Following is the full transcript of the February 28th, 2019 Hudson event titled Marijuana, Mental Illness, and Violence: A Conversation with Alex Berenson.

JOHN WALTERS: Welcome to the Stern Policy Center here at Hudson Institute. I am John Walters. I am Hudson's chief operating officer, and I also co-direct our Center on Substance Abuse Policy Research. I want to send a special welcome to those of you who are joining us from C-SPAN and those online who are watching on this important topic. We are very pleased and honored to be joined by Alex Berenson, whose new book, marijuana - on marijuana, "Tell Your Children: The Truth About Marijuana, Mental Illness And Violence," has gotten an awful lot of attention, and it deserves even more. We've got copies available for someone who'd want to purchase it, and Alex has graciously agreed to sign some books after this event. So if you want to get a copy or get a copy to send to someone you know who should read it, you're welcome and encouraged to do so.

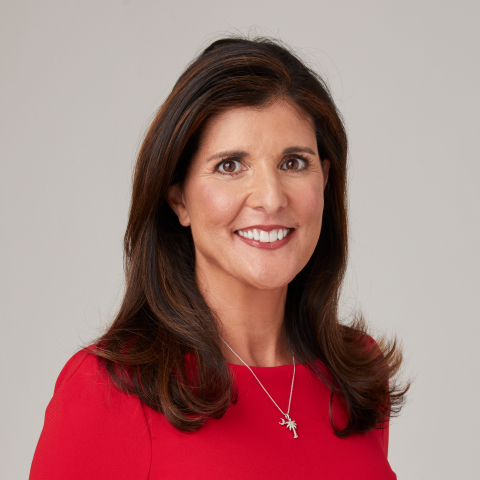

You have a sheet with Alex's bio. Let me briefly summarize that by saying he's a gifted young man, graduated from Yale, became a successful journalist, was a writer for The New York Times, did coverage in Iraq, did Hurricane Katrina, has then turned to a very successful, right out of the blocks, career as a novelist, won an award for his first novel, and went on and has continued in a very successful career as a writer-journalist. Then I thought maybe we'd start off by you explaining - he made a decision to write this book, which caused him to become vilified, his life threatened, so he has a, like, little "Breaking Bad" story here. And I thought I'd let him maybe start out by kind of explaining what happened, what went wrong and what went right here.

ALEX BERENSON: So thank you, John. Thank you so much for having me. So I - as I mentioned in the book, I decided to write this a couple of years ago, after my wife - who's a forensic psychiatrist, and she deals with the criminally mentally ill - and I had one too many conversations where she told me that somebody she was evaluating had committed some horrendous crime under the influence of cannabis. And I told her, really? Wasn't, you know - wasn't some other drug involved? And that sounds like "Reefer Madness" to me. And she told me, you know, go read the studies. And you know, she is the one who trained at Harvard and Columbia. She's the one who sees these patients. Of course, she knew exactly what she was talking about. And so the book, in some ways - I was an investigative reporter for The Times - was pretty easy to write, at least parts of it, in that I was - I had the National Academy of Medicine to draw on. I had dozens of studies published in top peer-reviewed journals to draw on.

The science seemed clear and unequivocal to me, and I had, you know, scientists - clinician-scientists, researchers from all over the world who were willing to talk to me. And you know, and when I asked them about correlation and causation, they said, well, here's, you know, here's how we tease that out. And so to some extent, the book part - the more interesting part of the book for me, as a reporter, was how did we get here? How do we get to a point where the scientific community has a broad consensus about the - certainly, the psychiatric community has a broad consensus about this. And yet, the public perception about cannabis has gone the other way in the last 20 to 30 years, in such a shocking way that we're now on the verge of legalizing this drug nationally in the United States. And you know, and the legalization community likes to pretend, oh, well, the U.S. is sort of an outlier here. We're so much more conservative. In fact, we are an outlier. We're much, much more liberal than almost any other country, you know, with the exception of Canada and Uruguay. You know, so that was what the book - I mean, that's not what the book is mainly about, but to me, that was in some ways the more interesting question as an investigative reporter.

And the response to the book has been a master class for me in how we got here, and by the way, in how the opioid epidemic got to the place it is now because journalists seem - I mean, there's a massive failure of journalism around cannabis. And in general, despite what we've seen with opioids, despite what we've seen with cigarettes, people seem to be unable to get it through their heads that the manufacturers of addictive products cannot be trusted to tell the truth about the risks of those products. It's beyond me. And so, you know, the skepticism that, as a Times reporter, I displayed about the drug industry, the pharmaceutical drug industry, is completely lacking from the coverage of marijuana in the United States.

WALTERS: I was struck, though, that you, unlike some of the other people working this field - and I did some of this as a government official on the outside - you have, through the power of this book, spoken to people - I've read reviews in National Review, read a review in The American Conservative and a review in Mother Jones. I mean, this is kind of a span you don't see very often, of people saying, you know, I may disagree with some of this or that, but this is very, very shocking, and this is something we need to pay attention to. Say a little bit about how you - how - some of this argument, for those of you who don't follow this issue or have not yet read your book - and I do recommend that you do it because, aside from all the other things, as somebody who's written on this stuff, it's extremely hard to make data something you want to read because it's, like, pages and numbers and everything else, and you've done a beautiful job - you're obviously a great writer - of taking both individual examples, but also taking the larger context of the studies and making their points clear and readable.

But tell me what if - you started out as you arguing with your spouse, and you know, I've learned the hard way, too, don't fight because you're going to lose. So your wife is right, and then you find out that your attitude, which was probably the attitude of most Americans today, you know, feel that, you know - we've embedded in this that "Reefer Madness" is the subject of the day, when people are on the wrong side of cannabis. Tell me what you saw and what - how you found the arguments of the book to be most powerful because you're making this argument now on a regular basis.

BERENSON: So I think the book builds, you know. And I do think my experience as a novelist helped me. There's a couple of points on that. One is that my very first book was a nonfiction book called "The Number," which is about the accounting scandals of the - really of the entire 20th century, but especially in the '90s. And you know, it's a fine book. It came out the week the war started, the Iraq War in 2003, and was completely ignored. And somebody I know, an editor I know, said, well, you know, it's a nice book, but there's not very many people in it, and people like to read about people and - which is a lesson that I never forgot. And so I tried to find ways to tell this story through the scientists, and you know, and even have some vignettes about them and who these people are, because a lot of them are pretty interesting people. And so - and at the same time, I tried to show that we've known this on some level for a long time.

So the book - you know, the book starts more than 100 years ago, and it sort of focuses on what was going on in Indian psychiatric hospitals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and there's a fascinating scientist, who's long dead, who I would, you know, love to, you know, have a dinner with that guy in 1900 and see what he had to say about this because it is so much on point with what psychiatrists in psychiatric hospitals see today. And so - and then the book sort of builds, and once you have an idea that I'm not just going off and telling you "Reefer Madness," here's - you know, here's where you can depend on me to explain the science. Then I get into here's some personal stories of people who've been affected by this. And then my joke about this is, come for the science, stay for the true crime - the third section of the book is about these horrible, horrible cases of psychosis-induced violence that often, or in this book, always have a cannabis component to them. And you know, I was fortunate. I - you know, one of the people who committed one of these murders was willing to talk to me. And you know, I got some very good, very comprehensive data on - you know, details on some other cases. And so, you know, in drawing, I guess, a little bit on my experience as a novelist in the last 10 years, I put that together in a way that I hope is interesting to people. And you know, the legalization community hates the book. The for-profit companies, you know, in the industry hate the book because I think it does dramatize this in a way that kind of grabs you by the throat, where even if you think the science - even if you think that I've overstated the strength of the science, I don't see how you read this book and don't at least say, this is an issue that needs to be seriously considered.

