The Battle for the Black Sea Is Not Over

Senior Fellow, Center on Europe and Eurasia

Matthew Boyse is a senior fellow with Hudson Institute’s Center on Europe and Eurasia.

CEO, New Strategy Center, Bucharest

Senior Fellow, New Strategy Center, Bucharest

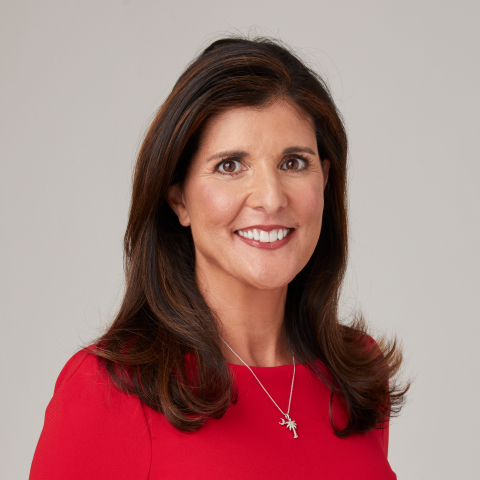

Senior Fellow, Center on Europe and Eurasia

Luke Coffey is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute. His work analyzes national security and foreign policy, with a focus on Europe, Eurasia, NATO, and transatlantic relations.

As Russia scores localized gains on land, Ukrainian forces have achieved major successes in the Black Sea Region (BSR). The Ukrainians have sunk or damaged some one-third of the Black Sea Fleet, forced Moscow to move naval assets away from occupied Crimea, and put Russia on the defensive. These successes challenge the narrative that Russia’s war against Ukraine is a stalemate and demonstrate Ukraine’s determination to preserve its identity, sovereignty, and independence.

Ukraine’s gains are real and strategically significant, but the Battle for the Black Sea is not over. Major Russian land, sea, and air assets remain in Crimea and in the BSR, and Moscow is using them to continue its quest to subordinate Ukraine. The war will be won or lost on land and in the air.

If Russia wins or ends the war on its terms, the interests of all Black Sea littoral states will be negatively affected. But so too will those of the United States, Europe, and the West more broadly. The US has a major interest in a free and open Black Sea and a peaceful, stable, and prosperous BSR.

Join Hudson for an event to present the results of an in-depth study written by a US–Romanian–Ukrainian team: Hudson Senior Fellow Matt Boyse, New Strategy Center CEO George Scutaru, New Strategy Center Senior Fellow Dr. Antonia Colibasanu, and New Geopolitics Research Network Director Mykhailo Samus.

Read the study, The Battle for the Black Sea Is Not Over, here.

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

John Walters:

Good morning. I’m John Walters, president and CEO of Hudson Institute. On behalf of all my colleagues here and our board chair Sarah Stern, welcome to Hudson, and to this event with this distinguished panel. Also want to welcome al those who are joining us virtually. We appreciate the fact that we can have a larger audience, and we hope that more people understand the work that’s going to be discussed here today.

The Black Sea has been much in the news lately. It is a dynamic theater in Russia’s war against Ukraine. While Russia has been advancing on land extremely slowly and at vast cost to human and material, it has been retreating in the Black Sea. As you know, this region is key to not only, the Black Sea, to the war in Ukraine, but to the many nations in the entire region. It has been dominated by Russia since it took Crimea and eastern Donbass in 2014. At that time, millions of people were closely watching developments, and subsequently have seen that the land domain in Ukraine has been the focus of attention. But it should also be a focus of attention, the maritime domaine, in and around Ukraine. Because, as I said, the Black Sea and the Black Sea region is decisive to not only the region, but to trade that goes beyond the region and affects the world.

Today I have the pleasure of introducing Hudson’s latest study, a joint effort between Americans, Romanians, and Ukrainians entitled the Battle for the Black Sea Is Not Over. Hudson is pleased to have partnered with a great team of experts from Romania; Romania’s leading think tank, the New Strategy Center; and the New Geopolitics Research Center in Ukraine. And guiding us through this event is Hudson’s very own Luke Coffey, who needs no introduction and who has himself written extensively on the Black Sea and issues of the region, and the War in Ukraine in the past. It’s my job not to stand between you and the experts, so I’m going to turn the floor over to Luke.

Luke Coffey:

Thanks, John. Thank you, John, for those introductory remarks, and I want to echo John’s thanks to those who came out in person today for this event, and for those viewing online, for this very timely and important launch of a fantastically researched and detailed report entitled, “The Battle for the Black Sea Is Not Over.” The Black Sea probably doesn’t get the focus and attention it deserves here in the US, certainly in the US, but I think it’s probably the same amongst other capitals, certainly in Western Europe.

One way to remedy this, in my opinion, is to, when you look at a map of Europe, have the Black Sea in the middle and then look at everything that’s around the Black Sea. Often as schoolkids growing up, at least certainly for me in the ‘80s and ‘90s, when you had a map of Europe, the Black Sea was the bottom right-hand corner and then it only showed part of the Black Sea. So you never really got an appreciation of the geography.

