the overly generous provision of social services and subventions, and the state institutions and their lack of funding demonstrate his aversion to such services. He has advised the increasingly alienated, educated Chinese youth to “eat bitterness,” as he did in his early years, while they face limited job opportunities with minimal state assistance. Despite the efforts and promise of Xi and his predecessors to eliminate poverty and build a modern economy, investments in the social safety net have lagged far behind international standards.

China now faces a stagnant economy, with GDP per capita less than the global average and less than 20 percent of the US level. As throughout China’s long history, any semblance of social welfare rests in the hands of local governments. But high debt levels and diminishing income from land sales and taxes after the bursting of the real estate bubble imperil their finances. Local governments rely on transfers from Beijing to meet their budgets, and local authorities are responsible for more than 90 percent of the costs of social services while receiving only about half of the country’s tax revenues. According to the Rhodium Group, more than half of Chinese cities have trouble servicing their debt, and many face interest payments that take up more than a third of annual revenues. This severely constrains their ability to finance existing social safety net obligations, let alone improve the system.

Chinese families are thus responsible for making up shortfalls in support for the elderly, education and healthcare systems, and any other crises in everyday life, such as unemployment or support of children unable to find jobs or pay for housing. Families are increasingly hampered by losses in their primary forms of investment (housing and equities), anemic growth in wages and salaries, and the generally high living costs in urban areas. In the early years of Communist China, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and village co-ops began providing much of the people’s social welfare. These institutions now no longer exist or do not have to provide schools, healthcare, and other services. SOEs are further plagued by debt as well as low returns on investments.

Neither local government nor SOEs can consistently find the resources to provide the social welfare benefits common to middle-income countries.

This policy memo provides details regarding the state of social welfare programs in China. It also explains why Xi or his government will likely not correct obvious deficiencies, even as his rhetoric of “common prosperity” promises that the PRC will rely more on personal consumption—which would require an improved social safety net—and less on capital investment, industrial growth, and exports to grow the economy. It concludes with observations on how this self-reinforcing dynamic of stagnation affects contemporary China’s political consensus.

The Weight of Numbers

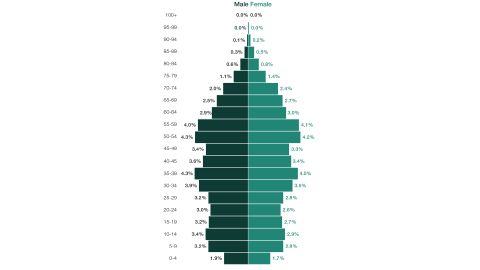

It is well known that China’s huge population is now shrinking and aging. The birth rate, handicapped by the one-child policy in effect for 35 years until 2015, has been on a steady decline. The birth rate remains 60 percent below the replacement rate, reaching actual numbers of around one child per woman of childbearing age. The population’s negative trajectory is not likely to change, and the total population could plummet to around 800 million by the turn of the century. The population pyramid shown in figure 1 illustrates the reality of an aging society with diminishing birth rates. What should appear more like a pyramid is now skewed toward middle-aged groups with falling cohorts of young people, which suggests human constraints on reversing the trend.

Figure 1: China Population Pyramid, 2024

Source: “Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100: China,” Population Pyramid, 2024, https://www.populationpyramid.net/china/2024/.

