What China’s Middle East Policy Means for the US and Israel

Researcher, Diane and Guilford Glazer Foundation Israel-China Policy Center, Institute for National Security Studies and Nonresident Fellow, Atlantic Council

Research Fellow, Center for Peace and Security in the Middle East

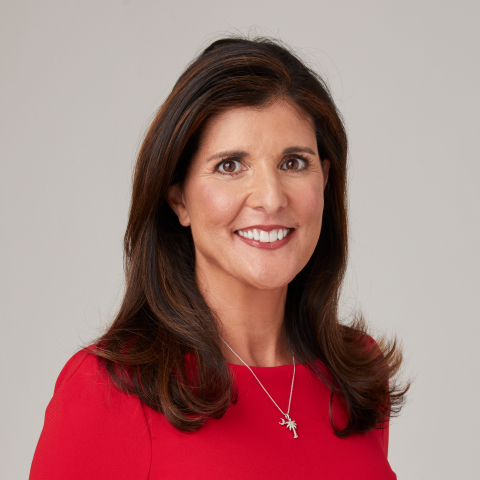

Zineb Riboua is a research fellow with Hudson Institute’s Center for Peace and Security in the Middle East.

Last year, Chinese diplomats brokered an Iran–Saudi Arabia deal that elevated Beijing’s status as a mediator in the Middle East. China hoped the deal would induce a greater “wave of reconciliation” in the region and strengthen its position. But Hamas’s October 7 attack on Israel changed Beijing’s calculations.

To discuss China’s ambitions in the Middle East, Beijing’s position in the Israel-Hamas conflict, and what this all means for American interests in the region, Hudson’s Zineb Riboua hosts a discussion with Senior Fellow John Lee and Atlantic Council Nonresident Fellow Tuvia Gering.

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Zineb Riboua:

Hello everyone. I'm Zineb Riboua, research fellow and program manager of the Center for Peace and Security in the Middle East at the Hudson Institute. Today I have with me two guests, and my colleague John Lee. John Lee is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute. He's also a senior fellow at the United States Studies Center, and an adjunct professor at the University of Sydney. From 2016 to 2018 he was a Senior National Security Advisor to Austrian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop. In this role, he served as the principal advisor in Asia and for economic, strategic and political affairs in the Indo-Pacific.

The second guest is Tuvia Gering. He's a researcher at the Diane and Guildford Glazer Foundation Israel-China Policy Center at the Institute for National Security Studies. He's also a non-resident fellow at in the Atlantic Council's Global China Hub. Previously, he was a research fellow at the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security, and the Israeli-Chinese Media Center. He's also the editor and author of Discourse Power on Substack. It's a newsletter covering leading Chinese perspectives on current affairs. So why don't we start with you, John. Can you just give us a greater vision of what perspective of what China is doing in the Middle East, and why is the Middle East important for China?

John Lee:

Sure. In the past, and I'm going back before Xi Jinping's time. China became a net oil importer I think in 1993. So, for around the 1990s and early 2000s, the Middle East was really more seen as a source of oil or source of energy imports. China put a very high emphasis on both security of supply, stability of supply and stable pricing. And it was always trying to come up with agreements and arrangements with Middle Eastern countries for that oil perspective. And just the reason why they were so worried about oil. The Chinese were always convinced that the United States would eventually lead efforts to constrain Chinese growth and development and not the blocking, but the limitation of oil or energy imports was always the paranoia that the Chinese had.

Now, Xi Jinping era since 2012, Xi Jinping is different in the sense that it's not just about energy security for him. Yes, it is about energy security, but more than this/ Xi Jinping, unlike its predecessors, sees China as a global leader. And being a global leader, you can't just call yourself a global leader. You need to be someone who is at least seen to be leading institutions, proposing solutions, and having relationships not just within the Asia Pacific, but beyond.

So the Middle East has become quite an interesting play for Xi Jinping. I would separate the two elements, there's the Iran element where China supports Iran to essentially mess up things for the United States and the West. China itself doesn't want to be seen as at the forefront of that, but it certainly supports the records in a system that is Iran, and Russia, and North Korea. But the more positive, or at least the more proactive version, if you like, or at least his ambitions in the Middle East, he wants to lead new institutions, new arrangements for commodity markets, financial markets. And the Middle East, from that point of view, is seen as a new avenue for Xi Jinping to start increase in Chinese power abroad.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah, and for you Tuvia, how do you see things playing out? Because I know that you wrote extensively about the Iran-Saudi Arabia broker deal in Beijing. Do you see that Xi Jinping has this vision of becoming a new hegemonic power, and needs the Middle East for that?

Tuvia Gering:

No, at least not yet. I don't think that China has any wish to become the new hegemony of the Middle East instead of the US. I think that in the current phase, it's trying to undermine US hegemony in the Middle East, and these are not the same things.

