Listen to Event Audio

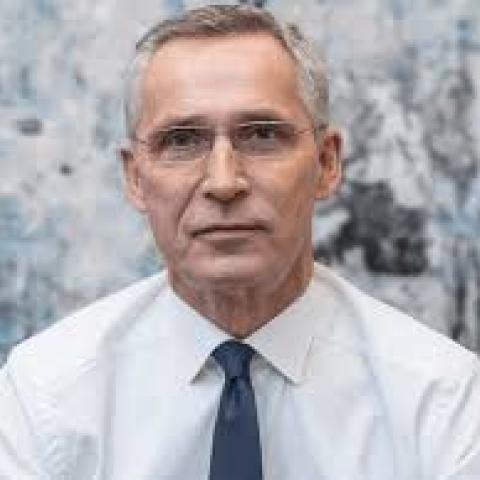

Join Norwegian Finance Minister Jens Stoltenberg for a conversation with Hudson Senior Fellow Rebeccah Heinrichs. Minister Stoltenberg will provide remarks about the nexus between security and economic strength from a Norwegian perspective. Then he and Dr. Heinrichs will discuss the security environment for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the importance of economic security and alliance cohesion.

Episode Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Peter Rough:

For 10 years as Secretary-General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization from October, 2014 until after the Washington Summit in October of 2024. For those full 10 years, then Secretary General Stoltenberg watched over the Alliance as Russia first made its move in Crimea and subsequently launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Secretary-General Stoltenberg, very close to my own heart, did us the honor when we launched the Center on Europe on December 1st, 2022 of transmitting a video message announcing the launch of the center. We then subsequently did an event on Capitol Hill, but today he’s joined by another one of my colleagues with her own initiative here at Hudson, the Keystone Defense Initiative, Rebeccah Heinrichs.

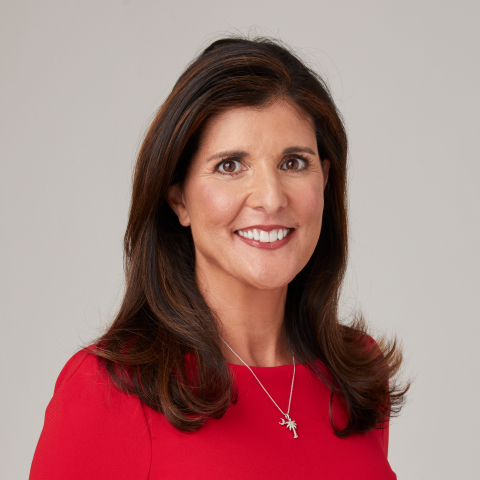

You will know Rebeccah if you follow national security at all. You’ve seen her on television, heard her on radio, read her in print. She works on strategic issues at the Keystone Defense Initiative, in particular our nuclear weapons posture, serving as a member of the Nuclear force planning Posture, a commission that Capitol Hill, that the Congress initiated a few years ago. There’s a great report which I would commend to you all that came out last year, and Rebeccah really is one of the leading voices for an America that’s engaged abroad, a conservative internationalism, if I could put it that way.

Secretary-General Stoltenberg, our guest of honor, really as I think about it, presided over a three-part play after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. First there was the Madrid Summit in which we adopted a new strategic concept that I think properly placed Russia at the heart of the problem facing the Western Alliance. Subsequently, in Vilnius, we ratified a new set of battle plans for the Alliance, and then finally at the Washington Summit, his farewell summit, the talk was about implementation, increasing defense spending and making sure that the Alliance is properly prepared to take on any challenge.

A European leader said to me in recent weeks, I don’t remember when exactly that was, that when it comes to Ukraine, the Northern Europeans do most if not all, the work in the Southern Europeans less so. Mr. Minister, you are now the minister of finance of Europe’s northernmost country, so the pressure is on and I look forward to hearing what you have to say about the war in Ukraine. Your current duties, a special meeting that I understand you have scheduled for this week here in Washington. And so I’d like to welcome you back to Hudson to the stage joined by Rebeccah Heinrichs. Please give them a well-deserved round of applause. Thank you very much.

