President Trump made many promises on the campaign trail, including one to greatly increase the size of the Navy. However, there is a “say/do” contradiction at work between Trump and expansion of American Seapower, one that manifests itself in his view of the role of the U.S. in the world, his key personnel choices, his view of the Russia threat, and his notable lack of public leadership necessary to build support for a larger fleet.

The Campaign

The centerpiece of candidate Trump’s call to rebuild American military power was his call for a 350-ship fleet built around 12 nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. The Trump fleet represented an increase in size of over 25% compared to the 276 ships in the fleet on Election Day and was fully 15% larger than the 308 ships called for in the final Obama fleet plan. He distinguished himself among GOP hopefuls in calling for a larger fleet, as both Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio were similarly inclined. Trump’s victory in November caused a great deal of anticipation among Seapower advocates who consistently called for a larger fleet, giving the Navy political cover necessary to release its December 2016 Force Structure Assessment calling for 355 ships, an increase of 47 ships from its 2012 review (which had been the basis for the 308-ship fleet).

There was little in the way of a strategic narrative to support an increase in fleet size in Trump’s campaign rhetoric, and given the much-reported lack of policy staff preparation within the campaign, there is little reason to believe such justification existed. Additionally, given candidate Trump’s positional flexibility and propensity to make things up on the fly, it was difficult to discern where a naval buildup fell among the many promises he made on the campaign trail, or even whether it was important to him at all. Nevertheless, as 2017 dawned, a President came to office who ran on a larger fleet, the Navy had promulgated its larger (355 ships) fleet force structure, and three Congressionally mandated fleet architecture studies reached the consensus view that the Navy’s planned fleet of 308 ships was insufficient. All the cosmic tumblers were clicking into place to support a significant fleet buildup.

Nearly a year later, there is little evidence to suggest that a fleet expansion beyond the Obama Administration’s number is underway, or under serious consideration. A careful reconsideration of facts in evidence leads to the conclusion that at best, the “350-Ship Navy” claim was a meaningless campaign promise, and at worst, was an opportunistic lie deeply at odds with the rare ideological underpinnings Trump possesses.

Seapower and Globalism

Globalism, and the expansion of free trade that underpins it is responsible for much of the growth of the global economy in the past quarter-century, as well as the dramatic decline in world poverty. The fall of the Warsaw Pact was the precipitating security event that contributed to this economic dynamism, but global freedom of the seas, over which most international trade travels, is what has kept the party going, freedom provided by a preponderant United States Navy. In fact, protecting global freedom of the seas is the most important mission of the U.S. Navy, mostly because no other element of military power has even a minor role in providing it, and how utterly dependent our prosperity is upon it. America is an outward-facing trading nation that still possesses the world’s largest and most vibrant economy. Our prosperity is directly tied to global free trade, and global free trade depends on freedom of the seas. There is only one Navy on Earth with the forces and basing structure to act as the global guarantor of freedom of the seas, and it does so because the nation’s economy and security demand it. Others prosper because of global trade carried over free and open seas, but no nation prospers more than we. Our future prosperity could be at risk without free and open seas, and no nation has a greater interest in guaranteeing them.

Sir Walter Raleigh’s dictum that “…whosoever commands the sea commands the trade; whosoever commands the trade of the world commands the riches of the world, and consequently the world itself” has animated America’s naval strategy since World War II, although it has done so in a manner enriching the entire world. That strategy is under increasing pressure, and nowhere more so than in the South China Sea, where China’s naval and missile buildup is designed to challenge America’s ability to provide unimpeded movement for its commerce and that of others, enabling China to exercise de facto dominance over a region of great importance to the United States.