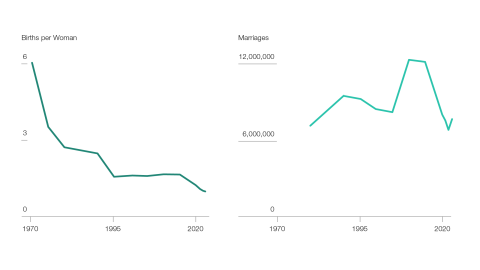

Individual choice explains much of the anemic trendline. Birth rates have dipped over the last six years, with China having 10.478 births per 1,000 people, a 1.57 percent decline from 2023. The number of couples getting married during the first nine months of 2024 was nearly one million less than during that time period in 2023. Figure 2 illustrates the drop in birth and marriage rates over the last decade. According to a Chinese think tank, the relative cost of raising a child in China is among the highest in the world, at 6.3 times the average per capita income to pay for the first 18 years of a child’s life. With Chinese women having a high labor participation rate, the negative career impact on mothers creates another economic disincentive to having children. New mothers experience an average 12–17 percent loss in wages. A 2022 survey of maternity leave among Chinese firms revealed that 63 percent of the survey sample did not offer this benefit. Women traditionally are responsible for the care of elderly parents and in-laws, adding to the difficulties they face in contemplating marriage and childbearing.

Figure 2. China’s Marriage and Fertility Rates Through 2023

Source: Micah McCartney, “China Marriage Data Spells Bad News as Birth Rate Struggles,” Newsweek, November 5, 2024, data from the UN Population Division and the National Bureau of Statistics, https://www.newsweek.com/china-news-marriage-data-bad-news-birth-rate-1980209.

The long decline in birth rates also contributes to the aging of Chinese society and the problems flowing from this development. There are now more than 300 million citizens over the age of 60. Of this cohort, more than 60 percent live alone, and most of them report they cannot afford to live in an elderly care facility, according to a recent official government survey. Those living in rural areas have even less ability to meet their basic needs requirements, a pattern consistent throughout China.

All told, the old age dependency ratio—the number of elderly per employed worker—has grown from around 1:10 in 1950 to 1:2 currently. If current trends persist, it could reach 1:1 by 2100.

The Xi government is surprisingly parsimonious in helping its young and working population to care for both children and their aging parents or other relatives. Young people are already stressed due to high unemployment rates, currently at 17 percent according to Beijing’s data, and stagnant incomes. The falling investment values for traditional stores of wealth, mainly real estate but increasingly equities, compound their problems.

One can legitimately ask what are authorities doing to help young people meet their obligations while trying to build careers. Unfortunately, the PRC childcare assistance program is rudimentary in the most charitable interpretation. An official announcement by the State Council in 2023 noted that “the Chinese government will try hard to perfect its population policies, establish a childcare service system that is accessible to all, and encourage fathers and mothers to share the responsibilities of child-rearing.” It also noted that only 6 percent of children under the age of three have been cared for in nurseries. The official report indicated that the authorities aim to have capacity for 4.5 percent of toddlers by 2025 but added that more than 30 percent of families with young children need nursery care.

Human Capital

Developing human capital is a core requirement of modernizing societies. The average number of years students spend in school in China, at 7.6 years, ranks it 101st out of 150 countries for which credible data exists. In the share of all students completing high school, China ranks 45th out of the 46 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members and partner countries. The ratio of those completing college equivalency is 18.5 percent, ranking it 45th out of 46 OECD members and partner countries. Lastly, only 1.1 percent of the population has an advanced degree compared to 14 percent for all OECD countries and 13 percent for the US.

The clear underperformance of the rural and migrant populations in attaining even rudimentary skills for the modern workforce is a crucial issue. As Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell’s research shows, the lack of schooling in rural areas has had devastating impacts, both in terms of health and the long-term workforce development needed to maintain China’s huge manufacturing and technology economy. According to their on-the-ground and statistical research of rural residents in the hukou system (examined in the next section), who account for 70 percent of all students in 2015, at least half exhibit “delays in cognition, language, or social-emotional skills.” These deficiencies are partly due to inadequate health and living conditions. The authors also project in their best-case scenario that it will be no sooner than 2035 before 42 percent of the entire labor force has reached an “average high school attainment.” For perspective, they observe that “no country has avoided the middle-income trap with high school attainment below 50 percent.” These deficiencies have led most middle-class urban residents to spend heavily on private tutors and other costly forms of assistance to prepare their children for acceptance into elite educational institutions.

