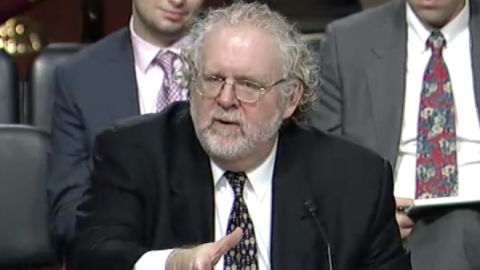

Walter Russell Mead's testimony begins at 54:00.

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member Reed, and members of the committee:

It’s a great honor to be invited to testify again before this august committee and its distinguished members. It is also encouraging to know that in a time of decreasing attention spans and in a political climate increasingly focused on “winning the news cycle”, members of both parties are taking seriously the long-term strategic planning needs of the Republic. My aim today will be to clarify the geopolitical situation we face in the early 21st century, the challenges and opportunities that are likely to arise going forward, and the grand strategy concerns of the United States that derive from these.

Background

After the Second World War, the United States replaced Great Britain as, in Col. House’s phrase, the “gyroscope of world order.” The U.S. assumed the burdens of global leadership not because we desired power—in fact, we had spent twenty years before the war, and two after it, trying to avoid global responsibilities—but because Americans needed the benefits of a stable world order to be safe and prosperous at home. Maintaining an open global economic system is vital to continued American prosperity. Maintaining a stable geopolitical order is vital to continued American security. And promoting values of freedom and self-determination worldwide is a critical element of these two missions.

These realities are still the basis of American foreign policy and national strategy today. While there are many disagreements about how these principles should be translated into policy, and while some Americans seek to turn their backs on the difficult tasks of global engagement, on the whole, the commitment to the principles of liberal world order building that have framed American foreign policy since the Truman administration continues to shape our thinking today. As the world becomes more integrated economically, and as new threats like cyberwar and jihadi terrorism combine with old fashioned geopolitical challenges to create a more dangerous environment, this postwar American foreign policy tradition is more important than ever, but we must think long and hard about how we address our vital interests in an increasingly turbulent and dynamic world.

The question before us today is whether we can continue to afford and manage the global commitments this policy requires. If, as I believe, the answer is that we can, we must then address questions of strategy. How do we harness the means we possess to secure the ends we seek, what priorities do we need to establish, what capabilities do we need to cultivate, and to what allies can we look for help as we seek to promote a peaceful and prosperous world amid the challenges of the 21st century?

We can begin by examining some of the advantages and disadvantages that the United States and its allies have as we consider how to adapt a 20th century strategy to the needs of the contemporary world.

Disadvantages & Advantages

Surveying the global landscape, we can see several disadvantages that make it difficult to maintain the global system we’ve built into the 21st century. At the most basic level, one of the chief disadvantages facing the U.S. is the never-ending nature of our task. America’s work is never done. Militarily, whenever the United States innovates to gain an advantage, others quickly mimic our developments. It is not enough for us to be ahead today; we have to continue to innovate so we are ready for tomorrow and the day after.

The U.S. is challenged by the products of its own successes in ways that extend far beyond weapons systems. The liberal capitalist order that the United States supports and promotes is an engine of revolutionary change in world affairs. The economic and technological progress that has so greatly benefitted America also introduces new and complicating factors into world politics. The rise of China was driven by the American-led information technology revolution that made global supply chains possible and by the Anglo-American development of an open international economic system that enabled China to participate on equal terms. The threat of cyberwar exists because of the extraordinary development of the “Born in the U.S.A.” internet, and the revolutionary advances that it represents.

In this way, American foreign policy is like a video game in which the player keeps advancing to new and more challenging levels. “Winning” doesn’t mean the end of the game; it means the game is becoming more complex and demanding. This means that simply in order to perform at the same level, the United States needs to keep upping its game, reforming its institutions, improving its strategies, and otherwise preparing itself to address more complex and challenging issues—often at a faster pace than before, and with higher penalties for getting things wrong.