Another way to do it, and a more detailed and thorough way of understanding the importance of the Black Sea is to read a 100-page report like we have today that lists everything that needs to be done, by chapter and verse. And that’s what we’re here today doing is launching this report. I’m going to quickly introduce the speakers and then they will speak, offering some opening remarks in the order that I introduce them, and then I will facilitate a discussion afterwards.

The first speaker today is Matt Boyse. He is my colleague here at Hudson, a senior fellow in the Europe Center here, and had a very distinguished career in the US State Department. He’ll be followed by George Scutaru, who’s the CEO of the New Strategy Center, based in Bucharest, as John said, the finest think tank in Romania. He will be followed by his colleague Antonia Colibasanu, who is a senior fellow at the New Strategy Center in Bucharest. And then we should also mention another important author for this report, who couldn’t make it today, and that’s Mykhailo Samus, who is based in Ukraine, and he is with the New Geopolitics Research Network, and he’s the director of that institute. So I will turn it over to my colleague Matt for some opening remarks, and then we’ll go to George and Antonia.

Matthew Boyse:

Thank you, Luke, and thank you, everyone. Thank you, George and Antonia for joining us and Mykhailo for joining us remotely. So you might ask, “Well, why another Black Sea report?” Because the Black Sea is actually kind of a hot topic. I mean, yesterday there was a major conference in Sofia on this very subject, and the Secretary of State of the United States actually spoke to the conference. Today, this afternoon, there’s another conference at George Washington University on Georgia and the Black Sea. So if you start looking around, there’s an awful lot that’s been written, so why another one?

And I don’t want to repeat the sort of old German joke about, everything has been said, but not by us. But actually, there is, [foreign language] it’s more a question of, we actually think we have something interesting and new to say here, which is the reason . . . is we were in Bucharest last summer, and George and I were talking about this, and we were identifying what was not being talked about as far as the Black Sea was concerned.

First of all, this whole question of militarization. Now, of course, we know after 2014, and the illegal annexation of Crimea, the whole geopolitical situation in the Black Sea region changed. But had anybody really gone through the whole question of militarization, all the details? The concept was relatively well-understood, but had anybody gone through all these details? And you can read all about it in gory detail, which . . . Wait a second, where’s our slide? Ah, there we go, yeah. If you just download the QR code, you can see this study here. Unfortunately it’s 100 pages, because it goes into enormous detail, but there is an executive summary that’s much shorter, so if you don’t have the patience to read it all.

So we go through this whole question of exactly how was the Black Sea militarized, and what Russian assets are now on Crimea, for example, which our Ukrainian colleague was responsible for putting all this together. So you have this militarization of the Black Sea issue, and also the geopolitical changes that accompany all this. And it has basically turned the Black Sea, that old Greek phrase about [Greek 00:07:47] or inhospitable sea. Because it used to be, I mean, until 2014, the Black Sea was fairly free and open in terms of, ships would fly and all this sort of stuff. It wasn’t as militarized as it is now. And so you had this, I mean, the Russians were obviously interfering in Ukraine, they were interfering in Georgia, they were interfering in Moldova. So there was malign Russian activity, but the maritime domain was relatively free and open until 2014. So the whole geopolitical situation changed.

And then we started encountering these two narratives, and narrative number one was the extent to which Black Sea was turning into a Russian lake, quote-unquote, or not, and then this whole question more recently, beginning mostly last fall, was along the lines of is Ukraine winning the Battle of the Black Sea? Which of course is a true statement in terms of the maritime domain. I mean, if you look at the data, 30 percent of the Russian Black Sea fleet, which is either destroyed, or damaged, or has moved away from the western part of the Black Sea and has moved to Novorossiysk et cetera, and it’s no longer finein areas it used to fine. So you have these two narratives, we’re going to discuss those two narratives.

And then sort of the other idea was to remind the policy community of the other side of the coin, which is that narrative is, Ukraine is winning the sea domain, and the maritime domain, but there’s a lot of Russian assets left on Crimea, and an awful lot of maritime assets, and air, and et cetera, as it’s left that people also need to remember. And then you also have this whole question of sort of spelling out the geopolitical significance of what happens if Russia were to win the war? Because this is actually negative for all the Black Sea electoral states, it would be negative for NATO, and of course, it has implications for the United States, so to remind people of that.

And then, of course, to remind people, again, that Putin moves not only when the West shows weakness, but also when the West shows neglect. And unfortunately, what Luke was saying about the Black Sea being in the lower right-hand corner of a lot of people’s mental map was also present for quite some time, and which was yet another one of the sort of data points that caused Putin to think, “Okay, people are not really focusing on this area, and I can . . . It’s maybe more of a green light.” And then of course last fall we had this question that the assistant secretary of state presented his Black Sea strategy to the Congress. It was a State Department-only document, we have the fuller whole of government, this document is supposed to be blessed this year, and so we wanted to also kind of weigh in on that as well, and then we also, we’re presenting an action plan.

And so these were sort of the concepts behind why yet another . . . “Don’t we have enough Black Sea security studies already?” Well, no we don’t, because some of these issues were not covered, or it’s important to continue sort of updating this as time marches on. The three main takeaways are basically, number one, the battle for the Black Sea, because, look, you’ve written on this, and a lot of people have written on it on what’s happening in the maritime domain, which of course is all totally, completely accurate. But we wanted to basically draw sort of a connection between the maritime domain and the land domain and the air domain. And then the conclusion was, basically, that the battle for the Black Sea is not over, however well things are going on the maritime domain, but the other two domains are going to be very important as well. So it’s not over.