Other studies have also shown the poor quality of Chinese education, which suffers because most children are in rural areas or belong to migrant families who cannot send their children to urban schools. A 2015 study measuring reading proficiency found that students in three Chinese provinces came in last among 50 countries, including Colombia, Azerbaijan, and Morocco. A comparative assessment of engineering students concluded that university students in China experienced no improvement in cognitive skills in the first two years of study. Another reported that a sample of Chinese vocational school students suffered a decline in mathematics and made no gains in computing skills during their programs.

The Hukou Stranglehold

Local governments provide social services, and the quality differs widely in China, as discussed earlier for education. Generally, fewer resources are available for social services, and Beijing pays less attention to these issues, leading to poorer quality in rural areas. A major problem for citizens moving from the country to the city—as PRC authorities have encouraged since the days of Chairman Mao—is that rural migrants must often keep their rural status under the hukou residency requirements. Hukou is the classification system the PRC employs to assign urban or specific rural residency status and, with it, an individual’s eligibility to obtain services. Obtaining superior services in urban areas requires going through a sometimes opaque process often administered by corrupt or graft-seeking local officials. In urban China, there are at least 300 million migrant workers who have not obtained urban hukou, and their children typically have the same hukou status, even if born in the city.

The children of rural migrants who haven’t transitioned to urban status cannot attend schools in the cities where they live. Many remain in countryside villages where their parents were born to attend school. In 2020, the number of so-called left-behind children was at least 60 million—these are children whose parents moved to the city for work, leaving them at home. Rural high school graduates receive inferior training and are seven times less likely to attend college and 11 times less likely than urban high school graduates to gain entry to elite colleges.

Migrants face further difficulties because they are paid less than urban hukou workers, and in many cases are not paid for long periods. Data from a dozen years ago showed typical migrant pay at 40 percent less than urban residents. Unemployment insurance is also not generally available for urban migrants.

Additionally, migrants are not eligible for the national poverty assistance program, known as Dibao, and are effectively eliminated from the national pensions system, which requires 15 years of continuous employment to be eligible. Starting in 2030, this minimum of 15 years will gradually rise to 20 years, increasing every six months. Data also shows that less than one-third of those eligible for Dibao relief nationwide manage to get it. In another study, two-thirds of successful recipients were found not legally eligible for benefits. This is yet another sign of graft and corruption, as many relatives of local officials managing the program were among the ineligible beneficiaries.

The system regulating the transition from rural to urban residency remains inflexible for several reasons. Cities are stressed financially and want to avoid the extra costs of providing more people social services like education, pensions, unemployment insurance, and health insurance. Local officials too often treat the application for urban residence as an opportunity for graft and use it as a form of social control and surveillance. These officials also want to encourage wealthy, highly educated individuals to settle in their cities and add to the economy, and frequently deploy point systems heavily weighting education, wealth, and family connections to operationalize their bias. Finally, many rural migrants prefer to maintain their rural land rights, which typically are inherited rights to village common land and farmland where their ancestral home remains. Urban land is not generally available for private ownership, and access to housing is more difficult for non-hukou holders, although this restriction is now changing in some localities. More than a dozen cities in China have introduced plans to give new buyers residency, most notably Guangzhou—the first of China’s “tier-one” cities to do so.

Pensions and Healthcare Fail to Meet Needs

Services to assist cash-strapped families in their growing obligations to their children are substandard, and similar deficiencies beset larger social support programs for elder care. The health care system saddles working-age providers for children and the elderly with often burdensome cash needs because the health care system does not always cover severe illnesses or provide sufficient insurance payments to pay for the cost of services like surgery or advanced imaging.

Because of these deficiencies, working individuals and families throughout the PRC have to increase their savings to make up for shortfalls. Because of excess savings (over 40 percent of GDP goes into savings, as figure 3 shows), consumers lack adequate purchasing power, which creates a negative feedback loop in which lower consumption leads to lower tax receipts (consumption taxes are now roughly 40 percent of China’s total tax revenue). Thus, fewer resources are available to improve social services. Excess savings also weaken the macroeconomy and force the PRC to rely on exports for economic growth.3

Figure 3. China National Savings as a Percent of GDP

Source: Martin Wolf, “China’s Excess Savings Are a Danger,” Financial Times, March 5, 2024, data from the IMF, https://www.ft.com/content/cc40794b-abbb-4677-8a2a-4b10b12b6ff5.