Looking at the talent that was brokered between Iran and Saudi Arabia in March of last year, '23, it surprised many people. Anyone who's been following China and its involvement in the region closely was also caught by surprise because it was unprecedented for China to be the leader in mediating this diplomatic coup, and the US wasn't even in the room. We know that the US took an important part in it with the Iraq and Oman, but still it was China that cut the ribbon. And all of a sudden you had this overflow of Chinese pundits and also other viewers from the rest of the world talking about the new Middle East, or a new phase of Chinese diplomacy where China is not only just an important actor in energy in the region, or in investment and trade, but also in diplomacy, and increasingly in security.

And around that time, just before China had unveiled its new security architecture for the Middle East and after that there was a global security initiative that was made by Xi Jinping after the war in Ukraine started. And that is part of two other global initiatives that are the Global Development Initiative and the Global Civilization Initiative, which were added to the Belt and Road Initiative, which marked the 10th anniversary in '23.

So these initiatives that are global in name are still need to remind us that hegemony is not necessarily what China needs at the moment or wants. I think the Chinese analysts believe that China does not have the ability to replace the US as a security guarantor, and does not want to be a security guarantor in the region, which is seen by them as a graveyard of empires. So the current phase, and this I think relates to what you said on Iran, is trying to undermine US hegemony, and this applies internationally. So the Middle East is just one piece of the puzzle. This is the same thing that happening now in Europe, the war in Ukraine, and the rest of the world, or the global south, as China sees it. And we can talk maybe about this mode later.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah, sure. This is a very important point on China's vulnerability, and how they actually cannot really totally replace the United States. But yet they are mobilizing, as you said John, Iran, and they are relying on it to put more pressure on US allies in the Middle East. And more importantly to give this idea of how the United States is in decline. And there's an article that John wrote in the Australian, Xi Jinping Conceals China's Vulnerability, Hoping We'll Fall for It. If you can expand on that and how do you see things?

John Lee:

Sure. Jinping, to his credit, and actually a lot of the Chinese leaders before him, they are very good students of American strategic history, particularly the last 70 years. So what they've done is they've looked at, how has United States preserved its preeminence? And they've realized, it's not just material power, it's not just military and economic. Obviously those two things are indispensable to preeminence, but it's non-material factors as well. It's institutional power. It's the power of legitimacy. And I think when you see China going around a world either in substance or at least in pretense, proposing solutions, negotiating peace, those sorts of things, China actually wants to be seen as a legitimate global power.

I agree, in the Middle East, it's not looking to supplant United States, it realized it can't do that. But in the Middle East it does think that in addition to the energy security aspects that I mentioned, it does think that it has nations there with Iran, but also with the Arab states where there are some natural complementarities.

For example, the Arab states don't have the same concerns as Asia Pacific states regarding China. They're not so concerned about Taiwan, they're not so concerned about South China Sea. They're not so concerned, necessarily, even if China achieves hegemony in its periphery in the Pacific. But the Middle East and Arab. . . All the countries as well, they're not really committed Democrats, if you'd like to put it that way. So yes, from a normative point of view, from institutional point of view, and material economic point of view, China thinks that Middle East is quite an attractive option around the world to extend its influence. But I agree, it's not looking to supplant United States as the primary security provider, but it does want more of an institutional economic, and a small. . . And somewhat of a military presence in Middle East.

Just on your question of Chinese vulnerabilities, China realizes that it doesn't have those ingredients that would allow it to sustain enduring preeminence that United States has. So for example, it's very paranoid about the way finance is organized in the world. The reliance on the American dollar, for example, which can be weaponized against China. It's very vulnerable about geography, in the sense that it still looks back to World War II and the Japanese experience of blockades against the Japanese, and those that could be used against it.

And finally, it does believe that it lacks normative and institutional power, because most of the institutions and norms that are still dominant were cobbled together after the Second World War, and were largely led by United States. China does say to itself very explicitly they lack institutional and normative power. And things like the global security initiative, that's what it's about. It's actually trying to elevate China's normative, or what they might call discourse and institutional power.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah. When it comes to actually for China to elevate its status in the world, and especially after the Iran-Saudi deal, there was this new marketing strategy that China is the peacemaker, the new peacemaker, the new UN. And especially it is using its power, or especially its influence, because there's a third world movement that developed in the 60s and 70s, and they have ties to Beijing in that way.

Now with the October 7th and the Israel-Hamas conflict, I think China is struggling here. They obviously have ties to the Palestinian question in a way that they convinced Hamas and Fatah to come to Beijing and to speak about it, and to have some sort of reconciliation. But they're still struggling because Israel is a very important US ally, and they need, actually, Israel to get access to more technologies, biotech, et cetera. I was interested in how you see this.

Tuvia Gering:

Yes. I think that after the pompous circumstance of March '23, with the detente that China brokered, October 7th, it betrayed the poverty of China's capabilities in their limits in the Middle East, and also how much it's willing to invest in security.