Number two, as Ukraine goes, so goes the Black Sea region as a whole. Because if, for example, Russia were to consolidate its control over the northern littoral of the Black Sea, and of course, prevail in its war against Ukraine, this would have very significant geopolitical consequences, not only for the littoral states, but also for NATO, and, of course, for the United States as well. And then you have the third point being, and this is also an important point, by a former ambassador of Bulgaria to Washington, who once, in a conversation with me, said, “What happens in the Black Sea does not stay in the Black Sea.” And so that being the third kind of takeaway from this.

So these were sort of why we did this in the first place. Maybe I’ll just stop here and we can go into some of the conclusions a little bit later.

Luke Coffey:

Yeah, great. Thanks, Matt. George?

George Scutaru:

Thank you very much. First of all, I want to express my deep gratitude to Matt, to Peter Rough, and the Hudson team, for this cooperation. Also to [inaudible] Group, because [inaudible] supports this study and New Strategy work. And also I say hello to my dear friend Mykhailo Samus, he is in Kiev now, he’s our nonresident expert and director of New Geopolitics Research Networks.

Why the Black Sea matters, I think this is the main question. And it’s necessary to understand that Black Sea means connectivity. It is between, middle corridor in Europe. Three Seas Initiative, and Black Sea is the core, the middle of this initiative. It is the connective with the Balkans, Middle East, North Africa. Black Sea represents a platform for Russia to project its interests to Middle East, North Africa, to Balkans. And also, Black Sea means energy. A lot of transit routes, but also Black Sea has enormous oil resources. And by the way, Romania will become, in 2027, the largest gas producer in EU, and will have capacity to cut this Russian malign influence in the regional countries, providing other gas not from Russia.

But also, Black Sea means a battlefield for Russian hybrid activities. And if you have a large-scale invasion in Ukraine at the same time you have a large scale hybrid warfare against Republic of Moldova from Russian side. And also, we have in the Black Sea a new dangers to freedom of navigation. Mines, electronic warfare activities, they’re trying to jamming communication and signals of vessels. And also, Black Sea means food securities for global world, because Russia, Ukraine, and Romania are providing cereals, grain, to many African and Asian countries, and for instance show some stability with Egypt depends on the grain provided from this region.

But when we are speaking about Black Sea, we’re thinking about the War in Ukraine. And I know that a lot of people even now in DC consider that, okay, it’s better to froze the conflict. Please have in mind that this conflict represents the second episode of a war started in 2014 with annexation of Crimea. And after the annexation of Crimea we had a break during eight years, and Putin restart the war. And this ceasefire or this conflict frozen, will not be a peace for long years. Because Putin will come back. Putin wants to destroy Ukraine, and first of all, it’s necessary to understand that if he wants to destroy Ukraine, first of all, he wants to cut the exit of Ukraine to the sea, and to occupy entirely throughout. And for Romania, this is the biggest nightmare, to see again Russia on our border, on the Danube mouth, and even on the Prut River. Because I’m pretty sure that Russia will occupy Republic of Moldova if they have possibility to enter and to occupy Odessa.

And for us, it’s important for us to have a freedom, independent Ukraine, and to support Ukraine to resist, to hold the line. And by the way, dear friends, today, it’s very difficult for them to resist. Even they are so brave and courageous, it’s impossible to resist without ammunitions. They are spending now less than 2000 round of ammunitions per day comparing to Russians’ 10,000 per day. And they are suffering, they are dying, because we can’t ensure them enough ammunitions, enough weaponaries, and please have in mind that this pressure, it’s increasing, increasing, day by day from Russian side. And if Ukrainian front will collapse, we’ll see Russia on the border of Romania. Russia will occupy Republic of Moldova.

And Russia will challenge American leadership not only in Ukraine, but please have in mind that now we have a gang of bad countries, with North Korea, with Russia, with Iran, supported by China, and if we lose this war in Ukraine, that means that first of all, the American leadership will get a huge question mark, because Russia will show to China, to Iran, and to North Korea, that a country with a GDP similar to Italy has the possibility to win a war against Ukraine, but a war against United States, against NATO, and EU.

Luke Coffey:

Great, George. George alluded to some of the possible scenarios, especially some of the more worst-case scenarios that could result in a Russian victory in Ukraine. But if you want a very sobering read, there’s a couple of chapters in the report that lays out these possible scenarios in alarming detail. And the scenarios you outline in this report are not inconceivable. They’re very real, and they should serve as a wake-up call for policymakers and lawmakers as they debate how we should assist Ukraine in this conflict. So I highly recommend you check out those sections in this report. Antonia?

Antonia Colibasanu:

I feel like I have to say a few words of why another report about the Black Sea. On my part, the why was related to my field of work. I’m a geopolitical analyst, and I’ve started working on the Black Sea, I will not say how many years ago, because that is not good, but basically, the borderlands have been my preoccupation since my years at Stratfor, and then as I evolved into a geoeconomic analyst, the Black Sea has also evolved into a very interesting place on Earth, and I will underline Earth. Speaking about the map’s look, I think that we should take into account that we are actually living on a globe, which is pretty exciting if you think about the location of the Black Sea on the globe. It is a connector when we are in peacetime, and it is a geopolitical node, which is not really nice when conflicts start.