Along with healthcare, the pension system is one of the largest contributors to the squeeze of Chinese people’s finances. The PRC’s old age pension program now covers most people in the country. In principle, a payroll deduction of 8 percent by employees and around 16 percent by employers funds it. Unfortunately, only about one-third of companies were fully compliant with their pension and unemployment funding obligations, according to recent data. Many firms underreport salaries or hire workers on a temporary basis to avoid paying benefits. The pension system is chronically underfunded and undercapitalized, and in recent years, it has required subsidies from the central government to meet current obligations. A National Academy of Sciences study from the PRC estimates that the system would be 10 trillion yuan (roughly $1.4 trillion) in debt by the early 2030s. Even when urban hukou holders can earn and receive a steady pension, the amounts are derisively low, even by Chinese standards. Urban retirees can see about $460 per month, while rural recipients receive roughly $25 per month. To put these numbers in perspective, nursing home care costs around $700 per month in major cities and at least $140 in rural areas.

Unemployment insurance, again financed by payroll taxes, is also underfunded, and strict eligibility requirements make it very difficult to qualify for benefits. Data from 2020 indicated that only 200 million workers were eligible for assistance, and only 2.3 million of the 25 million unemployed at the time received payments. Meanwhile, there were at least 750 million employed workers. This branch of the social welfare system chronically spends more than it receives from payroll taxes, which amount to around 2 percent of salaries. Even at reported unemployment rates of 5.1 percent overall and 17 percent for the 16–24 demographic, the lack of consistent assistance is a major problem.

Minimalist government support for healthcare is likewise a significant problem for Chinese families and an important impediment to any attempt to move the growth model toward domestic consumption—as Xi hopes to do with his dual circulation project. Although a government-run, comprehensive healthcare plan covers most Chinese, levels of coverage do not meet major needs.

The plans are funded by 5–12 percent payroll tax deductions for employers and around 2 percent for employees. There are separate plans for urban and rural hukou holders, with predictable consequences. As mentioned earlier, before the twenty-first century, SOEs or village co-ops provided healthcare coverage, when available, but standard national plans under local government control with direction from Beijing displaced this model. As this policy memo also noted earlier, for pensions and other benefits, SOEs and private employers often neglect to pay into government healthcare plans. Local governments, sometimes with help from the central government, must make up for the shortfall or cut services. The government managers of the system directly pay hospital expenditures, while payroll deduction funding for medicines and outpatient costs pay for individual expenses.

All told, total healthcare expenditures in China only amount to 7 percent of GDP, which is low by international standards. Out-of-pocket expenses for individuals, after accounting for both individual insurance premiums and services not covered by medical plans, amounted to 27 percent of total outlays in recent years, based on official data. In the US, the comparable number is 11 percent. The plan covering rural areas accounts for 73 percent of all Chinese enrolled in the basic healthcare system but receives 39 percent of total funding. Rural participants also receive lower reimbursements for services than those in urban plans. Premiums paid by individuals in this segment of the system have increased by 38 times in the last 20 years, as of 2023, or 20 percent annually. It is perhaps no surprise that the number of subscribers fell by 25 million in 2022 alone. The urban system has the remainder of enrollees but receives more than 60 percent of the funding. Even with more resources, more than 200 million elderly Chinese—particularly among the urban migrants lacking hukou status in cities—have no insurance at all.

Quality indicators also strongly suggest weak outcomes from the Chinese system, especially in rural areas. Rozelle and his colleagues note that rural systems have about half of the doctors and hospital beds that urban jurisdictions have. Overall, China has four intensive care hospital beds per 100,000 people, compared with 38 in the US.