Jens Stoltenberg:

Thank you so much, Peter. It’s great to be back at the Hudson Institute. Great to see you all and good morning. I will have a brief introduction and then I will sit down and take some questions. First of all, let me thank the Hudson Institute for what you’re doing because during my tenure as Second General of NATO, I really learned the importance of this institute, a well-respected institute that has deep knowledge of many issues, but for me in particular about security, defense and the transatlantic bond and that deep understanding is something that I really appreciated, not least because you demonstrated over all my years as Secretary General, your commitment to the transatlantic bond.

I’m here in Washington to attend the spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund, IMF, but also to meet with the advisor of the president, the economic advisor, Kevin Hassett. And tomorrow I’ll join the Norwegian Prime Minister in a meeting at the White House with President Trump to address a wide range of issues, security, trade, Ukraine, and other important issues which are on the agenda.

But now I will focus on some few remarks about economy security and the transatlantic bond. And I will start by saying that as a Norwegian, we have really learned to appreciate the transatlantic bond. I guess that most of you learned that the first European to discover North America or America was Christopher Columbus. In Norway, we don’t learn that. We learn that the first European to discover North America was a Norseman, Leif Erikson, and he came like 500 years before Christopher Columbus. The only problem was that he left after some years and forgot to tell anyone. But we have proof, there have been Norwegians, especially in Newfoundland and up north also 500 years before Columbus. And so that’s a part of the Norwegian heritage.

Another part was that next to Ireland, Norway is the European country where the largest part of the population immigrated to United States in the 19th and the 20th century. And my family was part of that. My grandparents moved to the United States in the 1920s. My mother is born in Patterson, New Jersey together with her four siblings, and then she actually married in North America, but then she met an Norwegian, divorced and came back to Norway. So then a lot of things happened. But so the transatlantic bond is also a part of my family history.

But then of course the Second World War and how the United States helped us to fight tyranny to defeat tyranny created a basis for the unique transatlantic relationship we’ve had since the second World War. And that relationship is built on two pillars, security and economy, security because of NATO and the United States, but also Norway were among the founding members back in 1949. Of course, United States brought a lot of military strength, but a country like Norway, a small country of, at that time, I think three million people or something, today we are five,. We brought proximity to the Soviet Union because in 1949, Norway was the only NATO ally bordering the Soviet Union. And we had the land border in the north with the Kola Peninsula and the sea border in the Barents Sea.

And as you may know, in the Kola Peninsula, we have the highest concentration of nuclear weapons in the world, missiles, strategic planes, aircraft and strategic submarines. And those nuclear weapons are not aimed at Norway. They’re aimed at the United States. So by having Norway as an ally so close to these weapons where Norwegian planes intercept the Russian strategic bombers, where we follow their missiles and track their submarines, we are making Norway safer, but also the United States safer. It’s a huge advantage for the United States to have a small country like Norway as an ally because we bring something that only Norway can bring, the presence in that part of the Arctic.

So my message is that yes, of course NATO, the transatlantic security bond is important for Europe, but it’s also important for the United States. And when I worked with President Trump in his first tenure when he was president, I was a Secretary General then, that was my main message that it is in the interest of the United States to keep the alliance strong, to have more than 30 friends and allies, that Russia, China doesn’t have anything like that.

And of course there are concerns in the United States about the strength and the growth of China, but the more concerned you are about China, the more you should be focused on keeping your friends and allies close. Because the United States represent 25% of the world GDP, the World’s global economy, together with NATO allies, we together represent 50%, half of the world’s military might and half of the world’s economic might. So it’s 50% of the world GDP and 50% of the world’s military spending together. So this makes again, the United States stronger.