So for the geoeconomic field, we actually have a two-purposes sea. One is that of coming together, corridors, trade routes, you name it. Cultures, civilizations, the Middle East meets Asia and Europe. But also, we have major powers that need to go south, that is Russia. We have connector powers like Turkey that need to balance off other major powers. And we also have the West, that has always played a role in shaping up the Black Sea, in shaping up the Eastern Mediterranean, in shaping up Eurasia.

And bottom line, the Black Sea is currently talking about challenges, and I have here two experts that are good at making lists of risks and challenges. And I am too, but I decided that for this report, I’m going to focus on opportunities. So bottom line, I am looking, and I was looking, and while doing the research for this one, first, why is it important for the US to look at the Black Sea, to consider the Black Sea on the globe beyond the risk of Russia. Second, what can we do to make it better for us all, and transform the risk into an opportunity as the business management calls for us to do?

So first, why should the US be interested beyond the fact that the US is interested in keeping Europe out of war? And currently we have a war at the very front line of Europe, with Romania being on the front of this war. And therefore, the risk of Europe entering the war is not something that we should neglect.

Second, why should the US be interested, considering the opportunities? Well, first of all, the northern corridor is less used, even if it is somewhat used. And we will likely have to go into peace-building actions after the kinetic war in Ukraine is over. Which means that that northern corridor, which transports Asian stuff into Europe and European stuff into Asia, is not going to serve very much. Therefore we have a Black Sea that supports the transfer of goods, and services, and influence, from Asia into Europe, from Asia into the Mediterranean, from Europe into the Mediterranean, and a connector to something called the Red Sea, a very interesting spot of today’s world, which is likely going to stay interesting because that’s its job. But beyond the interestingness of the Red Sea, we also have the corridors that are being shaped by Russia, north-south, and obviously, the South China Sea challenges that are affecting the freedom of navigation in the Mediterranean and in the Black Sea proper, with the Black Sea being that node that transfers the software that goes with every corridor that will be supported into being built up.

What do I mean by that? Well, with new corridors being built up, and shadow shipping being the norm for Russia and its allies, we also have a new software in insurance, in banking, in anything that might have to do with security of shipping, which is something that the US should not forget. Because the US is very much interested in the oceans. This country borders two oceans. And with the tendencies that we are seeing considering this new software, I think we should be very much aware and very much on to doing what the US and the West knows how to do best: transforming this new software into our software, making sure that it is us that keep the comparative advantage.

Finally, the big challenge that we have is also keeping that transatlantic link together. And this too is an opportunity. We are seeing countries that we have never thought, in Romania, I’m a Romanian, to look east and consider that the Black Sea and Ukraine are actually on that map, are actually on that globe, and we actually have challenges. Countries like Germany and France who thought that peace is a given, they have realized that peaceful life is not a given. Something that we, the US, the West, Romania, other countries, allied partners in the region, need to take as an opportunity to discuss with them, to make certain that we keep that alliance formed so that we transform all these challenges into opportunities, and keep the comparative advantage in anything and everything we do.

This was my goal, at least, to transfer. I do invite you to go over the report. I know there is a lot to read. It’s like putting together notes from conferences, and dinners, and stuff, which is interesting, right? Because you get to meet people and you get to meet ideas when you meet people, and those are interesting. Those are in there as well. There is a lot of research being done on key elements related to the military domain. And there is also a lot of thinking done on how challenges could transform themselves into opportunity, and a plan of action, which I think is the key part of this report. What should we do on the three main pillars of geopolitics? Now, I have to take pride in that. Politics, economics, and military, so all of that is in there, and I invite you to check the report online and read it.

Luke Coffey:

Great. One quick observation I would like to make, if I may, in addition to all these important geopolitical and geographical reasons why the Black Sea is important, one thing I notice in my research over the years on the Black Sea is that the countries of the Black Sea, obviously other than Russia, are dependable partners and allies for the United States, and in fact, during the last five or six years of NATO’s involvement in Afghanistan, the five friendly countries of the Black Sea for the United States contributed one-third of all forces in Afghanistan, just the five littoral countries around the Black Sea, one-third. So this, you put your money where your mouth is and you step up to the plate when needed, so that’s also important, in addition to the geographical and geopolitical reasons of the Black Sea.

Matt, a quick question to you. In the report, when it comes to the United States and the Black Sea strategy that was produced by the State Department last October, you write about this report, or someone wrote about this report, I’m going to guess it could’ve been you, “The strategy’s recommendations also rely too heavily on descriptions of well-known issues, came with few additional resources, and failed to provide a clear roadmap for implementation.” Which I agree-

Matthew Boyse:

Yes, that was me.

Luke Coffey:

Yeah, I thought so. I agree with all that. So what needs to be done to correct that?