Finally, the U.S. Navy’s global posture provides the catalytic spark for U.S. led regional security in areas where our interests are most notable, and most threatened. Because the U.S. Navy is strong and forward deployed, smaller, less powerful nations are incentivized to join with us in cooperative maritime security efforts and can do so without fear of retribution from other powerful, regional actors (see China, Russia, Iran). Were the U.S. Navy less forward and less strong, regional powers could exert more pressure on these weaker nations resulting potentially in either destabilizing arms races or painful accommodation of the regional power in ways antithetical to our security interests. In other words, it is in our interest to be there, and it is in these lesser powers’ interest to be there with us.

What Trump Believes

Donald Trump’s political views have been flexible over the years. He has been both pro-life and pro-choice. He has been a gun-control supporter and guardian of the second amendment. He has been stridently anti-immigrant while stocking his resorts with foreign guest workers. Some of Trump’s supporters believe that this positional flexibility is a good thing, which the lack of ideological moorings leaves him free to “make deals.” And while the record is clear that Trump does not have many deeply held principles underlying his politics, one consistently held and vocally expressed strain of thought is that the United States is overextended, that allies are not paying their share, and more recently, that free trade often works against American interests. By way of evidence are two articles covering Trump nearly thirty years apart. The first was a recent piece looking back on a younger Donald Trump who took out a full-page advertisement in the Washington Post, The New York Times, and the Boston Globe on September 2, 1987. Here is how a portion of it went:

“For decades, Japan and other nations have been taking advantage of the United States… "The saga continues unabated as we defend the Persian Gulf, an area of only marginal significance to the United States for its oil supplies, but one upon which Japan and others are almost totally dependent….why are these nations not paying the United States for the human lives and billions of dollars we are losing to protect their interests…the world is laughing at America's politicians as we protect ships we don't own, carrying oil we don't need, destined for allies who won't help."

Nearly thirty years later while running for President, Trump said the following during a campaign speech in April 2016:

“Secondly, our allies are not paying their fair share, and I’ve been talking about this recently a lot. Our allies must contribute toward their financial, political, and human costs, have to do it, of our tremendous security burden. But many of them are simply not doing so. They look at the United States as weak and forgiving and feel no obligation to honor their agreements with us. In NATO, for instance, only 4 of 28 other member countries besides America, are spending the minimum required 2 percent of GDP on defense. We have spent trillions of dollars over time on planes, missiles, ships, equipment, building up our military to provide a strong defense for Europe and Asia. The countries we are defending must pay for the cost of this defense, and if not, the U.S. must be prepared to let these countries defend themselves. We have no choice.”

Thirty years apart, these statements bespeak the consistent view of a man with little understanding of how much the United States benefits economically from its forward-deployed military posture, and even less of an understanding of the choices those nations face in their regional security environments especially were we to abandon our alliances. Additionally, given that a naval expansion on the order of what he promised on the campaign trail would cost upwards of $40B a year in total costs, it begs credulity to believe that he would advocate doing so given the laggard performance of our friends and allies in paying for their own defense. If the Administration does begin to assert the need for a larger fleet, Congress must require it to explain the role of this dramatically expanded force, in light of the President’s clear disdain for forward operations.

The Russia Question

The Navy’s 355 Ship Force Structure assessment and each of the three congressionally-mandated fleet architecture studies shared an underlying threat assumption that contributed to their broad consensus on force levels. That assumption was that Russia posed a significant and growing threat to our interests in the North Atlantic, the Norwegian Sea, the Baltic Sea, and the Eastern Mediterranean. In fact, in the CSBA study in which I participated, we considered the Russian threat to be more serious in the near term than the China threat, and our recommended naval force posture reflected it (see pp. 53-59)

Putting aside for the moment ongoing questions of Russian meddling in the 2016 Election and potential Trump campaign collusion therein, it is not at all clear the degree to which President Trump views Russia as a military threat to American interests. If Russia is not a threat, the Navy likely does not have to be 350 ships. If Russia is a threat requiring a Navy that large, the President should be required to say so—something he has not authoritatively done, but which would have to be made clear in a coherent justification for a naval buildup. The impending release of the Trump Administration National Security (NSS) Strategy should provide some indication of what the President believes, but Congress should not rely solely upon the NSS. It should insist that the President name a resurgent Russia as a clear national security threat to the United States and that the threat warrants additional buildup in U.S. forces.