Then it has been a fair complaint from the United States that European allies have not paid their fair share and therefore we made the decision back in 2014 that all allies should spend 2% of GDP on defense. At that time, only three allies spent 3% of GDP on defense. Last year it was 23 allies and more and more allies are actually exceeding the 2% and now at two and a half, three and some actually at four. The US is not now the biggest spender measured as percentage of GDP anymore. I think it’s Poland and maybe one of the Baltic countries. And this year I expect even more countries to exceed the 2% and even more countries to actually spend more than 3% of GDP on defense. So this is not the time to weaken that security pillar of the transatlantic bond when actually Europeans are stepping up in the more dangerous world. It’s even more important for Europe and for America keep together to stand together and to maintain this unique military alliance.

The other pillar is actually very linked to the security, and that’s also reflected in the founding treaty of NATO. Article two of the Washington Treaty is about the importance of economic interaction, trade economic cooperation between NATO allies to make us stronger. And the West, NATO didn’t win the Cold War because we fought a hot war with Russia or the Soviet Union. We won the Cold War because our economies were so much stronger, they were not able to keep up with our economies and our investments in defense, and therefore we need to understand why we became so strong economically and that was because he believed in open economies, trade competition between allies. And now we see some differences among allies on these issues.

But again, as a Norwegian, I know that we are exporting important products to the United States, some seafood, but also some critical minerals, metals, cobalt, nickel, which are key metals also for your defense industry. Norway has now made the biggest discovery of rare earth minerals in Europe, there’s a potential to do more and to be less dependent on China. And we also see that because of the need for scale, when we have Norwegian companies, we want to produce products for the American market, what they very quickly do is to actually establish production capacity in the United States. We have something called, a company called Norsk Hydro. They are now also producing aluminum in United States. We have a defense companies producing in the United States together with US companies. For instance, the NASAMs, the missile that are protecting the White House are Norwegian and American. It’s Kongsberg and Raytheon produce them together. And this is an example of how we trade and how we invest in each other’s economies.

So I believe, and of course we import things back from the United States, but it makes the Norwegian economy and the American economy stronger when we trade and invest in each other’s economy. The last example of our economic interaction makes us stronger is that the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund, which I had the honor of helping to establish in 1996 when I was finance minister the first time, some years ago, when we decided to then start to invest in equity, which was quite controversial at that time. The Sovereign Wealth Fund at the end of last year was 20,000 billion Norwegian kroner or close to two trillion US dollars. Half of that Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund is invested in the United States. It owns roughly 1% of all listed companies in the United States. It also buys fixed income assets like treasuries.

So 3% of Norway’s trade is with the United States, 3%, while 50% of our savings, 50% of the Sovereign Wealth Fund is invested in the United States. And that reflects a trust in the United States, and we have increased over the last year, we’ll continue to increase, and that reflects a trust in United States, which demonstrates how important the United States is for Norway, but also how important Norway is for the United States, that we are investing so heavily in this country. So we believe in the trust, we believe in the bond, we believe in the partnership between Europe and North America and between Norway and the United States. Thank you.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

Thank you so much for those great remarks. And thank you to my colleague Peter for that wonderful introduction. It’s a real privilege for Hudson to be able to host you here, and this is an incredible time. So I’m not going to bury the lead. You have an important meeting tomorrow. Peter had alluded to it, important meetings here in Washington. Can you tell us more about the plans for tomorrow and the message you intend to take into that meeting?

Jens Stoltenberg:

First of all, I look forward to meet with President Trump together with the Norwegian Prime Minister. I will also meet the Norwegian Prime Minister tonight, and tomorrow morning we will go through the details of the agenda. But when I spoke with the Prime Minister before I left Oslo, of course we expect to discuss at least four issues. One is security, including NATO. I will tell more or less the same story I told now about the mutual benefit of NATO for North America and for Europe, and that is in the US interest to have a strong NATO. This is something President Trump and I discussed extensively before. I guess we’ll address some of the same messages this time.