Matthew Boyse:

Yeah, I hope that the impression has settled in about, this is not just an area of the world that is far away from everything, kind of peripheral, and clamoring for US attention when there are really priorities elsewhere. I mean, there are other priorities elsewhere, obviously, major priorities elsewhere, but this is not something that I think we can ignore, because of all of the way in which it fits into so many different sectors. The Caucasus, the near east, the Mediterranean, not to mention the Eurasian landmass, and of course our core commitment to NATO. We sort of, Black Sea strategy at the end of the previous administration, which my group did, and then of course the clock ran out, and so it takes a while sometimes for new administrations to figure out what they want to do.

So finally two and a half years later they came up with their strategy, which is kind of a strategy, but more of a description of well-known things. Which it’s always better to have a strategy, even if it doesn’t say a lot, than no strategy. So kudos in that respect, it was a bit late, rather modest, and very few resources of any kind. And so, I mean, one would have hoped for a bit more ambition, but the fact is that there is now one. And the fact that the secretary spoke at this conference in Sofia yesterday, I was flabbergasted. Because it hasn’t been really up on his list of priorities. And even though his comments were rather limited and not a lot, the fact that he actually spoke on it is a good thing.

And of course, we’re hoping that the department will read this and then incorporate some of our ideas into the whole of government approach, which is supposed to be drafted this year. Because the State Department strategy, however important it may be, doesn’t reflect the totality of the interests that weigh into the Black Sea region, because it really needs to be a whole of government approach rather than just one institution.

Now, the administration hasn’t, to my knowledge, at least, it hasn’t been very visible in how it’s implementing the strategy that it initiated back last October. Maybe there is stuff going on there that isn’t very visible. I think it’s very useful to have these to actually demonstrate to the people who are watching that, yes, this is actually a live thing. It’s not another strategy. And the fact that the secretary spoke on it yesterday is a very good thing, but it requires more than that. It requires the countries of the region to see that the United States is doing more than it did before. And of course, there are some good stories in the region. But the more visible this is, the better it is, because the sense of, “It’s off there, it’s not in Brussels or Berlin or in Paris, not in Western Europe, it’s somewhere else,” that message is something that is not a . . . It has to be NATO finally has made the eastern flank more coherent in terms . . . Because for such a long time it was focused more on the northeastern corridor, which of course is totally important. But it was sort of the disparity of resources between the northeastern sector and the southeastern sector was rather significant.

Now, that’s been corrected to a large extent, so we have one flank, one presence. So you have that kind of more coherent approach to the eastern flank, finally, which is good, but it needs more resources, it needs more visible attention, it needs more signs that this is actually not just a document, but actually it’s a living, breathing approach to a geopolitically incredibly important area. Because this area will remain contested as long as Russia is there. On Crimea, it will be unstable. The vast potential of the region will not be realized. It has enormous potential that it will not grow into what it could be, especially if developments in Ukraine go south, and it will just be sort of a . . . This will have reverberations far beyond the region. So maybe I’ll just stop there.

Luke Coffey:

Yeah. The fact that this push, this initiative to force the State Department to development a Black Sea strategy originated in the US Congress is a good observation for our European friends and partners to appreciate how influential the US legislative branch can be in making US foreign policy, which is a lot different from many parliamentary democracies in Europe. I do believe in the US presidential system of government, Congress has more influence on foreign policymaking, and this is a good example of that, perhaps. George, you lead the most influential, effective think tank in Romania, you are here as a Romanian. But there are other countries around the Black Sea as well that the US and Romania has to work with. Turkiye, Georgia, Bulgaria, obviously Ukraine, but their views have been represented in the report. Throughout the research and the writing of your report, how did you factor in and how do you see the role of these other countries around the Black Sea in bringing about a safe and stable region?

George Scutaru:

First of all, I think that it’s impossible to discuss about security in the Black Sea without Turkey. And it’s necessary to engage Turkey in all these projects related to the Black Sea. And Turkey is important not because of Montreaux Convention. Today, Black Sea’s closed, and we can’t receive other navy support from non-river countries, from US, UK, or other NATO countries because of these restrictions of Montreaux Convention. But in the same time, it’s necessary to have in mind that Black Sea has two entrances: Turkish Straits, in the east, and Danube. And it’s necessary to use more Danube potential.

And we proved last year, and started with 2022 when Russia broke Odessa ports, and entire export of Ukraine has moved to Danube ports. At the time, Romania ensure 70 percent of entire Ukrainian transit. We started in March 2022 with 300,000 tons of goods transit through Romania, and in October last year, we reached the level of three million tons. It was a huge effortment by Romania, we invest more than $150 million to improve logistic capacity. And we prove that how useful is Danube. And you can create together, in this area, with Romanian ports, Galați, and Brăila, and Moldovan ports, Giurgiulești and Reni and Izmail, Ukrainian ports, a huge hub. Very useful, including for the reconstruction process of Ukraine.