So after March '23, it talked about the wave of reconciliation, that it was China that led it. So it wasn't just between Iran-Saudi Arabia, but the whole region were talking to one another. It was Syria, a return to the Arab League, and Qatar started speaking with other gulfies, and so on. And this was China leading it. This is China is a new type of major power, showing that there are other ways to do things, other meaning other than what the US has been doing.

And here on October 7th, we've seen that China is not willing to invest quite a lot. It still says a lot, the rhetoric is very high, but the action is very little. A lot of symbolism, but on security, its response has been quite appalling from the Israeli perspective. Since October 7th until today, it refrains from criticizing Hamas in name, just talking generally about the need to stop violence against civilians, as if there's any moral equivalence between the two sides.

It still had no issue of criticizing and still criticizing Israel in every rising opportunity, and going above the fold beyond other countries, and making an example out of Israel, and reproaching it in order to curry favor with the Arab and Muslim world and the global south, and the rest of the world, in an attempt to undermine the US.

Because China is trying to frame the issue as such, that there's only one country that supports Israel, and that is the US, and it is the US that is single-handedly. . . And this is a quote by them, the Chinese foreign ministry. "That the US is single-handedly supporting Israel and vetoing it on its behalf on the Security council, while China represents the international consensus. It is China that speaks on the side of the Arab and Muslim world and all those that are oppressed, and on the side of the poor Palestinians."

And they see how the US is losing its image, its credibility in these regions all over the world. They see how it undermines the US from within. They look at the campus riots and they applaud it, and they look at the way that the US is also becoming more estranged from its partners on the other side of the Atlantic in Europe because of its support for Israel. And they just keep pushing all these buttons while fully supporting the Palestinians, also meaning supporting Hamas, and giving them legitimacy, and normalizing the terrorist organization without criticizing them, without talking about the hostages that are still being held in Gaza. Without talking about the Chinese that were murdered on October 7th, there was a handful of them, if you know or not. Because this serves this greater purpose, this greater strategy.

And most importantly, I came back from a visit to China with my colleagues three weeks ago, and one [Tsinghua 00:16:06] professor said. . . And it wasn't just him, there's a couple others. But they said that after two and a half years that the US has been using Ukraine to beat the Chinese for their support of Putin's aggression, so now China's using Israel as a stick to beat the American.

Zineb Riboua:

Oh, really?

Tuvia Gering:

And it's very easy to understand why they do it. It's all rational. I mean, from people-to-people ties and a humanistic perspective, it's inexplicable and it's beyond reproach. But from putting an analyst hat, it makes a lot of sense, because it's not just the war in Ukraine where the US, and its partners, and allies have been criticizing China for violating the rules-based international order. But it's also for seven years they've been claiming that China is doing a genocide and Xinjiang against its Muslim minority. And here you've got 2 million Muslims in an open-air prison that are committed against them the worst atrocities that are even worse than the Nazis, it's a genocide, it's crimes against humanity, as the Chinese are trying to amplify this message. And who's supporting them, who's giving their weapons? It's the Americans.

And this goes to show that the Americans are not really concerned about human rights or Muslim minorities, let alone the rules-based international order. They just want to contain China, they want to contain Russia, and I think that Israel and the war in Gaza is just a perfect opportunity.

And back to your question, I think this explains some of the lack of actions from China, because it doesn't have to do much for the US to tarnish its reputation and lose a lot of its resources. But also it also shows the limits of China before the war, that it won't even protect its own ships that are being attacked by Houthis, even though the Houthis say they would not attack Chinese and Russian ships, they still attack them. And China would not even go to help civilian ships sending stress signals, even though that trade from China and to China is affected by the attacks in the Red Sea. And that's also something we heard in China.

They told us we are the biggest victim of the Houthis attacks, believe it or not, and they still wouldn't do anything. Because you always have to keep in mind the big picture, the taju, and the taju is that the great changes unseen the century, the US hegemony is in decline, the east is rising, and here the Middle East is just one part of the puzzle, as I said. And you need to let this process of turbulence and war and crisis take its course. Hopefully the war ends with China reaping all of the benefits, and reputation, and the goodwill in the Arab Muslim world, the global south, and the US is tarnished, and it's just another blow to its hegemony in the region, and worldwide.

Zineb Riboua:

John, sorry, you wanted to.

John Lee:

Yeah, I just wanted to add just a little bit of further, I guess regional or Asian regional context to what was just said. The greatest arena of competition for China against the United States is of course it's periphery in East Asia.

And if you look at East Asia, many of the countries, particularly Southeast Asia, are not particularly close to Israel. In fact, I would say they're actually quite hostile to Israel and they're quite supportive of the Palestinian cause in whatever form that takes. So for China, it's a very easy way of undermining the standing of the United States on this Israel-Hamas issue.

