rime Minister Justin Trudeau announced on February 28 that Canada would join the United States in its Lunar Gateway project, becoming the first international partner to officially sign on. The announcement came with a financial commitment of $2 billion over 24 years.

Then, on March 6, Minister for Innovation, Science and Economic Development Navdeep Bains launched a comprehensive new Canadian space policy Titled Exploration, Imagination, Innovation: A New Space Policy for Canada, the strategy sets federal research funding priorities for space science in four areas: lunar science, artificial intelligence, robotics and health. The goal is to highlight areas in which Canada has already developed deep expertise while accelerating cutting-edge research to ensure that Canada can continue to contribute as a partner of choice for the US and other countries engaged in space exploration.

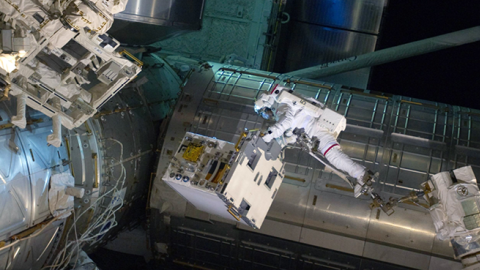

Additionally, the Canadian government will be developing the Canadarm3 — an upgraded version of the Canadarm used on the International Space Station — as well as investing $150 million in the Lunar Exploration Accelerator Program, a new initiative to stimulate space business in Canada.

The Lunar Gateway is a first-stage goal in the Trump administration’s ambitious space program plans. The station will operate in orbit around the moon and act as a platform for conducting research and development for deep space exploration. But it is an expensive undertaking, and the cost is driving the US to seek partners for the project. The Japanese and European space agencies are showing interest.

NASA has already issued a call for bids on the first component of the Lunar Gateway, the Power and Propulsion Element. NASA is also cooperating with the private sector to develop next-generation lunar landers through its Commercial Lunar Payload Services program. It plans to encourage commercial use of the platform to offset costs.

Trump reignited the US space program — and created new opportunities for Canada to contribute to new projects — with advice from the National Space Council, which has issued four Space Policy Directives so far. The first of these, signed by the President in December 2017, directed the federal government to “lead an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners to enable human expansion across the solar system and to bring back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities.” A key goal of this reinvigoration is to return humans to the moon, with the idea that this will eventually help with future manned missions to Mars.

Canada has an impressive space sector that is already well integrated in US space sector supply chains. The Canadian industry generated $5.5 billion in revenue, adding $2.3 billion to the domestic economy, in 2016. Canada’s space-related exports grew by 24 percent that year, with the largest portion of exports traveling to the US.

Economically and scientifically, Canada will benefit from contracts as well as the chance to participate in the global renaissance of space science that the revitalized US space program will induce. Canada’s extensive space robotics expertise will give it a comparative advantage over other international participants. These capabilities will be in demand for operations aboard the Lunar Gateway but also for eventual lunar-surface activities, such as landers and rovers exploring the moon’s abundant resources for space mining. Canada’s participation is more than just a maple syrup financial sweetener for US space projects.

Politically, Trudeau’s commitment to the Lunar Gateway was uncertain until now, following a year of tensions over trade that strained the US-Canada relationship and did little to endear the Trump administration’s priorities to Ottawa. The Canadian public investment will open up new opportunities for Canadian firms and universities and represents a win for the coalition behind the Don’t Let Go Canada campaign, which involved more than 70 Canadian firms and organizations. MDA, Honeywell and Canadensys and advocacy groups like the Planetary Society and the Aerospace Industries Association of Canada were in the lead.

The US might need Canada as a spacefaring partner more now than in the recent past. Russia’s space program has been in serious decline, made worse by international sanctions. Concerns about technology theft have led the US to ban cooperation with China in its space program or its commercial space sector. That leaves Europe and Japan, both of which have their own major projects under way, and India, which is focused on a nascent space program of its own.

The ambitious new Canadian space strategy is an important step toward defining Canada’s niche areas of expertise while maintaining Canada’s relevance to its partners. In weighing the political, economic and scientific arguments, Prime Minister Trudeau has taken the long view of space cooperation with the US. The two countries can achieve more together in space, and the potential benefits for humanity tomorrow are more important than misgivings about US leadership today. Ad astra per aspera!