And also, it’s important because other challenge for us is representing by mines. And it’s a huge danger for freedom of navigation. And Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey established an initiative to work together against mine threats, which was an agreement signed by these three NATO countries, and we have to wait for the approval of Turkish Parliament, but this approval will come very soon. And in three months, this initiative will start, and it’s good. Because, as I mentioned, we can use this framework also to protect our energy-critical infrastructure. In Romanian EEZ, we’ll start to build up, next year, the most important projects. From Neptun Deep we’ll exploit more than 100 billion cubic meters of gas, to assure entire consumption of Romania, but also to help Bulgaria and Moldova to decrease the pressure from Russian side. And on the other hand, we expect a lot of Russian hybrid activities. And it’s necessary to work together with Turks and Bulgarians to protect better our critical infrastructure. And this initiative, focused now only on mines, I think you can extend the framework, and also to try to protect, first of all, with Turks, because they have also a very good and rich perimeter in their EEZ, Sakarya, with a lot of resources of gas, and you can protect together with Turks our Neptun Deep perimeter and their Sakarya perimeter.

And last but not the least, I think that all three countries play an important role to support Ukraine. Romania as a transit, first of all, because we assure, as I mentioned, 70 percent of Ukrainian export must transit these countries. Bulgaria has a very important role to support with ammunition Ukraine. And Turkey also has an important role to support Ukraine. For instance, they open a Baykar factory on Ukraine, and they will build more than 120 Baykar drones. And also what it’s important to understand, this asymmetry. One of the lesson learned of this war in Ukraine up to now, despite the huge consumption of ammunition, is the asymmetric approach against Russian fleet.

And why there? Because we discuss a lot about drones. I want to offer you a copy of Ukrainian MAGURA V5 drone. By the way, it’s made from same material like a real drone. And this drone, with this drone Ukrainians destroy more than one-quarter of entire Russian fleet in the Black Sea. It’s very incredible how country without fleet has capacity, using these asymmetric tools, like sea drones or aerial drones, and to hit and destroy one-quarter of Russia fleet. This is a gift coming from our Ukrainian friends to you, and to put on your desk, and remember how effective are Ukrainian drones, and how important is to support Ukraine to win the war.

Luke Coffey:

Well, thank you very much for that. My two young sons will love playing with this in the swimming pool this summer, I have to get a little fleet for them I think. No, thank you, George, sincerely. Antonia, I want to pose the same question to you that I posed to Matt, but switch it. Instead of what should the US be doing more of, what are some practical things Europe, however you want to define it, institutional Europe, geographical Europe, what can Europe be doing more of in the Black Sea? And then we have time for a couple of questions from the audience. We do have a microphone somewhere. If you’re interested, catch my eye, and then I’ll come to you after Antonia.

Antonia Colibasanu:

Sure. So first of all, there is a problem of definition there.

Luke Coffey:

That’s why I left it broad, for you to interpret.

Antonia Colibasanu:

Right. If we take Europe as European Union, I would say that the European Union is the most important donor on everything that was not military aid for Ukraine. Considering statistics at the end of 2023, that is. That being said, there is a lot and has been a lot of investment in infrastructure that the EU has helped with, together with the nation-states that were directly involved in building up that infrastructure. For instance, Romania, we have made a lot of effort to basically invest and rapidly allow the transit, as George pointed out, and that was not something that we have done without the EU support. It is actually through the EU funding that we have been able to do this rapidly.

Besides that, there is that Europe that is part of NATO. And that Europe that is part of NATO and the EU is now challenged by the hybrid warfare that Russia is conducting on it. Because if there is something that we need to remember about this conflict in Ukraine is that Russia is not at war with Ukraine proper, or not only with Ukraine proper. It is at war with the West, and it is primarily at war with Europe, with which it started the conflict years ago, after the Cold War ended, and after Russia started to implement its strategy with respect to energy in particular, and making Europe dependent on energy.

So what can Europe do? Well, making use of what it has. Energy resources and critical resources, rare minerals. There are discussions now in the European Union to modify part of the legislation that allows investment into rare minerals, some of them to be found also in the Black Sea area in Romania, for instance. And obviously, some of the energy resources also found in the area, the Black Sea.

However, Europe is weak on its military domain. So it can do a lot of things related to easing up the frameworks that allow for opportunities to be sought, because of this conflict, or due to this conflict, arising to that point of making the European countries more attractive for investment, and also getting back to that attractiveness that got us in the Eastern Bloc integrated into the European Union in the first place, the reason that the Cold War was won, if you like.

And besides that, the European Union, European states, European whatever, especially those that are members of NATO, need to build up their military. I think that they have realized that. There are some European states that are now drafting their own Black Sea strategy, France is one of them. At the same time, I believe that Germany is pretty much pushing forward with building up the military industry. I’m not very certain that I am feeling very confident with only Germany doing that in Europe, for reasons that have to do with my job. Geopolitics have a lot to do with history. But considering that we are allies, and that the containment line, the front line is now in between the Baltic and the Black Sea primarily, I think that the flank, the western flank needs to be really supported in terms of making sure that it is resilient, and that it stabilizes itself economically and socially with regards to Russian techniques and strategies. We are in an election year in Europe as well. And making sure that there is support for the long-time buildup of the military power there, for a good flank.

Luke Coffey:

So we have time for two. The gentleman there, and then, I’m sorry, the one in front. You know what? We’ll take all three together and then we’ll wrap up. So the gentleman here, the gentleman here in the blue, and then the gentleman in the back, if you could please state your name and any relevant affiliation, and keep it like a pithy question so we can be mindful of the time, thank you.