The COVID crisis stressed the system so much that payments to individual accounts were cut nationwide. Government funding for COVID testing was eliminated as the pandemic spread, forcing already debt-stressed local governments to pick up the difference or cut payments to the individual account system. Wuhan, the epicenter of the crisis, cut payments to retiree accounts by 70 percent. Mass protests, even in locked-down residential units in Shanghai and other cities, eventually forced Xi to back down on the lockdown system. The next section will discuss how these developments affected public confidence.

Medical benefits are skewed toward the middle class, government officials, and CCP members. A recent study by two Chinese academics concluded that the special healthcare service accorded to CCP members positively affected their health and economic situations. The “considerably improved” health benefits, in turn, result in “greater resistance to reforms in China’s political system.” Several sociologists have argued that such bias is characteristic of authoritarian states. China expert Yanzhong Huang summarizes the argument in this way:

This is partly because a fragmented and stratified social welfare system hinders horizontal mobilization among societal groups that could pose a threat to regime stability and incentivizes the Chinese middle class to have an increasing stake in supporting the status quo. Looking forward, as economic growth slows and the burden of providing the necessary social services for the elderly mounts, the expansion of the Chinese welfare state is likely reaching its limits.[44]

Emerging Problems with Public Confidence in the PRC and Dissent

This policy memo noted earlier that the Chinese economy is stagnant, and the government is reaching the upper limits of its ability to borrow and invest to stimulate growth. The US and other major importing countries are increasingly resisting trade deficits with the PRC, so Beijing likely cannot rely on exports, especially of goods, to maintain growth. Lower macroeconomic growth and the housing bubble’s collapse also contribute to pessimism that authorities can reverse China’s mounting weakness. Local government budgets are constrained in their ability to improve and pay for the social safety net.

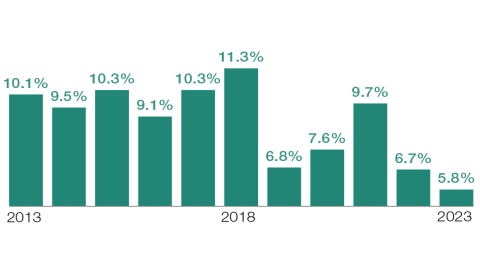

Citizens are frequently and increasingly unable to pay cash for social services not covered by government programs. Figure 4 shows that China’s wage growth has slowed considerably in the last decade. Private sector wage growth lagged that of the public sector, and the growth of the informal sector of the economy creates other difficulties. According to estimates by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, wage growth in the informal sector of the urban economy, with an estimated 200 million workers, is even slower than that of the formal sector.

Figure 4. China Average Yearly Wages Percent Change

Source: “China Average Yearly Wages,” showing percent change, Trading Economics, accessed November 2024, data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, https://tradingeconomics.com/china/wages.

Xi and his predecessors made a series of choices that resulted in the current economic situation, which has seen ever-slowing growth and growing indebtedness for central and local governments. The model largely relies on investment in industry, foreign trade, and national security to the detriment of domestic consumption and the social safety net. As the previous section explored, investment in public welfare lagged and remained well below levels in both industrial and middle-income economies such as Mexico. For years, the International Monetary Fund and many Western economists have urged China’s leaders to shift resources toward reducing debt and supporting domestic consumption as a more sustainable growth model.

The Rhodium Group has convincingly argued that China’s high debt levels substantially diminish the government’s ability to incur fiscal deficits, especially at the local level. The organization’s work suggests total debt levels as high as 140 percent of GDP have historically resulted in severe economic problems. This is undoubtedly one reason why China’s leaders have not been able to deploy the same levels of fiscal stimulus as in recent years, such as during the Great Recession, the 2015 real estate crisis, or the post-COVID recovery.