WALTERS: Yeah, part of the rhetorical problem you have is that the gap between what the science is showing you, and even, as you say, on the violence part, the evidence for the relation to violence is all around us, and we don't see it. So the problem is not ignorance; the problem is willful closing of the eyes and unwilling to embrace that. And I wondered now that you've done the book, and you've thought about this, you've thought about the task of making this argument for the book, but also as you talk about the book, why are we willfully blind on this?

BERENSON: Well, because the media has not done its job for the last 20 years. And there's a - there was a study actually that came out this month showing how coverage of cannabis has changed in The New York Times in the last 20 years and how that change is directly - not just correlated but essentially leads the change in public attitude. So most people don't use cannabis. You know, half the country's never used it. Even in 2017, only 15 percent of people have used it even once. Use is very heavily concentrated in a small group of people who use every day, you know, who love the drug, a lot of whom consider it medicine, which is a whole 'nother issue we can talk about. But most people don't use. And most Americans - so they're depending on the media to tell them, is this safe? Is this dangerous? Oh, it's safe. You know, The New Yorker is going to run an article about THC-infused, you know, food at a dinner party.

The Times is going to have a Styles piece about how, you know, I gave CBD to my dog. These really absurd stories that would not be written about any other intoxicant - much less, you know, a drug with severe psychiatric side effects - are presented without question. The Washington Post had a story last year - I don't know if it was on the op-ed page; it was not on the op-ed page. But it was effectively an opinion piece from a woman in Vermont who was talking about mothering on cannabis and how it made her a better parent. Well, you know, The Washington Post might want to look at the statistics from Florida and Texas and Arizona that show that, in a third of all child deaths, the parents are cannabis users. And that's more than any other drug. It's more than alcohol. This is an epidemic that has been not just ignored by the media but papered over.

WALTERS: Yeah. The other thing is, I think the - both the psychiatric threat of cannabis has not been fully appreciated despite the studies but also the violence. I want to go back to that a bit because you also point out - there are some very prominent and horrifying national stories that involve cannabis, but that's not considered. Could you say a little bit about that?

BERENSON: Well, so there are there are many, many cases in which cannabis is linked to violence.

WALTERS: And this is, by the way, the point you make which most infuriates the people on the other side. They're willing to say, well, OK, there's some psychological stuff. They don't want to go as far. But when you made the violence - when I read reactions to this from the critics, when you make the violence argument, they stop thinking and just go into a rage.

BERENSON: Which is ironic.

WALTERS: Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

BERENSON: You should follow my Twitter feed to see peace - you know, blissful cannabis fans telling me that I should get shot in the face - no joke. By the way, I would disagree with you. I think the drug advocacy, the drug policy - whatever you want to call them, the drug advocacy community or the drug policy reform community is not honest about the psychiatric risks at all. They severely downplay them. But - so once you understand that schizophrenia is a major driver of violence, not just in the United States but everywhere - and again, I'm not going to say - obviously, most murders and most violent crime are not committed by people with schizophrenia. But they are very disproportionately likely to commit violence. And once you understand that people with psychosis make up a, you know, significant minority of the people in U.S. prisons and you know that, you know, people with schizophrenia are 20 times as likely to commit homicides as healthy people and that that risk is mediated by drug use. In other words, once your - if you're taking your antipsychotics, if you're taking care of yourself, you're not that much more likely to get violent than a healthy person is. But once you're off your meds and you're using drugs, your violence risk is off the charts.

And actually, the highest risk of all is in people who are sort of suffering a first break that are undiagnosed. And you know, young men especially who - you know, these are the people who go home and slaughter their families when they're on break from college. You know, it's in these terrible cases. So once you realize that cannabis does cause psychosis, even the advocates cannot dispute that it causes temporary psychosis. And you know, and I - the evidence is extremely strong that it can cause permanent psychosis in some minority of people. And once you know that psychosis is so directly linked to violence and that that link is mediated through drug use, I think the question becomes not - is this true? - but - how big a fraction of the violence in the United States - the severe violence, the homicides and aggravated assault - is cannabis actually responsible for? And secondarily, there's a huge amount of violence around cannabis dealing, which the police and authorities now are increasingly taking note of and publicizing it. And the idea that this is related to the fact that it's prohibited doesn't seem to be true actually because even in states like California and Colorado, where cameras is now legal, there remains a significant amount of violence if not more than there was a few years ago. And by the way, opioids - you know, we know cocaine can, you know, can produce psychosis in some people, certainly when they use it a lot. We know methamphetamine can.

There's certainly violence around dealing and trafficking in those drugs. Nobody says - A, nobody says those drugs are not linked to violence, as people insist must not be true for cannabis, but, B, there's actually considerably more violence around cannabis dealing than the stimulants. And opiate dealing, for whatever reason, there's actually very little violence around. Maybe it's - you know, it's because people are just too desperate to get the drug. Although, that would seem to cut the other way. For whatever reason, cannabis dealing is linked to a massive amount of violence. And I personally believe, although we don't have evidence to prove this yet, that I think, you know, the fact that it produces low-grade paranoia in many users, paranoia that does not rise to the level of psychosis, probably helps fuel that violence.

WALTERS: Let me ask you a little bit about the research that you talked about in some detail about that - when you look at some of the smaller studies that have been done carefully, longitudinal studies over a number of years, it's very hard to do these in large populations like the United States because it's hard to keep track of people. So you've gone to smaller countries and smaller places to try to get the actual phenomenon itself identified and isolated. Tell me a little bit about what you found with regard to the amount of time it takes. And we've talked about some of these phenomena. They're not instantaneous. That's one of the things. It's not like, well, this is a poison that you take, and you get sick right away. And one of the problems in kind of appreciating the risk is that delay minimizes the risk, and there's multiple things going on, so people can easily be confused or be in denial. What did you find, and what's the - what's your guess as to how long the - an increase in intensity and use takes to manifest its full harm?

BERENSON: So that's a really good question, and I think we don't know yet for a couple of reasons. First of all, the cannabis that's being used in the United States, I mean, near pure THC extracts that are being used in the United States, this is a scientific experiment on the human brain that is almost without parallel. We have data, you know, from the '60s and '70s and '80s and '90s, but that cannabis was much less potent. Now, again, listen, if people really wanted to ingest a lot of THC, to smoke a lot of THC, they could, but it was much more - it was much harder to do when you were smoking a joint that was 1 or 2 percent THC compared to something that's 25 percent THC, much less smoking these extracts that are 90 percent or 95 percent THC, or ingesting edibles, which is, you know, an increasingly preferred form of use, which goes through the liver and becomes an even more psychoactive form of THC.