Greg Scarlatoiu:

Thank you. Greg Scarlatoiu, US Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, [foreign language]. Thank you for your presentations. You mentioned, President Scutaru and DR. Colibasanu, two very important areas, fossil energy and agriculture. What is the current state of Romania’s arms and ammunition industry, another great area of potential? It took a big hit after the Cold War, it has recovered to a certain point. It’s somehow lagging behind Bulgaria and Serbia. To what extent is the industry vertically integrated at home? Do Romanian producers have to depend on imports of propellant and everything else that’s needed? So is this regarded as a potential area of growth, and is there a national strategy, a national vision? The other area would be Romania as a hub of reconstruction and development in Ukraine, in addition to being a very important point of transit. Is there a coherent national strategy addressing that? Thank you.

Luke Coffey:

Great. And then we’ll take the . . .

Chris Orr:

Ah, good morning. [foreign language] Antonio, George, good to see you again. I’m Chris Orr, previously senior defense editor for 19FortyFive, now I’m dual-hatted as a military aviation writer for simpleflying.com, as well as publisher of the Patreon page D’Orr-senal of Democracy. As you may recall, a few weeks ago I published an article on the Romanian Air Force, talk about their transition from the hopelessly obsolescent 1950s-vintage MiG-21 Fishbed fighter jet to the fourth-generation F-16 and the fifth-generation F-35. So I was wondering if you have any insights on as to how that transition is coming along, how well the Romanian Air Force pilots are making the adjustment, and are they happy with the change? Thank you. [foreign language].

Luke Coffey:

And then the gentleman in the back.

Audience Member:

I work a lot on Moldova, and just today the Moldovan government announced they’re going to hold presidential elections on October 20th, and there’s also going to be a referendum about Moldova’s EU aspirations on the same day. Given Romania’s historical relationship with Moldova, including being the same country a couple of times, how can Romania and, by extension, the rest of the European Union help Moldova in the coming months leading up to the elections and beyond? Thank you.

Luke Coffey:

Great. So we’ll go in order, you can answer as you like, or don’t answer at all. We have ammunition manufacturing capability in Romania, reconstruction efforts that could be originated in Romania for Ukraine, future of the Romanian Air Force, and Moldova. I’ll just go, George, you want to go first, since a lot of the focus on your area?

George Scutaru:

Yeah. About reconstruction, Romania could represent an important half of the reconstruction [inaudible 00:49:43] as part of Ukraine. As I mentioned, it can create in the south and eastern parts of Romania, a huge hub, together, of logistic, first of all, together with Moldovans and Ukrainians. And I think that Romania also has proximity, as I mentioned, to southern part of Ukraine, one of the most affected regions part of Ukraine by the war. But in the same time, you have energy. And you want to produce cement for material constructions, it’s necessary to have access to a predictable and long-term energy sources. And Romania will have a lot of gas, as I mentioned, starting 2027, Romania will be the largest gas producer in EU, because we’ll start to exploit our gas reserves from economic exclusive zone of Romania.

Regarding ammunitions, in that, we have to enhance our capacity to produce ammunitions, and Rheinmetall, German company Rheinmetall, decide to invest in Romania, will be one of the biggest powder plants in Europe, in, I think, in one and a half, two years. But in my opinion, why it’s so important. Sir, if you have a ceasefire, it will be just a break. Putin will restart the war. And it’s necessary to be prepared for a longer war in Ukraine, and it’s necessary to support and to enhance our support to Ukraine. This is the reality. At the moment, Russia is producing more ammunition than US and EU together. And this is the reality. It’s necessary to enhance our production of ammunition, especially because we are very close to this war.

And regarding your questions, it was a huge transition and amazing transition for MiG-21 to F-16. Now we receive two new squadrons of F-16 from Norway, but the biggest step for Romanian Air Force is represented by F-35. The most important decision by Romanian parliament two, three months ago was the decision to approve the acquisition of 32 F-35 airplane. It’s an important contract for American industry. $6.5 billion. And I think that together with Poland, Romania and Czech Republic also, Romania, these three countries will have an important number of F-35, and represent the core of NATO deterrence on the eastern flank.

Indeed, we count a lot on F-16 and F-35 as a deterrence too against Russia. It takes time to build up all this infrastructure necessary to use F-35 airplanes, and for this reason we modernize our air bases. We invest, for instance, $300 million to modernize Campia Turzii Air Base, where we have deployed F-35. Also Romania has started an amazing project to modernize Mihail Kogălniceanu Air Base, where you have now 5500 American soldiers. When we’re finished this project, MK base will be the largest in Europe. Romania invest $3.5 billion. We invest a lot, and host nation support, to assure necessary conditions and to have an important number of American soldiers, first of all, but we have also more than 1000 French soldiers on our soil, to have an important deterrent and robust deterrent instrument. Because we failed to deter Russians in 2014, many countries in Europe preferred to feed the beast, with our goodwill and money for cheaper gas. And we know the result of this kind of policy. Now we have, again, a war in Ukraine. And it’s necessary to be prepared, and Romania is doing a lot to invest in defense capabilities.