Indonesia, Malaysia, even non-Muslim countries like Singapore tend to express a very strong support for the Palestinian cause, or at least believe that the American support for Israel is unfair and unbalanced. China playing up to that, and I know from my friends in these southeast Asian countries, that's what Chinese diplomats have been saying the last couple of months. And it's been a very concerted, focused message that China is the defender of Muslims, which is ironic given what's happening in Xinjiang, but the defender of the global south. So China has used this very cynically to beat the United States overhead. And its relationship with Israel I think is important, but it's not so important it would overtly side with Israel in any situation like this.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah, I can see that. I was in the Middle East recently, and I've met someone from Singapore, and I was basically asking him questions about Palestine and Israel, and he told me that initially, or usually people do not really, in Singapore, do not really have strong positions on that. And I told him, well, why now is it changed? What happened? And he told me that people now use a lot of TikTok. And it's true TikTok, that they get their idea about which position they should take, and how much Israel is such a horrible country despite. . . There's a lot of anti-Israel propaganda, a lot of anti-Zionist propaganda. And I found that interesting, that of all applications, he mentioned TikTok. And so it means how, and I want to get your insights on, do you see China mobilizing a type of information warfare capabilities against US allies, especially now Israel? Tuvia if you want to.

Tuvia Gering:

Yeah, so I've been looking a lot at this point, John mentioned of discourse power, which is high on the mind of Chinese thinkers and strategists. This is a buzzword. If you look at the Chinese IR literature, you see it mentioned often, and still is since Xi Jinping started mentioning it in 2013. And then later in 2014 in the first meeting on stand propaganda and foreign-related work, when he talk about the need to acquire discourse power.

And China has, as a communist party, a hundred years of origins of influence operations. And I think it'll be pretty unwise for the Chinese leadership not to exploit these kind of crises and wars to its narratives that it's trying to shape in a way to create this discourse power. Because they believe that the US, part of its hegemony is explained, as John said, by acquiring discourse power, by controlling the microphone, by being listened, by setting the narratives and standards, and then the rules of the international system.

So here in the war in Gaza, I think this point is vindicated by some of the surveys we've seen in the last few months. Also coming from Southeast Asia, you've seen from the Yusof Ishak Center, they do an Annual State of Southeast Asia survey. And there you see that for the first time that China became a bit more favorably viewed than the US, both at around 50 percent. And last week there's a huge article on foreign affairs from the people at Arab Barometer, and there they also showed similar trends in most of the Arab and Muslim world, and the Middle East and North Africa.

And now as talking about these platforms, I think TikTok is a special issue, and it merits a lot of attention, and it has for several reasons. As it relates to the war, I think it is more obvious that China is applying first its entire party state propaganda and foreign policy arms to make these messages that are anti-American, and anti-hegemonic, and anti-liberal. Before we even start talking about private companies that may or may not be under the influence of the Chinese Communist Party, I think just looking at the official discourse, you already see that China is trying to create for itself discourse power by exploiting the war, and the wars here in the Middle East.

And that aside, I think TikTok is a special case because it is a Chinese company, it's owned by ByteDance, and there's a lot of debate going on whether ByteDance needs to see to the different laws in China that force it to share information. And this is question of privacy and other things, but as forming opinions, I think there's no smoking gun yet showing that TikTok under the behalf of the Chinese Communist Party is trying to undermine the US. I think it'll be foolish for the Chinese not to use this kind of tool, I think it's very plausible, but I think the onus of trying to prove it is still not yet to be seen.

There are a lot of circumstantial evidence showing that after October 7th, there's a lot of bias against Israel and against Jews also in this app. And even when compared to other social media apps like the short videos on YouTube or on Instagram, you see that whenever there are Chinese talking points and narratives, then they get a greater emphasis on TikTok. And when it's something that is taboo, then it becomes a shadow band or gets less exposure than in these apps.

In Israel there's. . . One of the TikTok Israel hire employees who was responsible for government relation, his name is Barak Herscowitz. So he stepped down from Israel after October 7th, after he sent an international TikTok letter, or an article trying to prove the bias in the system of the app. But his calls were not heeded. He felt that there's a systemic antisemitism and anti-Israel bias in the system. When we met with him two weeks ago, still to him, there's no smoking gun showing that it is the intention of ByteDance through the Chinese Communist Party to make this kind of bias. However, he did point at the content moderators for TikTok that are sitting in the not most pro-Israel countries, for example, Ireland, or in the Gulf.

So having that in mind, I think TikTok merits a lot more attention in the future. I think that the way TikTok was able to send this popup message a few months ago, if you remember, to all of its users telling them to call their congressman, and because they know the location of all of their users, they send them their telephone number and then they overwhelm their offices. It just goes to show the potential of this app in shaping thoughts and moving the people into action. And imagine if something happens, God forbid, the Taiwan Strait or in the South China Sea where attentions are ramping up with the Philippines, and the app sends 150 million active users in the US a pop-up message telling them that this is justified, or trying to slant the content in China's favor to China's narratives. So yeah, I think it's just merits a lot of attention, to sum it up.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah, what do you think?

