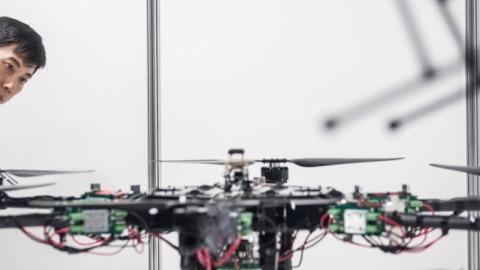

Some technology experts are calling 2015 "Year One of the Era of the Drone" in Japan, and no wonder.

Japanese companies have always been at the forefront of new technologies, and the commercial production of drones could be a multibillion yen industry. Certainly that is the hope of the 50-plus companies that took part in Japan's first International Drone Expo held just outside of Tokyo recently.

All that is needed is some sensible legislation and consistent regulation, which the Japanese Diet is working on, for this new sector of Japan's high-tech industry to take off -- literally.

However, this is one instance where looking to the U.S., where the drone market is projected to generate $80 billion over the next ten years, is not going to help.

The U.S. is of course the technological leader in the militarized use of drones, or UAVs, as the U.S. Air Force prefers to call them. But in the civilian sector, the government's efforts to keep up with the rapidly expanding demand for commercial drones has lagged far behind.

Legislation with absurd results

A single government agency, the Federal Aviation Administration, is the regulator for anything that flies through the skies, and since 2007 it has threatened to prosecute anyone who uses a drone for commercial purposes. Only recreational, low-flying drones, such as children's remote-controlled helicopters, are exempt.

The absurd result is that U.S. companies, such as Amazon and Google, will be using drones for delivery and other uses in places like Australia and Europe before they are ever allows to employ the same technology at home.

In 2010, Congress ordered the FAA to come up with new rules for the commercial use of drones by this year. The FAA bureaucrats have said they will not be able to meet the deadline.

Japan can do better.

Indeed, some U.S. businesses point to Japan's use of agriculture drones as an example of how useful and safe commercial drones can be. Japan has used drones since the 1980s to spray pesticides on 40% of the country's rice crops. Ironically, the recent crash landing of a drone carrying radioactive material on the prime minister's house has convinced some Japanese that this is a technology in need of very tight regulation -- possibly even an outright ban.

Myriad uses

The fact is, the opportunities for unmanned aerial technology in Japan are enormous and not only for commercial use such as deliveries. A 2-3kg drone can carry loads of up to 10kg and will soon be able to deliver packages of up to 30kg. Drones can be invaluable in dealing with security and environmental challenges, such as monitoring radiation leaks after the Fukushima disaster, or unobtrusively keeping close tabs on security at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Indeed, some have proposed creating the first "drone zone" in and around Fukushima to test existing drone technologies and the next generation of flying robots.

This could propel Japan to the forefront of the international drone industry. Kenzo Nonami, engineer and CEO of Autonomous Control Systems Lab in Chiba, for example, has unveiled technology that flies autonomously without GPS, but generates its own maps with a laser scanner instead.

Drones with such capabilities could fly in tunnels and under bridges, where GPS signals are blocked, to carry out important safety inspections that are out of reach for humans. Meanwhile, advances in artificial intelligence applications will enable drones to avoid banned areas such as military bases and public buildings. Drones will also be able to detect their own malfunctions before they happen.

Of course, there is public concern about drones, especially large ones, malfunctioning and crashing. But in fact, drones have better flight stability than airplanes or helicopters. The effect of manned aircraft crashing and malfunctioning, including through pilot error, is far worse than it is for drones. A robot instead of a pilot in the cockpit of Malaysia Airlines 370 or Germanwings 9525 could have prevented massive human tragedy.

Singapore's drone laws

In the meantime, a good place to look for new drone rules for Japan might be Singapore, where a bill amending its Air Navigation Act and Public Order Act came into effect at the start of this month.

The rules open up the skies to drones, but with some intelligent and very basic regulations which not only Japan, but also the U.S., could well study.

For example, the rules ban the carrying of all dangerous substances, such as radioactive material, and a specific permit is needed to drop or discharge anything from a drone.

Unmanned flights over special events and public buildings also require a permit, but otherwise it is legal to fly drones in urban areas and along roads (this is currently banned in Japan).

Operators must also register and have a permit to fly any drone larger than 7kg. Permission is also needed to operate drones within 5km of an airport regardless of altitude, or above 61 meters and 10km from an airport.

All applications to operate drones pass through Singapore's Civil Aviation Authority's online system, so customers have to deal with only one government agency regardless of the kind of permit they need.

It is true Singapore's rules do not address privacy concerns -- always a worry when confronting this potentially intrusive technology. On the other hand, other laws can be invoked so a drone buzzing over someone's home is treated as illegal trespass, or taking photos or videos of people in public without their permission is harassment. Under Singaporean law, a drone photographing a woman in a state of undress without her knowledge is treated as an insult to her modesty, which is a punishable crime. It's not clear how Japanese courts will handle that issue -- or U.S. courts, for that matter.

These rules would mark a big change from Japan's largely regulation-free environment. But in an age of lone-wolf terrorists, not to mention psychopaths with engineering degrees, "Year One of the Era of the Drone" cannot afford too cautious a start -- nor, if safely regulated, can Japan wind up with too many drones.