Then I actually forgot to do my introduction to also say that the other issue on security we’ll discuss is Ukraine. And my message is that we need to support Ukraine because it is in our security interest to support Ukraine. We are safer when Ukraine prevails, and therefore one of the first decisions I had the honor be part of as a new minister of finance in February, Norway was actually to triple the Norwegian military support to Ukraine. And we are now allocating close to eight billion US dollars for Ukraine, which is quite a substantial amount of money for a country of 5.5 million people. So security in NATO, Ukraine and the importance of supporting Ukraine are issues we will discuss with president. Then of course, trade and economy, and again, we believe in free trade, open trade, rules-based trade, and Norway having a small open economy, of course, we are dependent on trade.

And thirdly, I will expect us also to highlight some the areas where Norway is playing an important role in United States. Maybe I will mention NASAMs, I don’t know, but the NASAMs are really a product of US/Norwegian technology, two companies, Raytheon and Kongsberg developing a very advanced missile. We also now, Kongsberg is actually now investing in joint strike missiles and some other advanced missiles which they’re producing in the United States, so military cooperation.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

Wonderful. You had mentioned our cooperation militarily, specifically Norway and the United States. Just last month in March, they were Norwegian, F-35s escorted our bombers, and so thank you for the escort. And we are not just concerned obviously with Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine, but Russia continues to cause problems for the Alliance and for Norway and for the United States in the Arctic. And can you explain... And this is also I think a really concrete way in which economic security ties to military security is that we need to have free and open shipping lanes and Russia is heavily militarizing the Arctic and talk about that connection in Norway’s role there.

Jens Stoltenberg:

Yeah, I can talk about that in a moment, but let me first say that we not only escort US strategic planes, but perhaps more importantly we intercept Russian strategic planes. And we have a picture, it’s a beautiful picture, the ambassador has it, I think, it’s the first interception of a Russian strategic plane bomber up in the Arctic on the Barents Sea done by a F-35, a Norwegian F-35, which are excellent planes. And one of the things that make the F-35 so excellent is that they have technology and ability to share information in real time with. So this is actually, the unique thing with this one is that it’s a Norwegian F-35, the first time ever a F-35 intercepts a Russian bomber up there in the high up.

So we like to escort US planes, but even more important is to intercept the Russian planes. And we do this open in High North. And of course the High North is important, as you said, for strategic reasons. I had the privilege as NATO Secretary General to visit NORAD in the United States, but perhaps even more importantly in north of Canada. And we have the radars, we have, we have the sensors, we have all the systems to protect against Russian missiles because if you look at the globes not on the map, then you understand that the shortest way from Russia, route from Russia to the United States, not via Frankfurt airport or something, it’s over the North Pole.

So the High North, including the part of High North with Norway, it plays a key role, the Barents Sea, the Polar Sea, the Kola Peninsula up there, is essential for early warning protection of the North American continent. And therefore NATO and Norwegian presence is key again for all of us, so the security of all of us and we see China and Russia is increasing their presence and try also climate change, global warming, like it or dislike it, but the reality is that the ice is melting and it makes it easier to have different kinds of economic activity, but also major activity up at High North.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

And then you have articulated, I think quite well in the past that stopping... Part of the importance of enabling Ukraine to prevail and to end this conflict in a way that leaves Ukraine secure and sovereign and free is that it actually stops Russia there so that Russia does not continue its aggression elsewhere, including in the Arctic. They’re related.