John Lee:

Well, I know in Asian Australia, TikTok does actively channel, censor, promote certain messages, and they all tend to favor China's interest. So we are not yet sure of the exact mechanism, the exact algorithm, how it's done, but there's a very clear correlation. I think what makes this issue, TikTok involved in this issue particularly ugly, is that in Australia, for example, if you look at TikTok in the past, there are lots of messages that seem very prominent that support China's stance in the South China Sea, for example.

But what makes this particularly ugly is a lot of the stance that people have in the current situation in Israel, Gaza, and I say this as a non-Jewish person, it is very plainly anti-Semitic. And so when China has weaponized this anti-Semitic sentiment, that adds an extra layer of ugliness and moral. . . It puts China in a far more morally compromised position than with these sorts of other issues. I don't think the Chinese would probably even think about it that way. They just see it as a way weaponizing issue for the interest against American interests. But that's the really ugly element to it, which I don't think the Chinese particularly care about.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah, especially with the student protest that you can see in New York and elsewhere. There is a rise of antisemitism that is, I would say, unprecedented. I lived in Morocco, the things I've heard here I've never heard before. And so there's definitely, of course, foreign actors putting themselves as the promoters of this.

But concerning also China, since we're talking about antisemitism, how do you see its relationship with Iran? Because since October 7th, Iran has also pushed a huge narrative, not only. . . Well, it pushed also its proxies more concretely, the Houthis, Hezbollah and others have joined Hamas in putting more pressure on Israel. The Houthis are still a problem in the Red Sea. I don't think that China is going to intervene because it's actually for them, such a delight to see the United States struggling. United States, especially the British too, struggling in that way.

It's true they're losing money, but I think that for Xi Jinping, I think it's more delightful them to see the United States with all of its capabilities struggling in that way. So they're aligned on putting pressure on US allies, aligned on several issues, but then how do you see it playing out? Do you think that their relationship is only going to grow? And what's the potential of its growth? Because obviously China needs Iran so that it can get closer to other Middle Easterners.

Tuvia Gering:

Yeah, so a lot to pick up there. The detente, I think in '23, it showed some of the ways in China increased its influence in the region, and especially with Iran. Today, China is the largest importer of Iranian oil, it's over 90 percent, according to media reports. And this is of course sanctioned oil that reaches China's shores through ghost flotillas, that they reach the eastern shores, and then through teapot refineries they are processed in China, and then this is the way of China providing an economic lifeline to the Iranians.

In recent years, except for this economic lifeline, China has provided the Iranians ways to limit their ostracism in the region and in the global stage. I think the most notable ones are through accepting it to the Shanghai Corporation organization, and then to the BRICS+, and institutionalizing relations with Iran for a 25-year deal as part of their comprehensive strategic partnership. And our caveat, remember that China has now.

Tuvia Gering:

. . . partnership. In our caveat, remember that China has now comprehensive strategic partnerships with five other countries. This last month they elevated ties with Bahrain to the same level. But before that China established comprehensive strategic partnership with Iran in 2016, in the same year it established with Saudi Arabia and with the UAE. No, sorry, the UAE was 2018, and Saudi Arabia and Egypt. And on that year you see that there's still a lot of investment that is going on to other partners, both the UAE and Saudi Arabia, and less to Iranians. And this has been a source of contention between China and the Iranians for many years, and still. Iranians still harbor a lot of ill will toward the Chinese because they feel like they've been betraying them or betrayed them at least three times by joining sanctions at their security council in the last decade or more. They believe that Chinese businesses are trying to undermine Iranian manufacturing.

So despite a lot of rhetoric, you see a lot of mistrust between these two countries, the same mistrust that is still held between Iran and Russia. There's a lot of historic grievances between all of these sides. Still because of the great power competition that is escalating over the years, and now with the war in Gaza and the greater Middle East and after this wave of reconciliation that China brokered, China is trying to keep the balance on the one hand in the Middle East, and it's a very precarious situation. And by balance, I mean not between the Palestinians or the Israelis, it's about the Gulf and Iran, which in their mind is the greatest source of instability. So if a couple of Jews and Palestinians die, that's something that they can contain. But if 90 million people of Iran riot and we get another version of the Arab Spring like we had over 10 years ago, then this could affect the whole region affect Central Asia and Europe and then China's core interest. And that's something that China's not willing to accept.

And for this reason, it's trying to maintain a balance by trying to normalize relations with Iran and the rest of the region, the rest of the Arab world. And that's what we see in all of these ties and 25 year deals and institutionalization of relations and the SEO and BRICS. And on the other hand, because of Iran's characteristics as an anti-hegemonic force in the region, I think to your point that Iran needs China much more than China needs Iran, that's certain, but still Iran does have value because it shares interest in undermining U.S. hegemony, the same reason that China and Russia share these interests. And again, there's not a lot of love between all these sides, but their shared hatred of liberalism, of interference of internal affairs and of U.S. hegemony in the world, I think put them in the same bed.