America’s competitors are becoming more capable and dynamic as they master technology and refine their own strategies in response to global change. The world of Islamic jihad, for instance, has been transformed by both the adaptation of information technology and adaptation to previous American victories. In both these regards, Al-Qaeda represented a great advance over earlier movements, Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia yet another advance, and ISIS a further step forward.

In the world of international geopolitics, Russia has also made much of information control and its current leadership possesses a keen eye for the weaknesses of American-fostered successes such as the European Union. And China is also emerging as new kind of challenge, one that on the one hand plays “within” the rules much more than Russia or ISIS, but on the other, is still willing to break the rules—viz. the OPM hack or industrial espionage—when Beijing feels it is necessary. Far more than America’s other competitors, China has used this combination to develop its own economy and to lay the foundations for long-term power.

Meanwhile, many of America’s traditional allies in Europe are losing ground in the global economic race, and NATO, the most successful military alliance in world history and the keystone of the worldwide American alliance network, is in trouble. Many of Europe’s leading economies—which is to say, many of the top-ten economies of the world by GDP—are stagnating, and have been for some time. This has corrosive, follow-on effects on the social fabric of nations like France, Italy, and Spain. Further, the EU’s organizational mechanisms have proven inadequate to both the euro monetary crisis and the current refugee crisis, and secession movements (whether from the EU itself, as in “Brexit”, or within EU nations, e.g. Scotland or Catalonia) are likely to strain them even more going forward. Finally, prospects for European adaptation to the 21st century tech economy are dimmer than one would like. Entrenched interests are using the force of government to repress innovation, start-ups are thin on the ground, and major new tech companies—“European Googles”—are nowhere to be seen.

Since the Great Recession, the European members of NATO cut the equivalent of the entire German military budget from their combined defense expenditures. Many of our mainland European allies are also at least somewhat ambivalent about the extent of their commitment to defend other NATO members, particularly the new member-states in the Baltics—a fact that has not escaped Russia’s notice.

More broadly, the international security system promoted by the United States is based on two principles, alliance and deterrence, that greatly amplify our military capacity—and which we have undermined in recent years. Our alliances allow us to do more with less; they also repress competition between our allies. For instance, mutual alliances with America help to keep Japanese-South Korean tensions in check today just as the American presence helped France and Germany establish closer relations based on mutual trust in the past. Deterrence is key to the alliance system and also to minimizing the loss of U.S. lives as we fulfill our commitments around the world.

Recent events in the Middle East demonstrate what happens when alliances fray and deterrence loses its force. Iranian and Russian adventurism across the region has undermined the confidence of American allies and increased the risks of war. American allies, like Saudi Arabia, who fear American abandonment, have grown increasingly insecure. Saudi freelancing in Syria and Yemen may lead to great trouble down the road; Riyadh is not institutionally equipped to take on the burdens it is attempting to shoulder.

Another significant disadvantage facing U.S. policymakers is that the international order is based on institutions (like the UN) that are both cumbersome to work with and difficult to reform. As we get further and further from the circumstances in which many of these institutions were founded, they grow more unwieldy, but for similar reasons, nations who were more powerful then than now grow more deeply opposed to change. The defects of the world’s institutions of governance and cooperation are particularly problematic for an order-building, alliance-minded power like the U.S.

Meanwhile, many of our domestic institutions relating to foreign policy are not well structured for the emerging challenges. From the educational institutions that prepare Americans for careers in international affairs (and that provide basic education about world politics to many more) to large organizations like the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Pentagon, the core institutions on which we need to rely are not well suited to the tasks they face.

In the Cold War era, the challenges were relatively easy to understand, even if developing policies to deal with the threats was often hard. Today, the policy challenges are no less difficult, but the threats themselves are more diverse. A revanchist Russia, competing radical Sunni and Shia jihadist movements, and a rising China all represent important challenges, but they cannot be addressed in the same way or with the same tools. Americans, particularly those in public service but also the engaged citizens whose votes and opinions sway foreign policy, will have to be more nimble and nuanced in their understanding of the problems we’re facing than ever before.

In spite of these serious disadvantages and problems, the United States is much better positioned than any other country to maintain, defend, extend and improve the international system in the 21st century. We should be sober about the tremendous challenges facing us, but we should not be pessimistic. We cannot do everything, and we will not do everything right, but we can be more right, more often than our adversaries.