WALTERS: I think that's one important point because you hear edibles are more - well, they're more attractive. They're also - thinking of, you know, a gummy bear or juice or something where children can be, or young people, can be encouraged to use it. That is - that it's also not neutral in regard to THC.

BERENSON: I can tell you, you know, from talking to people who are experienced users who've had bad experiences, you know, bad psychedelic and psychotic experiences on edibles that they did not expect. But so talking about this time lag between use and permanent psychosis - you know, there's data from Finland that suggests, you know, if you're hospitalized for cannabis psychosis, there's almost a 50 percent chance in the next several years - I believe it's eight years - that you'll ultimately develop it. You'll get a diagnosis of schizophrenia. There's strong data showing that if you begin using as a - you know, as a teen, that you're - that you have an earlier onset of schizophrenia, which suggests that, you know, that it's accelerating the development of schizophrenia. And I think there's data - I want to say it's from Denmark - again showing - this showed a shorter period. I think it was a three- or four-year lag between that first hospitalization and a permanent diagnosis of schizophrenia. But you also have to realize that's not the first day of use, that's the first time that you come to the attention of the, you know, public health system.

So I mean, you put it all together, is it three, four, five, six years from use to break? I mean, it probably depends on your genetic vulnerability. It probably depends on how heavily you use. It probably depends on when you start using. And now it depends on the potency of these products. I can tell you, having heard from parents, now many parents since the book came out, there are clearly kids, young adults - teens and young adults - who begin using and, within a matter of months, are basically hopelessly addicted to this drug and continue to use even as their mental health rapidly unwinds. So I heard last week from a doctor in Texas whose son began to use at 15, within a few months, had left - had dropped out of the high school he was in and went to a private school, and less than four years later was diagnosed with a psychotic break, was admitted to a hospital - or I should say showed symptoms of psychosis, was admitted to a hospital, was discharged and shot himself in the head a few days later. So that's less than a four-year period.

You know, I've heard - I mean, it's - I think the more psychiatrically healthy you are at baseline - and this is just basically a guess, based on inference - the probably the longer it takes for cannabis to break you, if it's going to break you. And so, you know, I've also heard from people who are in their 30s who say, you know, I've used for a long time, and recently I've had symptoms. But I've also heard from people in their 30s who say, I never used this drug, and I started using, and within a matter of months, I started to have paranoia and, you know, quasi-psychotic episodes, and I didn't really put that together with my use, which seems astonishing to me. And I do think there's - I do think there are books to be written from the user perspective. I - you know, the equivalent of the lost weekend, the novel and the memoir that is about, here's how I slid into this, even though I knew it wasn't a good idea for me. Those books really have not been written for marijuana, at least as far as I can tell. So it's a several-year gap.

And - but what I do worry is that with the high-potency stuff and with the sudden advent of JUUL, you know, which has really taken off in the last three or four years, which is vaping nicotine, and many kids, many teens, who start by vaping nicotine wind up vaping THC very quickly. That some of those kids are going to break not in, you know, five years but in one or two years. And if that's correct, we might start to see a real epidemic of psychosis in the next couple of years. I'm not saying that's going to happen, but I will say this - one of the things the legalization community says, one of their big talking points is, there's been a huge increase in cannabis use in the West in the last 25 years, and you know, even dating back longer than that, and there hasn't been a population that will increase in psychosis. First of all, in the U.S., we don't know if that's true. There's actually some hints now that there are - you know, that psychiatric inpatients, hospitalizations, in people 18 to 25 have gone up a lot in the last few years. And we don't have any national data on the incidence of psychosis, either schizophrenia or more broad definitions of psychosis. But in Denmark and Finland, which are two countries where they actually have done a good job measuring this, there's been a real increase in psychosis - or in schizophrenia diagnoses between 1993 and 2013 in Finland, and 2000 to 2012 in Denmark, and both of those countries saw a big increase in cannabis use in the '90s, and they've seen the big increase in potency that everywhere has more recently. And so you can no longer say there is no evidence of a population that will increase, just like - and that does not prove - it does not prove that cannabis caused those increases. What it says is, if - one of the things that the legalizers say is no longer true. And another thing they say that is provably untrue right now is that cannabis legalization will lead to decreases in violent crime. That is provably untrue based on what's happening in Colorado, Alaska, Oregon and Washington, which are really the only four states where we have any, you know, data for more than a year. Crime, violent crime, murders and aggravated assault, have increased substantially in those four states since 2013, when legalization - when recreational legalization began in 2014, you know, January 1, 2014, in Colorado.

And you know, if you look at murders in Denver, murders in Denver almost doubled between 2013 and 2018. Murders in Seattle almost doubled. Aggravated assaults, which in some ways to me is a more important number because, you know, whether you live or die after a beating or a gunshot can depend on a lot of things. It can depend on how quickly you get to the hospital. These are relatively small numbers of homicides. Ag assaults are a big number, and those have gone up about 50 percent in those two cities, you know, and in Portland and in Spokane and in Anchorage. You know, there's - the people who said legalization is going to reduce violent crime, it's going to give police officers a chance to focus on violent criminals, it's going to end the black market - as Cory Booker said in 2017, when he introduced a bill to legalize marijuana at the federal level, those people need to stop saying that. It's not true. And if journalists had been doing their jobs and fact checking Cory Booker, they would have pointed out that it's not true. I don't understand why cannabis is not fact-checked.

WALTERS: Yeah, I wanted to ask you because I think one of the criticisms that you touched on, that the book has received, is the argument that a lot of the evidence is based on correlations and not cause and effect. This was, of course, an issue with regard to smoking and cancer and other kinds of things, where these phenomenon are probabilistic, or these phenomena have somewhat complicated causal links, some of which we understand, some of which we don't, but we see where they - can you say a little bit about how - for the person who hears that kind of criticism, and they say, oh, well, you know, you're saying the rooster crows and the sun comes up, so the rooster caused the sun to come up. Can you say a little bit about what's really going on here, and how this is really thought about to the person who hasn't, like, gone through the data the way you have.

BERENSON: Sure. So correlation does not prove causation. But you know, the rooster crows, and the sun comes up. But the Earth spins, and the sun comes up. OK, so looking at correlation is a good place to start. And when you're an epidemiologist or, you know, or a clinician scientist, there are various measures you use. Can you see a dose-response curve? Is there a plausible biological mechanism. In the case of cannabis, when you challenge and de-challenge people with pre-existing schizophrenia and others, when you - when those people stop using and begin using again, does their disease worsen? Is there a way to look at analogs to THC and see if those cause psychosis? Is there data that's reproducible from different countries, from different time periods? Can we look at confounding factor - family history of mental illness, other drug use? Can we look at pre-existing symptoms of psychosis? And all of those boxes have been checked for cannabis, OK?

There will never be a randomized controlled trial to see if cannabis causes psychosis. That would be completely unethical. It would not be allowed. First of all, it would be impossible because it would require many, many thousands of people for many years. But it would also be completely unethical. So if you were going to demand an RCT to prove this, then you're never going to get that. And you're always going to be able to say, OK, you know what? This hasn't been proven to a scientific certainty. Guess what? There's never been an RCT that shows that tobacco causes lung cancer because that would be equally unethical. But when everything points the same way, and you have - I would say the weaker - the weakest part actually, the part that's weaker is not the RCT, it's - because brain science is so primitive, despite all the work that we've done, or the many good scientists have done for many, many years, we don't really have a biological story to tell.