When we were in China, they told us we were forced to do the same bed. We have different dreams, but we were forced here because of the American and their pressure. And we are just trying to keep the balance. And whatever damage that the U.S. can accrue, then yes, I agree with you then it is China's delight. But I think China has greater interest in maintaining peace and stability. The only difference is there are many different ways to skin this cat. There are many different ways to reach peace and stability. And I don't think that a couple of dead Palestinians and Jews again are the top of Chinese considerations here, unlike the U.S. and its partners.

Zineb Riboua:

Do you have anything to add?

John Lee:

Yeah. Foreign affairs is only going to get harder for China because it's relatively easy to be a wrecker. It's relatively easy just to make life difficult for United States, which China has been doing. But when you start wanting to become a leader, not necessarily a hegemon, but a global leader, which means you take on responsibilities, you take on institutional responsibilities, you start taking on the responsibilities to preserve stability for example. And then by moving closer to one power, you often will move further away from another power. That's just reality of international politics, which United States always has to balance and will always struggle with.

Now China, if China wants to enter, for example, to Middle East, not as the primary player but as a major player, it has difficult decisions to make. If it moves closer to Iran, its relations with other countries will suffer and vice versa. So the point I'm making is that the more China gets involved in different parts of the world, the more it will become burdened with the squabbles and the complications of that part of the world. You can see that in the South Pacific, you're starting to see that in Southeast Asia and potentially in the Middle East. So all I would say is the Chinese should really be careful about what they wish for because it's not easy being that great global power that I think Xi Jinping eventually wants China to be.

Tuvia Gering:

Yes, I think I agree a lot with John. China right now is still trying to play this low risk, high reward game in the region and globally. And in some ways they think that they are winning if you look at these surveys. But then again, when you sift through the details and look at the small print, you find that it's not that China is succeeding much more when it's the U.S. that is failing, whether it's failing in its public diplomacy or just in its policies in the rest of the global south. So when you look at the Arab Barometer Service for example, it is not that these countries want to accept Chinese leadership now. They don't. They just are trying to air their opinions or disagreement with the U.S. that in their mind is undermining their interest or that of the Palestinians.

And I agree totally with John that China tries to reach the center of the global stage, Xi Jinping calls this mission, then you are under the limelight. You are not just the center of attention, you also see all the different failings of this Chinese leadership. And here I think in the Middle East, it's the best example, as we mentioned before. China perhaps thinks that it's on the side of fairness and justice standing with the Palestinians. But what they don't want to realize, because I think they do understand it, is that one of Hamas' greatest success on October 7th was the radicalization of an entire generation of Muslims all over the world and leftists all over the world.

And this has already reached Chinese borders and inside Northwestern China, the same reason that China is repressing its Muslim minorities, it's after terrorist attacks there since the nineties. And thinking that by normalizing this terrorist group that's supported by the Muslim Brotherhood, by normalizing Iran and by failing to criticize it while always criticizing the only Jewish state, and talking about the root causes, the only root cause is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but not looking at the other root cause, which is Iran is a revolutionary force for over 40 years that is spreading terrorism and undermining stability, not just in the Middle East, but also to Southeast Asia and to South America and to Africa.

And this will backfire. And Chinese analysts, at least the serious one, have been warning about it. Last week a professor Yin Gang from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences passed away. He was one of the loudest, clearest voices there on the Middle East. And that has been one of his biggest arguments that if China is not careful, as John said, not only will they get mired in the conflicts here, but also the leadership is shown in its poverty, which we do see it here. It also affects its ties with Israel of course, something we haven't mentioned. I think that the antisemitism that China is also using, I don't think consciously, I don't think Xi Jinping or Wang Yi are Antisemites, I don't think, they not at all, but I think that they are like the KGB at its time, are exploiting another point against the Americans, against the West, against the liberal world.

And all of this is not the community of shared future for mankind, this utopian vision that they're trying to have for the future of international relations. We're still going to deal with the Muslim Brotherhood and Iran subversive actions. And this will reach China. And I think we'll also see it in Central Asia with the Taliban. And this is something we should follow a lot closely. And for the Arab world, seeing Chinese actions or lack thereof in this war, it's also something that they pay close attention.

Because out there they'll say that they condemn Israel. But under the table and behind the scenes, Arab countries have also been dealing with the Muslim Brotherhood in Iran, despite the detent to Saudi Arabia. When we were in China, Turki Al-Faisal, who's a member of the royalty, he was speaking there at the conference of CCG, and he said that there's no trust with Iran, and as soon as they get a bomb, we're going to be next. So China's wave of reconciliation is a sham. Of course, still one of the greatest contradiction is between the Arab world and Iran and between the Arab moderates, which Israel belongs to this side and the terrorist and those who undermine peace and stability, that is China's interest after everything is said and done.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah. Well this is very interesting and very revealing of how much China is struggling. But then I can't but wonder what is the United States doing? There's obviously, I think the Biden administration also expressed how much they're paying close attention to China, that China's a challenger, that they're taking it very seriously. But then you both exposed China's vulnerabilities. That they do have weaknesses that there's possibility to capitalize on. But as soon as Beijing brokered the deal with Saudi Arabia and Iran, the first thing that the White House said was that, this is amazing. This is great. So obviously there is something missing in the U.S. Middle East foreign policy. Well first of all, it's really the Iran policy. They would like to accommodate Iran. And they came into office thinking they would revive the JCPOA. So there's this part that I was wondering, what do you think what the U.S. should do?