The United States remains an adaptable society that embraces change, likes innovation, and adjusts to new realities with enthusiasm (and often, an eye to enlightened self-interest). Indeed, in many ways, these truisms are more true now than ever. We remain on the cutting edge of technological development. We’re better suited than our global competitors to weather demographic shifts and absorb new immigrants. And despite significant resistance to change among some segments of society (in particular, ironically, the “public-service” sector), we are already starting to re-engineer our institutions for the 21st century.

One of the United States’ greatest advantages is our exceptional array of natural resources. We possess a tremendous resource base with energy, agriculture, and mineral wealth that can rival any nation on earth. Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal well drilling have fundamentally transformed the American energy landscape overnight. Oil production is up 75 percent since 2008, and new supplies of shale gas have millions of Americans heating their homes cheaply each winter. New U.S. oil production has been a big part of the global fall in oil prices, and shale producers continue to surprise the world with their ability to keep up output, even in a bearish market. In 2014, the U.S. was the world's largest producer of oil and gas, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Energy policy debates have shifted from issues of scarcity to those of abundance: we're now discussing what to do with our bounty. Do we sell LNG abroad? End the ban on crude oil exports? These are good problems to have.

The United States also retains the most advantageous geographical position of any of the world’s great powers. We have friendly, resource-rich neighbors; Canada is a rising power with enormous potential, and Mexico and many other countries in Latin America have made substantial progress. We face both of the world’s great oceans, which allow us to engage in trade while still insulating us from many of the world’s ills.

The United States has an unprecedented network of alliances that gives us unmatched global reach and resilience. The vast majority of the world’s developed nations are U.S. allies. In fact, of the top 50 nations by GDP according to the World Bank, only four—China, Russia, Venezuela, and Iran—are adversaries. Likewise, only two of the top fifteen military spenders are not friendly to the U.S. Largely, we have the kind of friends one hopes to have.

Moreover, the world can see that The United States stands for something more than its own power and wealth. The democratic ideals we honor (even if we do not always succeed in living up to them) resonate far beyond our frontiers. The bedrock belief of American society that every woman and every man possesses an innate and inalienable dignity, and our commitment to ground our institutions and our laws on that truth inspire people around the world. The American creed is one that can be shared by people of all faiths and indeed of no faith; our society’s principles stand on common ground with the world’s great religious and ethical traditions. This American heritage gives us a unique ability to reach out to people in every land and to work together to build a more peaceful and prosperous world.

The United States also has a favorable climate for investment and business that ensures we will remain (if we don’t screw up) a major destination for investment. These factors include: America’s traditional devotion to the rule of law; long, stable constitutional history; excellent credit rating; large internal market; 50 competing states offering a range of investment possibilities; rich science and R&D communities; deep financial markets adept at helping new companies grow; stable energy supplies (likely to be below world costs given the advantages of pipeline gas compared to LNG); and an educated workforce. We’re not at the top of every one of these measures globally, but no country can or likely will match our broad strength across them.

This might not be the most popular thing I’ve ever told a room full of politicians, but one of the biggest ways in which America is fortunate is that, as I’ve written elsewhere, “the ultimate sources of American power – the economic dynamism of its culture, the pro-business tilt of its political system, its secure geographical location, its rich natural resource base and its profound constitutional stability – don’t depend on the whims of political leaders. Thankfully, the American system is often smarter and more capable than the people in office at any given time.”

One way to look at our position is this: at the peak of its global power and influence in the 1870s, the United Kingdom is estimated to have had about nine percent of the global GDP. America’s share today is more than double that—and likely to remain at or close to that level for some time to come.

American power today rests on strong foundations. Those who argue that the United States must accept the inevitability of decline, and that the United States can no longer pursue our global interests do not understand America’s strengths. The United States, in association with its growing and dynamic global alliance system, is better placed than any other country or combination of countries to shape the century that lies before us.