Jens Stoltenberg:

Absolutely. I think that if Putin wins in Ukraine, he and also President Xi will learn a lesson that when they violate international law, when they invade another country, they get what they want. And that’s a very dangerous lesson to be learned by authoritarian leaders. And that’s also the reason why it is so obviously in our security interest to make sure that Ukraine prevails and that when we provide them with military support, it is in our interest. And if you’re concerned about Taiwan, South China Sea, the behavior of China, then you should be also concerned about what happens in Ukraine. And I think Ukraine is not only a kind of local regional conflict in Europe, you have to look at who are supporting Russia. It’s Iran with drones, it’s North Korea with enormous amounts of ammunition and soldiers. But then China is the main enabler of the Russian war economy, and they do that because they don’t want Ukraine to prevail, therefore this is much more than only a regional issue in Europe, it’s a global issue about whether democracy will prevail or autocracy.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

One of the comments that you made in your farewell address as Secretary General of NATO, one of the comments you said was, "That freedom is more important than free trade." But then you bookend that, "At the same time, this is important, security cannot be an excuse to introduce protectionist measures against friends and allies." So in the first warning, you’re specifically talking about European allies thinking that free trade meant that they could continue investments which resulted in dependency on our adversaries, Russians. Can you talk more about that and then also the warning then about China?

Jens Stoltenberg:

Yeah. No, I think we have to understand the difference between friends and enemies. And I also have to start by admitting that in the 1990s when I was minister for Industry and Energy in Norway and later Minister for Finance, I was part of a kind of global, I will say, surge in free trade all over the world. So we thought that including China in the global economy, trade more with Russia was good, partly because we thought it was good for commercial reasons, big markets and also commodities into the world market and not least by getting China into the world economy, but also because we believe that the more we trade with these countries, they would gradually become more democratic. We thought that free trade actually was a way to create freedom. We were wrong. And I cannot tell you exactly when I understood that, but sometime during the beginning of 2000s, we realized that for instance, being dependent on Russian gas, not Norway because we have our own gas, but for Europe, was dangerous.

But until the full-fledged invasion of Ukraine in 2022, most European leaders thought that buying gas from Russia was a commercial issue. It was an issue about free trade. It wasn’t a political issue. But then the United States, but also some other European allies, countries said that, "No, no, buying gas from Russia is a political issue. You cannot leave that to business. It’s about our security." And now we are in a... We should not repeat the same mistake with China to be vulnerable to depend on their rare earth minerals or specific commodities. And this is part about what we buy from China, we should not be vulnerable, expose ourselves for coercion from them. We should not sell key technology to them that they can use against us, and we should not allow them to control key infrastructure in our countries.

Back in 2019, during my tenure as Secretary General of NATO, there was a big discussion in Europe, whether we should allow Huawei to control the 5G network. And again, some said this is a commercial issue, leave it to the companies, we have to trust the market. Others said, "No, no, no, this is not a commercial issue, it’s a political issue."

But then I have to admit that there is a fine balance because we’re not isolating China, we’ll continue to trade with China. So there’s this balance between some trade but not too much trade, some investments, but not too many investments. And that’s a difficult balance to strike. But if you are not aware of that, how to find a balance, you’ll be off balance. You’ll be at the wrong place as many of us were at least some decades ago, where we thought that the more we trade with China and Russia, the better. That’s not the case.

So therefore, to try to answer your question, one thing is to restrict in different ways trade with authoritarian regimes that can use the trade to coerce us or to utilize technology against us or to control critical infrastructure, that’s dangerous. But the more we restrict trade with the authoritarian countries, the more we should be in favor of trade between democratic, open societies, friends and allies, and therefore we need to distinguish between friends and foes.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

And you’ve also been, I think you in your role at NATO and then President Trump really urging NATO allies to spend more on defense and security. But the other point you’ve made on the financial side though is that it’s going to require tradeoffs because as you increase defense spending, as Russia continues to be an acute and chronic threat to the alliance, even after we enable Ukraine to prevail in some sense of the end of this war, it’s going to continue to be a threat. Then the alliance has to do more, share more of the burden with the United States. There’s going to be tradeoffs. I mean now in your current role too, how difficult is that? Many of these countries have huge budgets for social spending and that’s going to have to cut into that as they increase defense spending.