John Lee:

Look, I just think it's a function of the U.S. being, one, a global power, global responsibilities such that it's very hard for a power like that to keep its mind focused on some of its longer term challenges, namely China. And that's a function of the democratic process and the noise and contestation and chaos in messaging that happens in a democratic country. And I guess what I'm getting at is that the complaint about the U.S. is that unlike the Chinese, they don't do grand strategy, they just go from problem to problem. And look, that's largely true, although there are exceptions.

I suppose I don't really have an answer to it. I think it's just more a case that, going back to my previous point, if China's global influence continues to grow, it will start becoming like that as well. Because the world's not a simplistic place. Once you start having global influence, therefore global responsibilities, it's very, very hard to just pursue consistently a grand strategy, which is what China's trying to do. The U.S. doesn't do that particularly well, but that's just a function of I think their global responsibilities.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah. And for you, Tuvia?

Tuvia Gering:

I think that, and this is a problem I tell to my American friends and also to our Chinese friends when we met them in Shanghai and Beijing is it always feels like when we're speaking with them that there are only two countries on the map, it's the U.S. and China, and all the rest of the countries, they don't matter. It's just a great power competition. And unfortunately as the competition increases, intensifies, it seems that every aspect in international relations is seen through this prison. And this is unfortunate, especially for countries like us in the middle in Israel and the rest of the Middle East, where we would love nothing more for China and the U.S, the two largest economies to cooperate and fill the great infrastructure gaps, the development gaps that there are here, the security gaps and all these deficits, as Xi Jinping likes to call them, the four great deficits of trust, governance, peace, security and development.

But being realistic, we don't see this as the case. We understand that China and the U.S. increasingly viewing the region as another arena for great power competition. And for American policy makers listening to this, they need to understand the same for we told our Chinese partners, that they should try to cooperate if they can. And still it's not too late to try to cooperate on these issues of concern to international security like terrorism and Houthi attacks and Iran nuclear program. But I think that many would argue that it is too late. One argument we heard in China is you cannot expect us to change our policies now. It's been eight months and this is now a question of face. We have a country and a culture of face, and we're not just going to change course right now. And I hope that America does not share this same sentiment and it will continue to extend a hand when possible.

And it's not just only Iran that the U.S. and China cooperated in the past and the sanctions, but also in counter piracy. But now with the Houthi attacks, it seems that China is more intent on criticizing the U.S. violation of Yemen sovereignty, which is preposterous of course. And it doesn't seem like they're trying to change course on Iran. It's the opposite. I think that with Iran, they are providing this lifeline and they'll continue to do so and be extremely difficult to change course. And unless something terrible major happens, and we know as we speak right now, we might have a war at the north between Israel and Lebanon and Hezbollah, which is an Iran backed terrorist organization that attacked Israel since October 8th when we were down out of solidarity with the Palestinians. And a war is brewing and this war could affect the whole region and this will affect China's interest the same way that the Arab Spring affected China's interest.

And this could be a window of opportunity for both major powers to rise to the occasion and cooperate on something that is great effect to humanity. Because the ill wheel in cynicism is just too strong, I don't find this very plausible. I think that China will continue to exploit and undermine the sole security guarantor of this region. I think this is a strategic mistake on China's behalf, but this is the choice that China took under Xi Jinping and they're going to pursue this without being involved in military here. And if push comes to shove and the region goes into whole turmoil, then I really don't know what's going to happen. But I am sure that China will not become or not partake the responsible major power position that it self-ascribed.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah. So at the Center for peace and security in the Middle East, we really believe that Russia, China, Iran, are basically an access of convenience, but also of resistance to what they think is the great Saturn, which is the United States and its allies. And therefore they might disagree on so many things. They need to align on putting as much pressure as possible on the United States and making sure they are precipitating the erosion of its military diplomatic, soft power, et cetera.

But more importantly that because for example, for China, the pressing issue is really Taiwan, they think for Beijing not cooperating with the United States means that they are going to insert themselves in areas where they can grab a U.S. ally such as Saudi Arabia, which for the United States would be important because think of when China will invade Taiwan, one of the first things United States will do is implement sanctions. And then therefore they'll have to call Saudi Arabia, can you please help us? Especially on, as you mentioned earlier, John, on oil et cetera, can you help us with China and sanctions? And Saudi Arabia may simply say no. Why? Because of Iran and the Houthis, et cetera. But I'm interested in having your perspective on this. And do you also think that there is this calculus for Xi on the Taiwan question that makes him also more aggressive when it comes to his foreign policy in the Middle East?