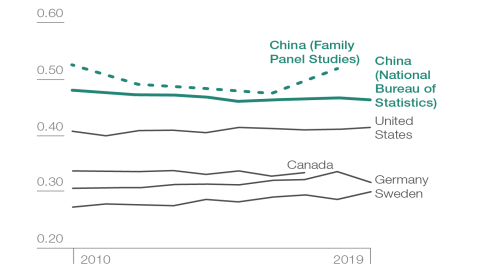

Another sign of weakness is a recent suspension of wages by local governments. According to Hong Kong–based nonprofit China Labour Bulletin, there have been around 1,200 protests over unpaid wages or other compensation-related incidents so far in China this year, following more than 1,600 protests of this nature in 2023. China could conceivably increase taxes, which are 14 percent of GDP—low relative to global averages—to address the shortfalls. Figure 5 illustrates that individual income taxes only represent 7 percent of total revenues, and corporate taxes represent 19 percent while consumption taxes are nearly 40 percent. Nonetheless, Xi appears reluctant to increase taxes on the wealthy, government officials, and SOE officials who generally support his leadership. One result of this regressive tax system is that it maintains a high level of inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient. Figure 6 shows a few measures of Chinese and comparative country Gini coefficients.

Figure 5. China’s 2023 General Public Budget

Source: Brian Hart et al., “Making Sense of China’s Government Budget,” China Power, Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 14, 2024, https://chinapower.csis.org/making-sense-of-chinas-government-budget/.

Figure 6. Comparison of Gini Coefficient Estimates

Source: Ilaria Mazzocco, “How Inequality Is Undermining China’s Prosperity,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 26, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-inequality-undermining-chinas-prosperity.

China’s tax system thus does little to assist its citizens, apart from the wealthy, to meet their growing burdens in paying for the high costs of healthcare, education, and childcare, let alone support the care of aging family members. A major question is whether the tightening vise of obligations leads to a lack of confidence and political discontent when people lack the resources to pay for basic needs. Evidence of declining confidence in the future affects popular views of Chinese leadership and can suggest growing challenges to the implicit social compact in Communist China.

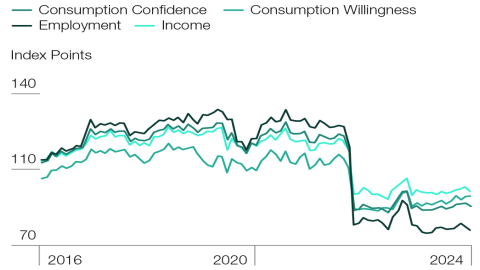

Surprisingly, the starkest evidence of public confidence problems is in official government surveys of confidence. Figure 7 shows a remarkable collapse in several measures of confidence during the darkest period of the COVID crisis and continuing to the present. The precipitous drop in all indicators dates to March and April of 2022, coinciding with the widely publicized and feared Shanghai lockdowns. As mentioned earlier, healthcare benefits were cut, and inhabitants of entire neighborhoods were locked into their apartments. Widespread protests in Shanghai and other major cities eventually resulted in authorities reconsidering their drastic actions. Some of these protests expanded into broader pushback against inadequate services and even reductions in other benefits for the elderly, especially pensions, in what some have called a “white hair movement.” Loss of down payments and slow delivery of prepaid housing also contributed to this protest movement. But the blow to public confidence has persisted into 2024.

Figure 7. Consumer Confidence in China

Source: Logan Wright, Camille Boullenois, Charles Austin Jordan, Endeavour Tian, and Rogan Quinn, No Quick Fixes: China’s Long-Term Consumption Growth (Rhodium Group, July 2024), 10, data from the National Bureau of Statistics, https://rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/.

Few reliable resources provide comprehensive data over time for incidents of dissent in China. The PRC’s demonstrated ability to find and eliminate web posts reporting incidents of protest continues to improve, although diligent observers can find them before the censors remove the evidence. So analysts have to rely on anecdotal reports of movements or individual actions, which provide some insight. Freedom House has a China Dissent Monitor, which is one of the best sources but is not comprehensive enough to inspire confidence except for directional change. Begun in 2022, its data show a doubling of recorded events over the next year, but at some 250 per month, the scope is insufficient to draw definitive conclusions. The China Dissent Monitor recently reported that the 2024 third quarter had a 27 percent year-on-year increase in dissent events compared to the same time period in 2023.