Regarding Moldova, I think that, as I mentioned, you have a full-scale warfare, hybrid warfare against Republic of Moldova. In November, we’ll have presidential elections, and please, because many people watching to Transnistria, but please have in mind the Gagauzia. Recently, two weeks ago, the Gagauzian governator, is a lady, is visit Russia. She met President Putin, and Putin wants to provide a lot of help, not for Gagauzi people, but, frankly speaking, to undermine and to destabilize Republic of Moldova. We will support them, EU provide a lot of support money together with the US, EU has provide $300 million to balance Moldova’s budget, to help them to overlap the problem of prices for energy, and Romania provided oil, wood, gas, money to support them to hold the line against Russian pressure. The pressure is huge, but it’s important for all us to understand that we have to continue to support Moldova. So together, with [inaudible 00:56:02] and with Brussels, with Brussels, and really in Bucharest, we are doing a lot together to support them.

Luke Coffey:

Thanks, George. I think those were very comprehensive answers to all of those questions. Antonia and Matt, do you have anything you want to add, any final remarks before we wrap up today?

Antonia Colibasanu:

I think that if I start, we might not get to lunch. So probably I’ll sit here and just not say much more.

Matthew Boyse:

I don’t have much to add on the Moldova side, I defer to my Romanian colleague, which is always so great to have. When you’re talking about the Black Sea, you really need to work with Romanians, because they really know so much about this. But I would just add that the centrality of Crimea to all this. Because I mean, this real estate is profoundly important from a geopolitical standpoint. And it’s, I mean, if you look at, for example, all the . . . Because the narrative is that the Russian fleet is no longer there in quite the same way it was before, et cetera, but the study goes into an awful lot of detail about the Russian assets that are still there, and the extent to which that actually provides this kind of, it’s bit of a cliché, but this unsinkable aircraft carrier, and the extent to how important it is for Ukraine to, if it wishes to retain its sovereignty within its internationally-recognized borders, Crimea is a massive issue. And I mean, you have now, the Russians building grand lines of communication to connect mainland Russia to Ukraine in the event that something happens with the Kerch Bridge.

You have, I mean, the A2AD bubble that’s . . . It’s sometimes thought that, “Well, that’s being degraded by . . . The Ukrainians are degrading it.” Well, yes, they’ve had some successes there, but there’s an awful lot left. You have the whole EEZ, and that is now, Russia dominates that. It’s not as though many will contest that. You have the jamming activities that the Russians have been on with regard to Bulgarian assets. And then you have this whole, I mean, the Russians even downed an MQ-9 drone last March, a US drone, it wasn’t much there. So the point is that there’s an awful lot of military assets that are still left in Crimea, and while the maritime domain is going in the right direction, that area is of enormous military significance still. And so you have this ability to squeeze Ukraine, and the grain corridors might be open right now, but military people say that Russia can still take that stuff out if they wish to do so, they just haven’t chosen to do so.

So I mean, there’s a positive narrative on there, which is all very good. But then if you focus on what Russia still has there and what it could choose to do in the future, especially if the land domain starts going in the wrong direction, that’s when you start to worry about the long-term geopolitical direction of that whole region, because it’s all connected. It’s not just sea, it’s not just water, it’s also the whole area around it and the effect that that has.

So anyway, and of course you add the whole, the Russians are building a base in occupied Abkhazia, which of course is further away from Novorossiysk, so that Russian fleet that’s been moved to Novorossiysk is no longer quite as vulnerable, and that supports a longer-term project. But the fact is that’s out there, and so all these things together, I think they merit a bit more attention than people have been paying, and because of the implications of what happens if the land domain goes south. And that’s what people need to be thinking about, the plan of action that we have, there’s all sorts of ideas which I won’t go into here, you can look it up in gory detail in the study by downloading the QR code in the tab behind us. But it’s been a pleasure working with you, I think we sort of, the combination of Romania and Ukraine, now we just need to think about this more from a Bulgarian and from a Turkish standpoint, and of course the Georgian standpoint, and we’ll have it completely covered.

Luke Coffey:

Absolutely. Well, George and Antonia, thank you so much for flying over here to be part of this in person. I know we value the friendship that we have on a personal level, but also on an institutional level, between Hudson Institute and the New Strategy Center. We really value that engagement and relationship as well, so thank you so much. Thank you, again, to our viewers, both in-person and online. You can find this fantastic report by scanning this QR code, which is very technical for us here at the . . . for me personally, but if you know how to do that, go ahead. Or you can go to hudson.org and find this report and many other fantastic reports on the Black Sea or the greater Black Sea region, all at your disposal. So thank you so much, and until next time.

Antonia Colibasanu:

Thank you.

Join Hudson for a discussion on challenges and key areas for cooperation in the global AI development competition.

Hudson Institute’s Devlin Hartline will host copyright law experts Zvi Rosen, Ben Sheffner, and Jake Tracer for a discussion on what the Supreme Court may decide and why it matters for the creative industries.

Hudson’s Center for Peace and Security in the Middle East will convene policymakers, experts, and private sector leaders to examine how antisemitism, both foreign and domestic, threatens American security and Western civilization.

Join Hudson for a discussion with senior defense, industry, and policy leaders on how the US and Taiwan can advance collaborative models for codevelopment, coproduction, and supply chain integration.