John Lee:

China would certainly like the United States to be militarily and strategically distracted in elsewhere outside Taiwan straits and outside Asia. That's without a doubt, and that's very clear in its policies. But I think the Chinese are playing for danger here because you mentioned the Axis, China, Iran, Russia. But it is an Axis of convenience. But the difference for China, China's a far more globalized economy. China can't afford incivility, unlike Iran and Russia.

And the other thing when it comes to domestic priorities, the Chinese Communist Party cannot survive an economic disaster in my mind, and certainly in their own minds, they cannot survive an economic disaster. So it's all very well to create all these problems and global distractions for United States, but as mentioned or as it has been discussed, for example, if a region wide war erupts in the Middle East, China suffers a lot more domestically and internationally than the United States, in my view. So I think China's playing with danger. In many respects, my view is that Xi Jinping's ambition exceeds his state graph and his wisdom and things will get very awkward and difficult for the Chinese.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah. So to me I'm interested in your insights on what John just said, but also since you're in Israel, what can you tell us about Israel China relationship? Do you see a huge shift after October 7th?

Tuvia Gering:

Yes. So first about John's remarks. I think that the nature of Chinese relations with the Middle East and with the rest of the global south, especially after the Belt and Road Initiative, I think the whole purpose of connectivity of the Belt and Road Initiative through trade and finance and infrastructure and then in technologies and green technologies and transition and space, it's all to insulate China from these shocks that mentioned before in case China invades Taiwan or moves in the South China Sea against the Philippines and a war is erupting. It tries to insulate itself from the dollarized economic system to sanctions the same way that Russia has been trying to do so since 2014. It's trying to insulate itself in supply chain terms that it would not be so affected in its oil and trade and investment and everything, that the rest of the world would still want despite the Chinese invasion or a war, they would still want to continue these supply chains and maintain them and they are resilient.

And I think that it's not that China is creating havoc, but it is exploiting it for these purposes, including in the Middle East. And that's to the one point. The second point on Israel China relations. I think it's understood that our ties would not be the same after October 7th. I think that the mask has slipped off China after talking about this thousand years of friendship between the Chinese and Jews and 30 years of diplomatic relations, now entering this 32nd year. A friendship, there is no friendship, there was never friendship. This is about China's interest. And China, as you said, it still needs stuff from Israel, mainly innovation and technologies. And so long it needs this, and also they still hold a belief that Israel has some influence on the U.S, maybe a lot less after October 7th.

It's the opposite way. Now Israel is indebted to the U.S. because of its support. But still, as long as China believes that Israel has something to offer, whether on technology or in the region or more importantly providing China the image of this responsible major power that is mediating between Israel and the Palestinians, because if you want to be someone in the Middle East, you need to mediate between these two parties, right? So China would still want to maintain relations with Israel. And this, I think why they are hoping that after the war ends, will return to business as usual. And I think from the Israeli policy makers, you don't hear Netanyahu or foreign minister Israel cuts mentioning China at all despite its extremely hostile position since October 7th, because they're also trying to limit the damage to our relationship that China is doing by exploiting our suffering for all of its greater calculations.

This is a real politic consideration. And I think it's not just terrible, I think it also has some benefits to it because we understand this is also marriage of convenience to both of us. There's no partnership in values or systems. We are completely with the West and they understand it, we understand it, but we are sharing some interests with the Chinese and we'll continue to do so. And I think that's the future, but it really depends on the day after and what else is China going to do to harm Israel or exploit it for its great power competition.

Zineb Riboua:

And for you, John, how easy do you think is it going to be for China to go back to business as usual after the war ends? Especially since you mentioned how for China, it's really the is the peripherian matters, and so it might affect their image.

John Lee:

I don't think China can go back to business as usual. I'm not saying relationships end, but it won't be the same. As has been mentioned, the Israelis now it seems to me, has a fundamentally different view of the Chinese. Given China's support for Hamas, effectively, a lot of the Arab states will now be considering how much further they want to go with the Chinese, whilst the Chinese are effectively enabling the Iranians to do what they're doing. So it goes back to my early point that for the Chinese, I don't say this facetiously, welcome to great power politics, this is now a burden that they will increasingly have to manage.

Zineb Riboua:

Yeah. Thank you. Well, on this note, Tuvia and John, thank you for joining us and I'm sure the audience will find it very interesting and to hear from your insights.

Join Hudson for a discussion on challenges and key areas for cooperation in the global AI development competition.

Hudson Institute’s Devlin Hartline will host copyright law experts Zvi Rosen, Ben Sheffner, and Jake Tracer for a discussion on what the Supreme Court may decide and why it matters for the creative industries.

Hudson’s Center for Peace and Security in the Middle East will convene policymakers, experts, and private sector leaders to examine how antisemitism, both foreign and domestic, threatens American security and Western civilization.

Join Hudson for a discussion with senior defense, industry, and policy leaders on how the US and Taiwan can advance collaborative models for codevelopment, coproduction, and supply chain integration.