We know that, you know, tars and tobacco can cause problems in cells, DNA, and you know, and so ultimately you get cancerous changes. You get - you know, you get your changes that lead to tumors. But we don't know how schizophrenia develops, period, really. We don't know - there's no blood test for it. There's no brain scan for it. There's no way to send somebody - this is a disease, and psychosis, generally, and much less the sort of the less-severe forms of mental illness, like depression and anxiety, these are all basically self-reported. And so if you're going to say to me, you can't show me in the brain how this causes schizophrenia, I'm going to say, OK, you show me what schizophrenia is in the brain. You show me what the disease, the disorder, actually is. And guess what? We don't have that. So I would say the science is very strong.

WALTERS: Good. And what - in that regard, I want to also ask you - since we're - since you're seeing and you tell the story of some of the people who have suffered from schizophrenia and then breaks with reality and been involved in violence, do you think the medical community is sensitive enough to this and is diagnosing this? I recognize you started with your wife, who's an expert. But I also wonder whether there isn't some denial on the part of people who are frontline and treating people.

BERENSON: So the psychiatrists know. OK? I mean, it's funny because as I - the DPA, the Drug Policy Alliance, they got - they wrote this ridiculous letter, you know, claiming the book was racist and this and that. I challenge anyone who reads the book to figure out where it's racist. The DPA got these people to, you know, to sign this letter, but almost none of them were MDs. Almost none of them were doctors who treat patients. And only two of them, as far as I know, were psychiatrists, and both of those people had longstanding connections to the cannabis industry, OK? The shrinks don't want to deal with this. They have enough heat over ADD and being called, you know, pill pushers. And this is a difficult issue to deal with. They know. The ER docs know. They see it every day. But if you're an ER doc, your job is cleaning up the wreckage, OK? It is going into the hospital knowing that somebody's going to come in in a car accident or, you know, with a gunshot wound or floridly psychotic and just trying to fix them. This is not a person you have a long-term relationship with, although you might see the person over and over again these days (laughter). And so they - the people who see this the most closely don't want to deal - don't - either don't want to deal with it in case of the APA, or just it's not really in their purview.

The pediatricians have actually done a somewhat better job. And the AMA has, you know, mostly stayed away from it. So the clinicians haven't spoken out as I wish they would. I think that as this problem gets worse, ultimately they will start to speak out. And by the way, unfortunately, you know, if you look at the history of doctors, especially primary care doctors, prescribing psychoactive drugs in the 20th century and, you know, right up to the opioid epidemic, it's not a great history because these people - if you're a doctor, and your patients are demanding X or Y from you, it is sometimes easier just to write the script and get them out of your office. And if your patient is smoking cannabis and showing signs of disordered thinking or psychosis, if you're a primary care doc, and you're getting - you know, you have a 10-minute window, and then you've got somebody else coming in, you're going to try to get that person out of your office to a psychiatrist. This is not somebody you want hanging around. This is just a fact of medicine, and I don't blame clinicians for it. It's just a fact. But so it's the people who see floridly psychotic patients who really know, and they just have not spoken out yet.

WALTERS: The legalization effort, as you have discussed, had two stages. The first was to talk about marijuana as medicine and then to use the people who, you know, made claims that, I use this; I felt better. My family member used this. I felt better for a variety of maladies - people who spoke with power and some sincerity and then moved to large-scale or recreational legalization. Since a lot of people, even the audience, are going to hear and have heard the kind of testimony of people saying - and then plus you now have people who advocate for our veterans who are suffering PTSD, they need to be given marijuana. This is legitimate form of treatment. There's been efforts to get the VA to feel out this, be prescribed. Can you talk about how to understand that?

BERENSON: Sure. So there's a couple confusions here that the industry and the legalizers have pushed. First of all, there's a confusion between CBD and THC. CBD is non-psychoactive. CBD, you know, you can buy in most of the country, in grocery stores these days. And you know, it's marketed for a variety of things that it probably doesn't do very much for. It does - it actually does work as medicine, as, you know, a medically prescribed drug to treat childhood seizures, which is really great. And you know, there is a company - you know, there are several companies, but there is a company in Britain called GW Pharma that is actively looking for other ways to treat people with CBD and with other cannabinoids, other chemicals in the plant, and that's great. I mean, you know, I think that if there are chemicals in marijuana that are beneficial as pharmaceuticals, we should find those, and we should use them. And by the way, the idea that that research is not being actively and aggressively conducted in the United States is completely untrue, despite the Schedule 1 designation. You know, the University of California has a center for medical cannabis research. So there's CBD.

And by the way, you know, if you think CBD is going to treat your arthritis or your insomnia or give your dog, you know, a glossy coat, you know, basically have at it. It doesn't really matter. The stuff is, for most people, probably relatively benign. It's an expensive placebo. Then there's THC. THC is the thing, is the chemical that people use to get high, OK? When people smoke marijuana, they want to get THC into their lungs, into their blood, into their brain, because THC activates the CB1 receptor in your brain, and it gets you high. It has very little to do with CBD, even though they look almost the same chemically. CBD does not touch the CB1 receptor in your brain. And so all those stories about people taking CBD and, you know, miraculously getting their sight back, or whatever, have nothing to do with why most people use marijuana - most users. And the legalization community is totally aware of that. As for THC's medicinal properties, they are - you know, so they - THC has been shown to help with chemotherapy-associated nausea. You know, for people who don't have chemotherapy, that's obviously not an issue. There are also, by the way, other drugs that work with that.

But OK; it works for that. That's great. There's an idea that THC has really been shown to work to treat pain. Not really. THC, because it's an intoxicant, probably reduces your sensation of pain in the short run. For the most part, it's only been compared to placebo. You know, if I gave everybody here, you know, a shot of bourbon, you'd all probably feel a little less pain in the short run, too. It doesn't mean alcohol is a good pain reliever in the long run. And there's actually good data from a study in Australia that came out last year showing that people who use THC had more pain at the end of four years and used more opioids at the end of four years than people who didn't. So the idea that THC really should be approved for pain relief is - the FDA would never approve a drug for pain relief that has the weak clinical trial data that THC does for pain. And by the way, at this point, I think THC probably can't realistically be tested for most conditions because its psychiatric side effects are so obvious now that you'd have to exclude many people from any clinical trials. And certainly for long-run chronic conditions like pain, there'd be no ethical way to run clinical trials for that. So - but the cannabis community deliberately, to my mind, confuses CBD and THC, and they don't acknowledge that most people who got those medical marijuana authorizations in places like California and Colorado were recreational users before they ever started using.