Anecdotally, however, observers can see developments like the white hair movement, the lying flat phenomenon, and full-time children living at home among China’s youth, which are distinct indications of dissatisfaction or even resignation. When put in the context of the high youth unemployment rate, one scholar estimated that 40 percent of the 16–24 demographic had given up or rejected an ambitious, active lifestyle characteristic of the earlier generation. Some demographic data reviewed earlier, such as low birth and marriage rates, strongly suggest that a substantial portion of Chinese youth have a negative outlook on the future.

The government has not given those who have grievances a real avenue to express or resolve them. In addition to the prevalence of web censorship, a 2013 study reported that authorities reviewed and addressed less than 1 percent of petitions to the Offices of Letters and Visits.

A longitudinal public opinion survey conducted by Harvard’s Ash Center from 2003 to 2016 revealed generally high levels of satisfaction (up to 95 percent) with Beijing’s central government, but a dismal 11 percent were “highly satisfied” with local governments, which provide most services.

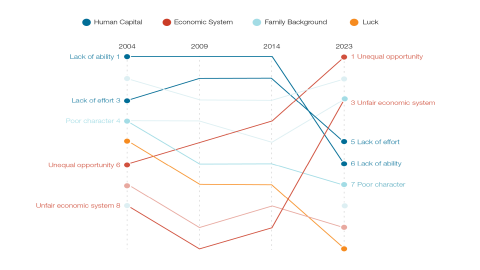

Research by Scott Rozelle, Martin Whyte, and Michael Alinsky revealed a remarkable shift over the past two decades in public attitudes toward the politico-economic system in China. In a series of four surveys starting in 2004, the researchers asked what economic conditions or personal attributes individuals would credit for success or failure in modern China. Results uncovered a significant change after 2014, which provides insight into how respondents view their government, or at least the system it provides for individual fulfillment.4 Figure 8 shows that through 2014 at least, the Chinese largely blamed individual characteristics—“lack of ability,” “lack of effort,” or “poor attitude”—for people being poor in China. Respondents listed structural factors, such as an “unfair economic system” or “unequal opportunity,” as less significant reasons for being poor in China. Between 2014 and 2023, their attitudes reversed, with individual characteristics becoming less determinant than economic structures in explaining personal outcomes, symbolized as being rich or poor. Family background remained important throughout the surveys as a causal factor, which could be interpreted in different ways.

Figure 8. Attribution of Why People in China Are Poor

Source: Ilaria Mazzocco and Scott Kennedy, Is It Me or the Economic System? Changing Evaluations of Inequality in China (Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2024),https://bigdatachina.csis.org/is-it-me-or-the-economic-system-changing-evaluations-of-inequality-in-china/; data from Michael Alisky, Scott Rozelle, and Martin King Whyte, “Getting Ahead in Today’s China: From Optimism to Pessimism,” China Journal 92 (July 2024), https://doi.org/10.1086/733178.

Conclusion

Xi Jinping and the CCP will likely be unable or unwilling to improve the relatively low quantity and quality of services vital to an effective social safety net in China. Xi conflates the increase of such services with a low-performing welfare society, which cultivates weak or listless individuals and saps the nation’s vitality. The dangers presented by the economic slowdown in China, high levels of debt, and a rigid economic model that is resistant to change will also make any changes to the social welfare system challenging. Established and well-cared-for elites also resist changes to the system. The ensuing stasis adds to the already heavy burdens of individuals struggling to meet their family obligations, advance their careers, or more generally pursue personal fulfillment. The failure to improve the social safety net also undermines any transition to Xi’s newest dream of shared prosperity in a dual circulation system that would propel future economic growth and national strength. The resulting stagnation saps economic dynamism and people’s confidence in their government and future. Resigned youth cohorts, desperate older citizens, and various forms of protest are the results and will tend to weaken the social contract in China even further.

*The authors acknowledge the excellent research assistance of Elsa Sophia Zhou for this paper.