Opportunities & Challenges

The U.S. has several opportunities in the coming years to significantly advance its interests around the world. In Asia, a large group of countries want the same kind of future we do: peaceful, full of opportunities for economic growth, and with no one country dominating the rest. Two generations ago, this was a poor, dictatorship-ridden region; today, it’s full of advanced, high-income economies and contains many more stable democratic states than in the past. The regional response to China’s assertive policies in the East and South China Seas demonstrated that many countries are willing and indeed eager to work with the United States and with each other to preserve the way of life they have created from regional hegemonic threats.

In Europe, despite some quarrels and abrasions, our longstanding allies have worked together to build the kind of zone of democratic, peaceful prosperity that the U.S. hopes the whole world will someday enjoy. But what we’re finding, not for the first time in our history, is that Europe works best when America remains engaged with it. While it’s tempting to think that a bunch of first-world, prosperous democracies can handle their own corner of the world (and perhaps some of the neighboring bits, please?), America is the secret ingredient that keeps this historically contentious, rivalry-ridden area, full of states of differing size and capacity, with different attitudes toward economics, defense, social organization, and much else, working together. When Europe works well, it’s the best advertisement for the American vision to the rest of the world. It offers us the chance to work together with partners who share our belief in rule of law and human rights. And fortunately, the fixes that our relationships with European nations need are relatively cheap, easy, and even pleasant: more time, more engagement, more mutual cooperation.

Perhaps the biggest opportunity in the 21st century is not geopolitical, however, but economic and social. The tech revolution has the potential to boost standards of human happiness and prosperity as much as the Industrial Revolution did. It will likely give our grandchildren a higher standard of living than most of us today can imagine.

We should not underestimate either the extent of this coming transformation, or the enormous power it has to make our lives better. Take, for instance, the environment: 21st-century technology is moving the economy into a more sustainable mode. The information service-driven economy is rising even as the manufacturing economy becomes less environmentally problematic and shrinks as a portion of the total economy. From telework to autonomous cars, innovations are likely to cut down on emissions in the new economy, even while improving standards of living across the world.

The information economy will be more prosperous, more environmentally friendly, and more globally interconnected than what came before it. The U.S. can lead this transition—not by hampering economic growth or by instituting expensive subsidies, but by promoting and accelerating the shift toward a greener but richer and more satisfying economy.

Filled with opportunity as it is, the new century also contains threats: conventional threats like classic geopolitical rivals struggling against the world order favored by the United States and its allies, unconventional threats like terror movements spurred by jihadi ideology, regional crises like the implosion of much of the Middle East and a proliferation of failed and failing states, emerging threats like the danger of cyber war, and systemic problems like the crises in some of the major institutions on which the global order depends -- NATO, the EU, and the UN for example. The United States government itself is not exempt from this problem; whether one looks at the Pentagon, the Department of Homeland Security or the State Department one sees organizations seeking to carry out 21st-century missions with 20th or even 19th-century bureaucratic structures and practices.

Additionally, the United States faces a challenge of strategy. While the United States has enough resources to advance its vital interests in world affairs, it does not have the money, the military power, the know how or the willpower to address every problem, intervene in every dispute, or to dissipate its energies in futile pursuits.

The United States faces an array of conventional and unconventional threats, as well as several systemic dangers. Our three principal conventional challengers are China, Russia, and Iran. All aim to revise the current global geopolitical order to some extent. In the years to come, we must expect that revisionist powers will continue to challenge the existing status quo in various ways. Moreover, the continuing development of “second generation” nuclear weapons states like Pakistan ensures that geopolitical competition between regional powers can trigger global crises.

Meanwhile, we are also confronted by an array of unconventional threats. Despite the fondest hopes of many Americans, Sunni jihadism has not proven to be a passing phase or fringe movement. Al-Qaeda was more resourceful and ambitious than the previous generation of radical salafi groups; its Mesopotamian offshoot (AQIM) was still more effective; today, ISIS has leaped ahead to develop capabilities and nourish ambitions that earlier jihadi groups saw only in their dreams. Unfortunately, the radical movements have lost inhibitions as they gained capacities. Wholesale slaughter, enslavement, barbaric and spectacular forms of execution: these testify to a movement that becomes more depraved, more lost in the pornography of violence, even as it acquires more resources and more fighters. This movement could become significantly more dangerous before it begins to burn out.