You know, Rob Kampia, who runs - who used to run the Marijuana Policy Project, he was honest with me about it. He said, you know, 6 percent of people who use - who got those authorizations really had some legitimate medical purpose. Everybody else we were protecting from arrest. OK, to me, this is one of the great, brilliant, cynical moves in American public policy in the last 25 years. If we want to legalize this drug and say, this is a recreational intoxicant, it has psychiatric side effects, it's going to kill some people, it's going to destroy some people, but you know what? Alcohol does that too, tobacco does that too. You can go to a casino and see people who've lost their homes. We're adults. So be it. Then OK. But pretending that this is medicine is a great lie, and it has confused a lot of well-meaning people who don't use the drug, who don't know what it's used for. And that's why 95 percent of the country favors medical marijuana. Americans are fair-minded people. And the idea that, you know, if I'm dying of HIV or cancer, I should be allowed to use whatever I can because it might benefit me, that argument had great traction. The fact that it has nothing to do with the reality of the drug didn't bother the psychiatric community - or the legalization community, et al. And by the way, we're seeing a very similar move made with psychedelics right now, where, let's legalize this stuff for people it can benefit, for end-of-life use. You know, one of the - the modern medical marijuana movement started in 1996, prop 215 in California.

What people don't know is there was a second ballot initiative that year. It was in Arizona. But it didn't just cover marijuana. It covered all Schedule 1 drugs. It covered heroin, LSD - you could use anything with a physician's authorization. And that was - and it passed. It passed (laughter). And the Arizona legislature said no way. And after that, the legalizers got smart. They never made that mistake again. They always said marijuana is not like other Schedule 1 drugs. It's much safer. It's medicine. And that argument won. And you know, among the many terrible things that that has done is it's confused people who are most at risk, people who have psychiatric conditions, who might actually believe that this is good for them, people who are at high risk of addiction, who have been sold the myth that somehow cannabis is a cure for opioid addiction, when there are generations of data showing that the gateway theory is correct, showing that you are much more likely to be a user of heroin or cocaine if you've use cannabis first and showing that these drugs, on an individual basis - forget the statewide epidemiological data because it's weak, ineffective and meaningless - people who use first are much more likely to use opioids three years later. There's a very good paper in JAMA Psychiatry that's gotten no attention, whereas the Bachhuber paper that was published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 2014 still gets referenced, even though the data is 10 years old, and if you look at more recent data, it's - the finding's basically gone. So the - once again, this is journalists failing. This is journalists failing to tell people what they need to know. It is embarrassing to me as a former journalist that people have been so ideologically driven.

WALTERS: Yeah. I mean, as a last question of - some of the work that we do at Hudson involves employment, economic analysis, policy with regard to regulation, and some of my colleagues and some here have been talking to people in the business community, in the trade - involved - and asking them about how they see certain policy options, trade policy and others, and found that they'll get stopped by people in the business community saying, wait a minute. I'm having trouble finding a sober workforce. I'm having trouble finding people who can stay at work. And I'm having trouble paying the health care costs of them and their families because of substance abuse, across substances. I mentioned to you I saw a video from the cannabis advocacy organizations talking about, hey, get in on the ground floor of this business. It's going to go to a trillion dollars. It's going to be like buying, you know, Apple when they were in a garage. There's a lot of force moving this forward, and I guess I'd like to know what you see is going to happen in the next five to 10 years.

BERENSON: Well, I think it's quite likely that we'll get full national legalization. I think if a Democrat wins in 2020, that's extremely likely. Basically, all the candidates have come out in favor of it. You know, it's funny. This has been driven by the media, which is - well, it's been driven by the legalizers, who've driven the media, who've driven voters. And you know, if you're a representative and 65 percent of the country wants something, it's pretty - you know, even if you think it's a bad idea, eventually, you know, the will of the voters does typically win. And so this is going to take a long time to turn around, I think. And it's going to take a long time for the truth to come out, is what I should say. And you know, in a year or two, I don't know what my life is going to be like. I feel like I've been forced into a position where I've had to defend my book. I know my book is true. I know that what people are saying about it is not true. And so I'm going to keep defending it. But you know, I'd like to go back to writing novels.

(LAUGHTER)

BERENSON: Not that I don't enjoy, you know...

WALTERS: (Laughter). Like I said, he's getting a bit of the drug czar experience of vilifying you and attacking you. And you know, it's...

BERENSON: It's really amazing how personally - but so - but whether or not I do that, there are parents out there, a lot of parents already, who have lost their children to this. And if you think that losing a child to opioids and getting the call that your son OD'd is the worst thing that can happen to you, you are wrong. The worst thing that can happen you as a parent is knowing that your son is on the streets somewhere, schizophrenic, your college graduate, bright-future son, who started smoking and who got psychotic and has been psychotic and has been hospitalized over and over again - that call that you're waiting for in that case is not, he died of an overdose - it's, he killed himself, or he killed himself, and he killed someone else, too. And those parents, they are not going to forget, and they are going to fight this industry.

And it's really interesting to me how quickly things turned in the '70s. Once, it was the same situation where - legalization - I mean, there was not the same level of public support, but there was rising public support. There was a Democrat in the White House in the late '70s. You know, there was there was this feeling that, let's do it, you know, the counterculture has won, marijuana is not so bad, which was certainly more true then. You know, the THC levels were much, much lower. Nonetheless, once enough parents saw what had happened to their kids, and once it became clear that cannabis use, you know, lead to cocaine use for a lot of people - it's so amazing to me that people - that the legalization community has managed to snow people on the fact that cannabis use is so high in this country and opioid - I mean, we have an opioid crisis, we and Canada - two countries with the most cannabis use, the most opioid use. But - the most - you know, the biggest number of opioid overdose deaths, I should say. But once that happened, once parents saw firsthand, the support for legalization basically blew up overnight. And marijuana use went down. From 1979 to 1991, it went down by half. And to some extent, that set the stage for what's happened now because, you know, there was - so many people had - weren't using it then. It was, you know, a relative niche drug. And so when Prop 215 hit, the legalization community had a large group of people who had no idea. But the - you know, the collapse in public support was very fast.

And you know, legalizers have been savvier this time, and they've sort of tried to avoid at least explicitly marketing to teens. And so there aren't as many teens using relative to the number of young adults using as there were in the '70s. That's the one good thing that's happened in the last 15 or 20 years. But because of JUUL, because of the vaping of nicotine, which many people then - or many kids, many teens, start using, pretty rapidly, THC, all the sudden we're exposing a lot of teenage brains to high-potency THC. And there's going to be a lot of parents who don't like what they see. And I'm not saying that - I don't think that - I think legalization right now has a tremendous amount of momentum, and I do think that if a Democrat wins in 2020, it's probably going to happen. It will be a tragic public health mistake if that happens. If - you know, if Donald Trump is reelected or, you know, Howard Schultz, whatever - if a Democrat does not win in 2020, it is possible, I think, that the health consequences will be so obvious within a matter of years that there will be a collapse in public support for legalization, and the tide will roll out again, as it did in the late '70s. But if - you know, if you gave me a dollar and you said, you have to bet on legalization or not, I would bet on legalization in post-2020.

WALTERS: But I - I don't want to put words in your mouth - I take it from your book that even if legalization happens, that the consequences given what - the momentum, the potency, the growing evidence of violence and mental illness, is such that even if legalization happens, it's just not sustainable.