Personnel is Policy

Perhaps the most obvious sign of Trump’s less than arduous attachment to his promise to grow the fleet was his selection of former South Carolina Congressman Mick Mulvaney (R-SC) as his Director of Management and Budget. Originally elected with the Tea Party Class of 2010, Mulvaney earned a reputation for opposing the more hawkish elements of the GOP in the House. Clearly, Mulvaney works for the President and will carry out the President’s wishes, but in the absence of Presidential leadership, Mulvaney will be an unlikely supporter of increasing the size of the Navy. In fact, the original FY 18 budget submission to Capitol Hill in the spring of 2017 accounted for no additional ships above what the Obama Administration had planned for that year. A furor from the Alabama and Wisconsin Congressional delegations added a second Littoral Combat Ship to the budget—presumably against Mulvaney’s wishes.

The selection of retired Marine General James Mattis as Secretary of Defense has also put a chill over the warm talk of naval expansion, as one of his initial acts upon taking office was to issue budget guidance that made growing the force his third priority, behind current readiness and replenishing weapons stocks, and that more detailed plans for force growth would be held in abeyance pending the White House issuance of a National Security Strategy and the Defense Department’s submittal of a National Defense Strategy—neither of which is expected until early next year. It is difficult indeed to find anything other than generalized statements of support for a larger Navy from Mattis, a situation of some irony given his propensity as the U.S. Central Commander to demand the near-continuous presence of two aircraft carriers.

Finally, the only evidence we have thus far of the top-line management of the Department of Defense budget is the President’s 2018 Budget Submission, which represented only a 3% increase over the Obama projection for 2018. Three percent does not a massive military buildup make.

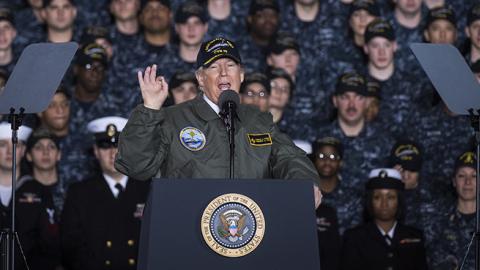

Presidential Leadership

The final evidence offered for the lack of priority afforded a naval buildup under President Trump is that he has done almost nothing to make it happen, and historically speaking, nothing is as important to growing a Navy as Presidential support. As stated earlier—building a larger Navy is an expensive proposition, and while Congress appears ready to provide the Navy with more resources, it will not do so in the absence of a clear plan of how that money will be spent and the sense that the President is dedicated to following through on it. A campaign promise is insufficient reason for the expense. A clearly articulated, consistently reinforced statement of need is central to the persuasive case that must be made for the American people to allocate massive resources in peacetime to a naval building program. That case has not been made, and the President must be the one to make it. Thus far in his Presidency, we have not seen active Presidential support for policies the President was believed to be personally invested in (see Health Care, tax reform), so it remains to be seen whether he will muster the effort to get behind a larger Navy.

Is All Hope Lost?

Given the conflict between the benefits of dominant American Seapower and the consistency of Donald Trump’s most long-standing national security belief, the dubious nature of the President’s view of the Russian threat, his appointment of senior subordinates not likely to be committed naval expansionists, and his own lack of leadership on the issue—the 350 ship Navy appears to be just another broken campaign promise.

The way forward is clear; Congress must assume a greater share of the lead in moving forward with a naval expansion. Uniformed Navy leadership must step forward and relentlessly reinforce the strategic benefits conferred by preponderant American Seapower. For the first time in its history, the nation must attempt to increase the size of its Navy in the absence of Presidential leadership or attention.