Yet radical jihadis may well prove to be less of a threat than the emerging dangers of the cybersphere. Cyber conflict is a new arena of action, one in which non-state, quasi-state and state actors are all present. With almost every day bringing stories of utterly lamentable failures of American cyber security, it must be clearly said that the U.S. government has allowed itself to be made into a global laughingstock even as some of our most vital national security (and corporate and personal) information is captured by adversaries with, apparently, impunity.

But problems like these are pinpricks compared to the damage that cyber war can cause. Not only can industrial sabotage disrupt vital systems, including military command and control systems as well as, for example, the utilities on which millions of Americans depend for their daily necessities, cyberwar can be waged anonymously. Threats of retaliation lose their deterrent power when the attacker is unknown. Worse, the potential for destabilizing first strikes by cyber attacks will complicate the delicate balance of terror, and leaders could find themselves propelled into conflict. Cyber war could accelerate the diplomatic timetable of the 21st century much as railroad schedules and mobilization timetables forced the hands of diplomats in 1914.

Beyond that, one can dimly grasp the possibility of biologically based weapons as a new frontier in human conflict. It is far too soon to know what these will be like or how they will be used; nevertheless one must postulate the steady arrival of new kinds of weapons, both offensive and defensive, as the acceleration of human scientific understanding gives us greater access to the wonders of the life sciences.

Finally, there are systemic or generic threats, which is to say, dangers that are not created by hostile design, but emerge as byproducts from existing and otherwise benign trends that are likely to pose significant challenges to the United States’ interests and security in coming decades. We do not usually think of these as security problems, but they can create or exacerbate security threats and they can degrade our abilities to respond effectively.

For all its promise, the tech revolution entails an accelerating rate of change in human communities that has destabilizing effects. In the U.S., and especially in Europe, these take the relatively benign, but still problematic, form of the breakdown of what I have called the “blue social model”—a tightly integrated economic-social model built during the 21st century that linked lifetime employment and fixed pensions into a socio-economic safety net. Now, the structures that were designed to secure prosperity and economic safety in the 20th century are often constraining it in the 21st.

But elsewhere, the strains of the modern economy may yet be worse, and produce more malign results. In the Middle East and North Africa, government institutions and systems of belief are overwhelmed by the onslaught of modernity. For better or worse, the pressures of modernity will increase on societies all around the world as we move deeper into the 21st century. To date, the United States has demonstrated very little ability to help failed or failing states find their feet. Failing states provide a fertile environment for ethnic and religious conflict, the rise of terrorist ideologies, and mass migration. The United States will need to be ready to deal with the fallout – fallout that in some cases could be more than metaphorical.

Finally, the United States and its allies must recognize and overcome a crisis of confidence. The West’s indecision, weak responses, mirror imaging of strategic competitors who do not share our values, and our tendency to rely upon process-oriented “solutions” in the face of growing, violent threats have encouraged a paradox: our enemies and challengers have become more emboldened, and disruptive to the world order, exploiting the opportunities that the open order supported by the United States and its allies provides.

Western societies have turned inward, susceptible to “there’s nothing we can do” and “it’s not our problem” political rhetoric. As history shows, the combination can carry a very high cost and take many years to unwind. Grand strategy has to take this into account: American leadership is critical to highlighting and thwarting problems that may fester into major global threats. Even the best strategic planning and the best procurement of equipment to meet serious strategic threats is insufficient should current Western leaders lack the wit to recognize and the will to meet challenges as they arise.

Recommendations

What can the United States Congress and the armed services do to prepare the country for the strategic challenges of the future? The Committee invited me to look beyond the day to day problems and to take a longer view. Here are some thoughts:

1. Invest in the future.

The apparently inexorable acceleration of technological and social change has many implications for the armed services of the United States. It is not just that weapons and weapon platforms must change with the times, and that we must continue to invest in the research and development that will enable the United States to field the most advanced and effective forces in the world. Technological change drives social change, and conflict is above all a social activity. Military forces must develop new ways of organizing themselves, learn to operate in different dimensions, understand rapidly-changing cultural and political forces and generally remain innovative and outward focused.