BERENSON: Well, we have, you know, 10 million people die in the U.S. from cigarette smoking. You know, cigarettes are still legal. You know, alcohol kills a lot of people. Alcohol is legal. The difference - I would say the one difference is that psychiatric hospitalizations are so expensive that if, you know, if you have to open a ton of new hospitals - but probably we wouldn't even do that. We'll just dope people up on olanzapine and clozapine, and you know, and we'll just have a whole bunch of zombies walking around.

WALTERS: You fear that is sustainable?

BERENSON: Unfortunately. Here's the one other thing that, you know - the violence associated with this kind of psychosis is deeply disturbing to people, as it should be. And if that continues and rises...

WALTERS: You make a comment here that some of that - none of these are horrendous, but a disproportionate amount of it is focused on children.

BERENSON: Children, vulnerable adults, you know, strangers. It is not the sort of classic bar fight where, you know - that turns into a gunfight where one guy - either person could be the victim, and either person could be the perpetrator. Psychotic violence is not like that. I mean, one of the problems with it is that it's so awful that oftentimes the elite media just doesn't even want to - you know, they just kind of say, we're not going to talk about this. But that could turn things, too. But we - twenty years, 20 years of myths, 20 years of bad journalism doesn't get undone overnight. There's going to have to be unfortunately some negative consequences that people can see with their own eyes, I think.

WALTERS: Well, we'd like to open up to some questions. Let me preface that by saying a question is a relatively short sentence or two with a question mark at the end of it.

(LAUGHTER)

WALTERS: If you want to make a statement, that's fine. The internet exists for that. Let me ask that we take some questions from the audience, and I'll open it up to anybody. Sir? Could you wait for the microphone, since we have people listening? Thank you.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Thank you, Mr. Berenson, for an interesting presentation. And my question will be about the legalization process globally because it seems that it effects the legalization process in the United States also effects - have some consequences on the global - globally. In developing countries where the law enforcement is weak, for example, it might become more problematic. But we have examples. For example, in Armenia right now, there is a public discussion, public debate, about whether it needs or not to decriminalize and legalize marijuana. Your comments on that.

BERENSON: I mean, it's certainly true that legalization has been led by a community in the U.S., which, you know, again, has essentially lied about the state of legalization elsewhere. You know, based on the data that I've seen about European drug arrests, you're actually more likely to be arrested - and this is even previous to the, you know, decriminalization in Cal - or the full legalization in California and other states - you're actually more likely to be arrested for possession throughout Europe, relative to use rates, as in the U.S.

I mean, I think - look, if I were in another country, if I were a policymaker in another country, and they may - you know, they may feel some of the same pressure from voters, but if I were a policymaker in another country, I'd say, you know what? Let's see what happens in Canada and Colorado and California, and if it looks great, you know, if they - if those countries - if those places sail into the sunset of higher tax revenue and, you know, no increase in violence, and everybody gets to have a joint at the end of day, and we're all, you know, singing "Kumbayah," let's go for it. But you know, that's not what's going to happen. And I think, you know, to the extent that this process gets delayed, it's bad for legalization because the harms are - become so obvious fairly quickly. So you know, I just think - you know, I know that in Spain they're considering moving forward. I know in Italy they're considering. I just think, you know, again, if you're a policymaker in another country, what is the rush on this? You can watch what's happening in Canada and the U.S.

WALTERS: Other questions? Yes, ma'am? Just a second. Wait for the microphone.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You mentioned physicians several times, and there is an American Society of Addiction Medicine that focuses on addiction issues. There's also many efforts nationally to train physicians to identify addiction issues and then refer into treatment. But my question to you is, given what you say is a lack of ownership or training or responsibility, what do you think we should, as a country, do to train our physicians better?

BERENSON: Well, I'm not going to pretend to be an expert on medical education. I really was talking about it in the context of, as a physician, you know, in the real world, seeing your patients day to day. It was not a psychiatrist who's not trained to deal with people who are psychotic. And you know, psychiatrists receive training in what to do about violent patients. They need to. You know, that that's a difficult spot in the real world. And you know, obviously it would be nice if physicians - it would be nice if patients were honest with their physicians about their use, and it would be nice if physicians could have, you know, long conversations about this. I think in the real world that's a lot to ask. What I would hope is that at the top level, at the AMA, you know, at the sort of national congress level, that the leaders of these, you know, societies would take a public position and get people - you know, get the public aware of the seriousness of the issue.

WALTERS: I think there was two parts of your question, if I can just - when I was in the White House Drug Policy Office, we sponsored with some of these medical groups in effort to increase the training of physicians and, frankly, frontline ER personnel to do screening and do brief interventions, referrals to treatment and so forth, to begin to kind of do that pervasively in the health system because that was - we knew that people that had substance abuse problems were more likely to come into that system and could be better reached - not every time, but the more you try, the more you get.

The other part of this, of course, is what I was just referring to which is, you know, a kind of honest statement about the fraud that's going on here, by the people who have the medical credibility and the organizations that have that credibility, about the danger, about what needs to be looked at, about some of the systems that we've had and let go dormant to report on what's happening in emergency rooms with regard to substance abuse episodes, what's happening in regard to the nation. We have a vast system that involves a lot of government payment for services as well. We could begin to track this in much more real time and to see what's happening in more aggregate form in places like Colorado or California or other parts of the country. We're not using the data in that way. There isn't the kind of urgency, and some of that urgency would come if some of these professional organizations would say, we ought to be investing in learning because there's a danger we know and we want the country to be aware of. There's not chapters of Profiles in Courage being written here. Other questions? Why don't we start back there and come - all right, we'll start here. Hi.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hi. You talked about all the people who attacked you or the different organizations, but are there any that you feel like, now that you've put this all out there contained in one space, are taking a second look or that have been more receptive. Or is that really not happening? Is it just this tug of war between you and the legalization community?

BERENSON: If there - if the DPA is having conversations about ways to more honestly discuss these risks, they haven't told me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: John referred to more and more workplaces that are having trouble finding people who are not on one form of addiction, one form of drug or another. Is there any data yet to - on things like workplace accidents or maybe more generally in things like traffic accidents?

BERENSON: There's some data coming out of Colorado and Washington. I mean, in general, traffic accidents where THC is found in the bloodstream of the driver have gone up. I don't know about workplace accidents. I will say that, you know, a couple of times from people, you know, on the legalization side or, you know, scientists who are - sort of favor legalization, they've said to me, well, you know, this book does a disservice because you're talking about this risk of psychosis, this risk of severe violence, and that's not the real problem with cannabis. The real problem with cannabis is that a lot of people get addicted to it, and it messes up their lives, you know, and they just don't really work. They - you know, they just kind of float through life. They're not as successful as they could be. And I say to them, is that a reason to legalize? I'm confused about what you're saying here. I mean, it does seem clear that there - you know, whether you believe the IQ data from Dunedin or not, that there are, you know, strong measures of societal disadvantage that cannabis use seems to worsen.