Jens Stoltenberg:

No, it is extremely difficult. I think we just have to admit that. When I was Secretary General of NATO, to the East, I said, you have to spend more on defense. When I traveled around, that was my main task in a way since I became Secretary General in 2014, when we made the decision to increase defense spending, I think the single issue spent the most time on with allied leaders is to convince them to spend more. And they had a dilemma because when they land at the Zaventem Airport in Brussels, the first building they visit on the way into the center is NATO. And I told them to spend more and they said, "That’s very difficult." Then they came to EU and the EU told them, "You have to keep the deficit guidelines, to spend less." And then they went back and they were a bit confused because they were members of, most of these European country are members of two organizations, one says spend more, the other says spend less. And then they ended in different places.

But now they all understand that have to spend more. The problem is that if you have one billion extra for defense, you have one billion less for something else, health, education, whatever it is. And there are fundamentally ways of financing increased defense spending. One way is to reduce or cut spending on something else. It’s possible, but not easy, especially because what is often referred to as social spending or social expenditures, it’s pensions, mostly it’s pensions. And of course these are the rights that the population of these countries have based on their government funded pension systems. Some is also, a lot of is healthcare, but with more elderly people, you have to spend more on healthcare. So I’m not saying it’s impossible. I’ve been cutting public expenditure myself before and maybe I can do it in the future again, but it’s easy to say it’s hard to do, at least with significant amounts.

The other way of finance increased defense spending is to increase taxes. Yeah, I’ve done that too. It’s not easy that either. I lost some elections on that. So it’s not so easy that either.

And the third way is of course to borrow and borrow is always possible, but more and more countries now, NATO allies are now spending more money on interest rates than on defense because also borrowing comes with the cost, you pay interest. So this long intervention is about one thing, there’s no free lunch, there’s no free way of financing more defense spending. It’ll have a political and economic cost to spend 3, 4% of GDP on defense. So good luck to all those.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

I’m going to take some questions from the audience, and in the interest of time, I’m going to bundle them. So if you have a question for Mr. Stoltenberg, please raise your hand, say where you’re from, and then just a very brief question and then we’ll just bundle a couple of them and then turn it over to you. Okay.Wait, pardon me, the microphone right there.

Batu Kotelia:

Okay, thank you. My name is Batu Kotelia. I’m from Georgia, but now only here. I represent Foreign Policy Research Institute. So we mentioned Ukraine, and one of the ideas that is floating around now as a part of peace plan is Ukraine saying no to NATO. Do you think it’s a right one, morally or practically for future of the NATO? And what could be the other alternative for security guarantees better or equal to NATO?

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

We’ll do one more question back to back, and then we’ll let Mr. Stoltenberg answer them both, unless there isn’t one? One last one?

Dan Roper:

Hello, sir. Dan Roper with the Association of the United States Army, could you comment on the addition of Finland and Sweden to NATO and what Americans don’t understand about the cohesion of the Nordic countries and the security and economic lens like you talked to us about the US/Norway relationship? Thank you.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

Great. Okay, we’ll just take those two. So Ukraine and its future with the alliance and the importance of the cohesion of the Nordic countries.

Jens Stoltenberg:

Well, the best way to end this war, the war of aggression against Ukraine is for Russia to stop attacking a neighbor and to withdraw its forces and to respect the internationally recognized borders of Ukraine, borders, which actually Russia has recognized several times. The last time they signed the document, recognizing the international borders, including Crimea, was in 1994 when they signed the Budapest Memorandum where Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons in exchange of guarantees from the international community or the nuclear powers for the international borders. And then a few years later in 2014, those borders were violated by Russia. So this is the easiest, the only reasonable, or the only fair way of ending this war is for Russia to stop violating the sovereignty and the territorial integrity of Ukraine.