New tech does not just mean new equipment on the battlefield. As tech moves into civil life, the structure of societies change. Insurgencies mutate as new forms of communication and social organization transform the ways that people interact and communicate.

The need for flexibility is heightened by the diversity of the world in which the Armed Forces of the United States, given our country’s global interests, must operate. American forces must be ready to work with Nigerian allies against Boko Haram, maintain a base presence in Okinawa while minimizing friction with the locals, operate effectively in the institutional and bureaucratic culture of the European alliance system, while killing ruthless enemies in the world’s badlands. Our combat troops must work in a high tech electronic battlefield of the utmost sophistication even as they work to win the hearts and minds of illiterate villagers.

The armed services must continue to reinvent themselves to fit changing times and changing missions, and they must be given the resources and the flexibility necessary to evolve with the world around them. The bureaucratic routines of Pentagon business as usual will be poorly adapted the kind of world that is growing up around us. A focus on re-imagining and re-engineering bureaucratic institutions is part of investing in the future. Private business has often moved more quickly than government bureaucracy to develop new staffing and management patterns for a more flexible and rapidly changing environment. Government generally, and the Pentagon in particular, will need aggressive prodding from Congress to adapt new methods of management and organization. Investment in better management and organizational reform will be vital.

2. Address the interstitial spaces and the invisible realms.

The United States, like Great Britain, is a power that flourishes in the ‘spaces between’. In the 18th century, think of sea power and the world markets that sea power guaranteed. Britain rose to world power by mastering the ‘spaces between’ the world’s major economic zones. In the 19th century Britain added telegraph and cable communications to its portfolio, developing and defending the world’s most extensive network of instantaneous communications. Similarly, the British build a global financial system around the gold standard, the pound, and the Bank of England. Again, the focus was less on dominating and ruling large land masses than on facilitating trade, communications and investment among them.

In the 20th century, the nature of this space changed again: air power, radio and television broadcasting, satellites and, in the century’s closing years, the internet created new zones of communication. The United States was able to retain a unique place in world affairs in large part because it moved quickly and effectively to gain a commanding position in the development and civil and military use of these forms of communication. Whether it is the movement of goods or of information or of both, Anglo-American power for more than three centuries has been less about controlling large theaters of land than about securing and expediting trade and communication in the ‘spaces between’.

This type of power, most evidently present today in the world of cyberspace, remains key not only to American power but to prosperity and security in the world. Information is becoming the decisive building block of both economic and military power.

American defense policy must remain riveted on the developments in communications and information processing that are creating the contemporary equivalent of the sea lanes of the 18th century and the cable lines of the 19th. The recent series of high profile hacker attacks against key American government and corporate targets suggests that we have lost ground in one of the most vital arenas of international competition.

This needs to change; cyber security is national security today and at the moment, we don’t have it.

3. Establish a Congressional Office of Strategic Assessment.

In order to perform its oversight functions more effectively, the Congress should consider establishing a professional, nonpartisan agency that can be a source for independent strategic research and advice, and which can evaluate executive branch policies in a more systematic and thorough way than current resources allow. Similar in some ways to the CBO, a COSA would provide in-depth analysis and other resources to members and staff. Such an office would ideally be able to analyze anything from the strategic consequences of a given trade agreement to the utility of a proposed weapons system. This office would also allow a much more sustained and effective form of Congressional oversight, restoring a better balance to the relationship between the Executive and Legislative branches of government.

The intersection of military, political, social, technological and economic issues in our world is constantly creating a more complex environment for both military and political strategic policy and thought. Even the most dedicated members with the hardest working staff cannot fully keep up with the range of problems around the world and their impact on American interests and policy. Yet effective Congressional oversight is necessary if the American system of government is to reach its full potential in the vital field of national security policy.

A non-partisan office under Congressional control that had a strong staff and the ability to engage the best minds in the country on questions of national strategy would help Congress fulfill its responsibilities in this new and challenging environment.