You know, I didn't focus on that in the book because I thought this risk was so important and not very well understood. But I do think that, you know, a country where several million people are daily users, where we've essentially created a population - so there's 12 million daily users of alcohol every day. Now, not all those people have a problem, but certainly people probably who are using alcohol all day, every day have a problem with alcohol. And there are now 8 million-plus daily users of cannabis. That's a tripling in the last 15 years. And a lot of those people do use all day, every day. I mean, that's a wake and bake. That's, you know - it's called that for a reason. And so - and those people use - a lot of them use a lot of cannabis. Those people are not - look, that's a personal decision, OK? Really, it is. And I'm not a, you know - I'm not going to, you know - I drink, I play cards. You know, that's your decision. But you are probably not achieving all you could if you are going through life that way. Now, maybe there are some exceptions. But there's quite a bit of evidence that people who use at that level, you know, do have problems.

WALTERS: Any other questions? Yes, ma'am?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I wonder - when you're talking about politics, and we're watching somebody like Kamala Harris making marijuana look really cool and wonderful, are you seeing anything on the left - either academia, politics, anybody saying - other than her father (laughter) - this is not cool?

BERENSON: No, no. And you know, people like to call me Nancy Reagan. They like to call me Harry Anslinger Junior. It's fine. You know, I was - I almost got my head cut off...

WALTERS: There are worse things than...

BERENSON: That's right. That's right.

(LAUGHTER)

BERENSON: You know, I've - you know, when you're an investigative reporter, you get used to people saying mean things about you. Although, this is a larger group of people saying mean things about me. But no, no, the left loves cannabis. I mean, my joke about this is that when I want to get high, or when I want to get psychotic, I don't smoke pot; I watch "High Maintenance," which is a show on HBO with your friendly, neighborhood drug dealer riding around Williamsburg, delivering to - no joke - a nine-month pregnant woman and, you know, a bunch of teenage girls. And I mean, would that be OK if he were delivering heroin? Or you know, even if he were delivering alcohol, would we be cool with the portrayal of him as a hero? But cannabis is its own island. It's bizarre. It is - you know, it's like - it's half-garlic and half-St. John's, with a tiny bit - of St. John's wort, with a tiny bit of alcohol in there. You know, it cures what ails you. It makes you a better mother. It's just bizarre. This is a recreational intoxicant with psychiatric side effects, and why we pretend it is anything else is just beyond me.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Hi. As a journalist, I want to say that the - I think it has also a lot to do with the fact the media is shrinking so much, and there's more news than ever to cover. But I wondered if you could just touch on some of the other things, like fetal - relationships to perhaps some sort of fetal syndrome, like what's happening to kids and also the link to depression and other mental health disorders. And I'd love to know if you actually, Mr. Walters, do you - where do you stand on this? Like, are you opposed to further legalization?

WALTERS: Yeah. I mean, we - our center is designed - was designed to try to help put out some of the information that's available in some of the research that's going on, some of the surveys that go on, because they're not covered. I mean, I think marijuana - it is correct marijuana is the biggest distorted spot of both reporting and in our consciousness, a kind of denial about what's been happening because, as he pointed out, some of the evidence here - and then he found it - goes back to medical studies that are from the 19th century. So this has not been a mystery in terms of science and reporting, and it goes right up through. I mean, there are - there's Senate testimony, or House testimony, that was done shortly after World War II about substance abuse. I mean, we've had a lot of information, and it's all been going one way. And in fact, the most recent research is even more troubling because it shows the effects of both higher potency, it shows the effects of what we're now able to measure with regard to psychological as well as other cognitive problems.

The problem is not that the evidence isn't there, and that's what's so, I think, masterfully marshalled in Alex's book. But that people don't want to hear it. They don't want to see what's around them. And that's why I also think one of the most shocking parts of his book is the part on violence, where he talks about what you're - what we actually see from notorious, nationally publicized events of violence that involve heavy cannabis use and people - sometimes it's not reported, sometimes it's reported trivially - and people don't want to see it. If you bring this up, if you bring up the kind of mass, violent, shocking crimes have a link to cannabis use, that's considered to be an illegitimate comment. That couldn't possibly be true because we all know that this just makes you like Cheech and Chong. It doesn't make you like a bad, violent, dangerous person. And yet, over and over again, you see these events, and they're just dismissed. So, I mean, that is a problem. I think that's both a journalistic problem. But also, look, journalists are also - they're not politicians, but they are selling to an audience.

And if you say things that people say, that can't possibly be true, they don't listen to you. So you know, there is a real problem here, and it's a service for Alex, people like him. And what we tried to do in our own small way is to try to get some of this information out because, I mean, frankly, there was a reluctance to do that in the Obama administration. They had a policy position, and they did not want to highlight the - some of the data that was happening. OK. That was political - I think it's wrong. I think it's not keeping with the truth. But OK. But even now there's a lack of willingness to address this. And you see the pressures that are going on on Capitol Hill with regard to both parties. Look, we have former speaker John Boehner who is the spokesperson now for a part of the cannabis industry. He was involved in this video I saw about, it's going to be a trillion-dollar industry. Get on the ground floor.

BERENSON: (Laughter).

WALTERS: You're stupid if you don't do this. Everybody's going to be using it all the time.

BERENSON: There may be a trillion dollars of liability associated with the industry.

WALTERS: Well, I'm waiting to release the sharks. That'll be a better outcome here, but we'll see. And I don't know - you asked Alex about the - some of the data about young people and infants.

BERENSON: I mean, I think there's some interesting evidence. I don't think anything's been proven. It's very hard with, you know, with pregnancy, first, you know, how you're going to accurately measure risks or accurately measure use. And you know, oftentimes these conditions are relatively rare. You know, severe, you know, birth defects are relatively rare. So it's hard to pick up. So I don't think anything has been proven. I mean, I shouldn't say that because the NAM, I believe, may have mentioned a couple of places where there's strong evidence, but off the top of my head, I can't think about what those are. I can't recall. I'm sorry about that. As for depression, yes, there's definitely now increasing evidence that cannabis use as a teenager is linked to depression. JAMA Psychiatry had a paper, I think it was either last week or the week before, on that issue. I mean, to me, that's not surprising. Psychosis is the most severe mental illness really. If cannabis can cause psychosis, why would it not be able to, you know, produce other forms of mental illness?

You know, again, that's sort of a - I don't want to sound overly flip, and you know, I'm not a brain scientist, but that's my gut reaction to that. I think the idea that you would use this to treat your depression and anxiety, or that manufacturers and distributors and retailers of this would promote it for that reason - you know, as I saw last year when I was in San Francisco, the big billboard that said, you know, hello marijuana, goodbye anxiety. That is bizarre, OK? We don't promote alcohol that way. You know, and in the short run, getting drunk may be a solution to your depression. But in the long run, it is not. It will make it worse, most of the time. You know, and ditto your anxiety, ditto other psychiatric conditions. We don't pretend alcohol is anything but an intoxicant, but we pretend marijuana is medicine, and we're told it's medicine. And that - you know, that needs to end. And you know, the people who've - I think the legalization community doesn't realize on some level that it has seized power, that it is in power now, that basically it has won or almost won, and that it needs now to stop spreading myths and start telling the truth and start encouraging responsible use of this drug, that is something more than, start low and go slow, which doesn't really mean much of anything. You know, the - but you can't - again, I go all the way back to this, you can't expect people who are selling this product, or who have an interest in wider use, and the legalization community definitely has an interest in wider use because the more widely the drug is used, the more accepted it will be. You can't expect those people to be honest, and that's why journalists need to do their own work. And guess what? There is a mountain of evidence.