Then of course, the challenge is that the question is whether that it’s realistic, and then we all have to admit that maybe it’s sometimes you have to settle something which is second best and that’s what negotiations are about. But if I start in a way to say that the second-best solution is that Ukraine give us up A, B and C, including never to become a NATO ally or some territory, I don’t know, then I will undermine Ukraine and I will never do that. What I will say is that we need to make them as strong as possible on the battlefield because the stronger they are on the battlefield, the stronger they will be around the negotiating table. And of course, ideally they should give up nothing because they are attacked. If they have to give up something, it should be as little as possible, and it’s only Ukraine that can make those decisions.

So that’s my way of not answering your question, because if I... For instance, in membership of NATO, well membership of NATO is a right of every democratic European country to become a member if they so want and allies accept them as members, Russia should not decide whether countries can join or not join a military alliance. Some are saying that we have provoked Russia by admitting the Baltic countries, Poland, the former Warsaw Pact members into NATO. Well, it’s not an aggressive action by NATO. It was these countries that decided when they got their independence that they wanted to join NATO. It’s not NATO pushing them in. It is them asking to become members. And we allowed them in when they met the different criterias.

And this idea that if a small country Latvia or Lithuania joins NATO, it’s a threat against Russia so we should not allow them. It’s the same to say that we have re-instituted spheres of influence where big powers like Russia decide what smaller neighbors can do. And I’m coming from a small country, in Norway, bordering Russia. And I’m very happy that Washington and London and the big powers in NATO in 1949, didn’t say... And Joseph Stalin, he said there was a provocation against Russia that Norway joined NATO because we were so close to them. But I’m happy that Washington said, "No, no, it’s for Norway to decide." So if Norway had the year in the year in 1949, of course Latvia, Lithuania and at some stage Ukraine in the future should also have that right.

So I will never argue in favor of that right, but sometimes you end up in a situation, we have to settle for something which is second best because that’s what you can get, but the less they had to give the better. And the way to ensure that is to give military support to Ukraine.

Then that’s actually a way to move over to Finland and Sweden, because Finland, they fought bravely against the Red arm in 1939, in the Winter War, they had to settle for the second-best solution. They gave up 10% of their territory, they gave up the second-largest Finish city, Vyborg, and hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of Fins had to move, but they got the border.

And then, when was that? In 2023, they joined NATO. And then Sweden joined in ‘24. I’m correct now. Yeah, I should remember because I was part of it, but they are. And then Sweden joined and with Sweden and Finland in NATO, the Nordic region is part of the same security structures for the first time since the Kalmar Union, in the 15th Century. So the Nordics, we have been fighting each other for, the big Nordic war, the small Nordic war, the Napoleonic Wars we have... The last time Sweden was at war was against Norway and they occupied us and invaded us in 1814 and control us until 1905. So the Nordic country has been a quite violent region, but now we are the best friends, total peace. And the Nordic region demonstrates the way that countries that have been fighting each other for centuries can be friends. We have France, Germany in Europe, you have other examples. So it’s not given by nature that Russia has to be an enemy in the future. They can become a friend.

So I don’t know whether I answer your question, but I’m just trying to say that the Nordic countries are now more united, more together, and that actually also strengthens the security not only in the individual Nordic countries but also the whole alliance. Together, for instance, the Nordic countries have an air force of 250 fighter planes, it is a significant capacity. And most of them are F-35s, we have the Finnish armies, well-trained, well-equipped, we are training together, we are active together in southern NATO framework. So for me, it just yet another example of have a strong Nordic region in NATO, it’s good for... The Nordic region is good for Europe, but also good for United States.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

And I’ll just close that by saying thank you. Thank you for your leadership. The American people benefit so much from our alliance with Norway, from the alliance with NATO. Our security, freedom and prosperity is made stronger when our alliance is stronger. And so we’re thankful for that and we’re especially thankful for your leadership and we wish you all the best in your meetings tomorrow. So thank you for being here.

Jens Stoltenberg:

Thanks much, Rebeccah. Thank you.

Rebeccah Heinrichs:

Thank you. Thank you.

Jens Stoltenberg:

Thank you.