Anthony Albanese didn’t have much to report back after last week’s APEC summit in San Francisco. That could’ve been because the main event was really the sideline meeting between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping. Or maybe Albanese didn’t attend with a readied agenda as some have argued in these pages. It’s probably a bit of both.

As we digest the revelations that Australian naval divers were harmed by sonar pulses activated by a Chinese ship in waters near Japan, an important question is what a realistic and proactive economic agenda looks like vis-a-vis China.

Putting forward ambiguous approaches like stabilisation doesn’t help us very much, not least because we will enjoy neither stability nor predictability in relations with China. After all, putting our military personnel in harm’s way following a leaders’ summit to “reset” Sino-Australia relations is hardly evidence of China’s faith and good will.

But a good way to begin is to acknowledge that the world that gave rise to APEC is fading away, never to return. Even as recently as 2015, when Australia’s Free Trade Agreement with China came into force, economic interactions between countries were assumed to be immune to geopolitical tensions. This was at a time when there was a race to propose and join open and inclusive multilateral trade agreements under the World Trade Organisation framework. It is no coincidence that “inclusivity” is one of the key concepts currently being promoted by the APEC secretariat.

It is also significant that another concept being pushed by the APEC secretariat is “resilience”. Resilience from whom or what? It is not just a pandemic that has given popularity to that word. Open economies now nominate “resilience” as a key objective because of economic coercion and politically motivated trade punishments directed towards others – most damagingly and menacingly by China.

As the leader of the country most severely targeted by Beijing in recent times, Albanese should understand this better than others. Hence the contradiction between the APEC twin objectives of “inclusivity” and “resilience”, and the fading of a free and open trade world. Such an inclusive system cannot also provide resilience to most participants when the world’s largest trading nation relies so heavily on concealed subsidies, cheap finance and regulatory measures to entrench unfair advantages for its own firms in domestic and global markets.

Resilience in a blindly inclusive system is not achievable when Beijing routinely uses economic coercion against other countries. Instead, resilience is only possible at the expense of inclusivity.

Australia’s major strategic allies and partners, such as the US, Japan, South Korea, India and even the European Union, now accept separating economic co-operation, trade agreements and offering privileged market access from broader geopolitical objectives is untenable. Encouraged by their governments, firms in key sectors of those countries are diversifying away from China where possible.

Foreign direct investment into China has been declining every month in percentage terms by double-digits, with the pull-out led by advanced economies (mainly liberal democracies).

The US is pursuing bilateral and small-grouping economic agreements with its strategic partners rather than inclusive multilateral trade agreements. Geopolitically aligned economic groups will grow in number and relevance. This is not the world of APEC and it shows why so little of relevance happened in San Francisco.

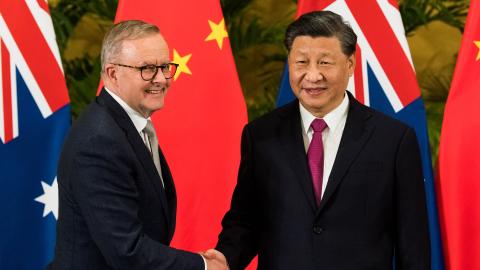

Having stumbled upon these realities in winning government, how much does Albanese care about strengthening national resilience? Let’s put his recent visit to China in context. Flying to China to re-establish top-level engagement is one thing, but travelling with a large business delegation in tow – following the torrid economic coercion perpetrated against Australia – sends confusing messages to a domestic audience, which is constantly reminded about the importance of diversification. It was as if the Chinese indiscretions from 2017 until now remain aberrations, with Canberra seeking a return to a pre-2016 era.

Of course, Albanese is not that naive and maybe it’s more a matter of poor optics rather than substance.

He does frequently acknowledge that China’s political system is quite distinct. But what about Beijing’s values? There was further indecision regarding the CPTPP economic pact which China wants to join. It is impossible for China’s political economy to meet the high standards of the CPTPP, but Beijing’s assurances that it will change its policies and behaviours cannot be trusted.

So why do we leave open the door in saying that Australia will still consider China’s application and, in doing so, isolate a Japan that is taking a more resolute stand on the issue?

This is what it is to seek stability with China. It is based on deliberate ambiguity, avoiding difficult issues and passively leaving differences between the two countries to play out in a manner of Beijing’s own choosing. It would be better for Albanese to lead and shape what the CPTPP stands for and put his energies into deepening relationships with economies that also seek to increase their resilience against Chinese economic coercion. There are plenty of victims to choose from.

This approach doesn’t mean endangering our essential trading relationship with China. The lesson of the last few years is that China needs trade with its advanced economy partners as much as they do with China. But Albanese should be clearer that this is not where the future alignment of geopolitics and economics lies.