WALTERS: Related to that, it occurs to me to ask you, though, I mean, some of this, you could say, is kind of public perception, and that's difficult, and there are legacies. But there are institutions that are designed and have the duty to make sure that when people make claims about health or quality of products or safety, that their job is to make sure that the public is protected. They're derelict.

BERENSON: They are derelict. The FDA hasn't wanted to touch this. The CDC has said - because, you know, I was talking to a Florida legislator last week, and he's - you know, he does not favor legalization at all, but he said, you know, even when we pick up this issue, we don't want to touch it because we get hundreds of phone calls. We get - you know, the people who are in favor of legalization, they believe this stuff is magic, and they do not want you to take away their magic. Or even, you know, forget take it away, even say that it might not be magic, even say that maybe you shouldn't be using it all day, every day; it's not a good idea. The anger and the vitriol - so people say, you know what? We got - we have opioids to worry about. We have - you know, we have the fact that, you know, 6-year-olds are spending all their lives on a cell - on a mobile phone to worry about. We'll worry about this one later.

WALTERS: But the marketing to things like - and there have been marketing to pregnant women - is obscene.

BERENSON: It's obscene, yes.

WALTERS: Most substances, even that are considered - proven safe for non-pregnant individuals are - have warning for, if you're pregnant, to be careful because of the danger of interaction. And to allow that to go on and to not shut that down, it seems to me is just inexcusable. You could say, I can't take on the big thing, but to not take on anything, even the small things, is outrageous. Yes, sir?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Just curious with Canada, the process they went through, because you're, you know - I'm thinking with the FDA and what they have, and maybe shed a little bit of light on - in other - how they went through it and made those decisions, and what type of research they had. And then my other comment would just be the best way to shut it down would be through lawsuits. I've seen plenty of drugs, you know, get taken off the market after they...

BERENSON: I think that - I think the liability issue is a real and serious one for people in the industry. And I've talked to some lawyers who agree, and we'll see. You know, as for Canada, I don't know that much about the precedent. It's funny. My wife is Canadian, and so we were up in St. John's, in Newfound - I've been practicing saying Newfoundland for years, and that's the wrong way to say it.

It's Newfoundland. I don't know why - see, this is again - should have listened more carefully to my wife. But so, you know - so her relatives are all nice Canadians, and they had the nice Canadian view of this, which is, everybody uses it anyway. And this way it'll be regulated, and we can get some taxes. And it's no worse than alcohol. Alcohol's probably worse, you know, and so be it. I mean, that's - and I do think that that is basically the attitude that most people who haven't thought about this issue, haven't - you know, who aren't aware of what the potency looks like, I think that's sort of what happened. You know, and so the Canadian government said, hey, let's do it.

I mean, basically, you know, this is going to happen. We want to try this. We think it's a good idea. And you know, Justin Trudeau campaigned on that, and he won, and it happened. You know, even in the - by the way, the murder rate in Canada in the last four years is up 30 percent, which is something that even a lot of Canadians don't really know. Now, that's pre-legalization, but use has been rising, you know, since the government signalized that legalization was going to happen. And again, opioid overdose deaths are a giant problem in Canada, with the worst crisis in BC, which has the highest rates of cannabis use. So the Canadians just - I mean, they just did it basically. Really, that is my impression of it. And they're going to see what happens. And you know, they do have some more warnings than we do, all right? You know, they at least - you know, since they did it nationally, there are some additional warnings. And they've tried to control edibles, which is interesting because, you know, just in talking to people we know up there, there's a lot of people who use edibles, and they're just going to continue to buy from their black-market suppliers. This is something that happens, and this has clearly happened in Canada - or in Colorado, in California and the other legalized states. Because you can grow your own, because there are taxes on the regulated product, there is a large supply of really cheap black-market cannabis in those states. And you know, and seemingly in Canada there's some of the same issues. Again, I'm not an expert on the market up there. And so you get the worst of all worlds. You get a legalized market where companies are promoting the product and marketing and making it more available, and then you get a black market that is going to provide cheap cannabis to, you know, to people under 21 in the U.S., 18 and under in Canada, who can't buy legally, who, you know, account for a fair amount of consumption, and there's violence associated with that. So you get the drug promoted without warnings, and you get Spike Jonze making videos for MedMen about how wonderful this is. And then you get a black market, too. It is really genius, what we have done.

WALTERS: Question?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Thank you for your book. It's terrific. How are you? I'm worried with the notion of when do we hit rock bottom? When does the parents movement recapitulate what we saw earlier? I'm not sure - I think we are underestimating the capacity of this industry to insulate itself, immunize itself, buy itself political power. We're seeing the donations and the pressures at the state level, now at the federal level, when you are engaged at the level of the U.S. Congress with banking regulations, which currently do not enable an illicit business at the federal level to pay their federal taxes, to open up the banking and investment structure, the whole financial apparatus, to what effectively is - the black market threat is not just people growing stuff on their windowsill and selling it below the registered dispensaries. There's transnational criminal organizations in Colorado with a footprint globally, who are well-armed, lethal and muscling their way in, who are sustaining, smuggling out of the illicit market and are insulating themselves with millions of dollars, that are now seeking entry into the U.S. financial banking structure and a rescheduling of the drug itself, which will then enable multiple laundered proceeds. It's much more threatening, I think, than we recognize, how you turn this back.

BERENSON: All right. So I don't deal with any of that in the book, right? To me, the book is about health and science. And to some extent, it's about if you're a parent, and your 17-year-old suddenly seems totally different, and you've noted, and all of the sudden, they tell you, yeah, I've been - you know, I've been smoking - I've been vaping THC the last six months. I love it. It's great for me. And it's like, well, how come you can't get out of bed anymore? The book maybe will give you the resources to deal with that. You know, I think what you're saying is true. But you know, you can argue that that's an argument in favor of full national legalization, right? That that's about the harms of prohibition, and you know, and sort of this crazy quilt of prohibition in some states and legalization in others, and people generating cash that they can't get into the banking system. I think - I honestly - again, I don't - so I certainly don't favor a legalization, but it would be better to have a conversation about that than where we are right now, which is nowhere, which - and we're not talking - we're pretending that this is medicine, and we're pretending that this is a solution to the opioid crisis, rather than that this is what it is. So but I'm not saying that, you know, there aren't - I mean, clearly, in California, there are cartels growing. In Colorado, there are cartels growing. But you know, it's just not - to me, that's more of a law enforcement issue and a political question, as opposed to a health and science question.

WALTERS: But there's also the part of this you've touched on earlier, which is that this topic, unlike other topics, doesn't have any consistency or rigor to the way we look at it because - I don't know whether you saw it, but ironically, there was a - there were a group of the retailers in California who came out strongly saying, there's too much black market. We need enforcement.

(LAUGHTER)

WALTERS: This is, like, completely unselfconscious to say there wasn't going to be a black market once there was legalization.

BERENSON: Right, right.

WALTERS: So you know, and nobody even says - nobody even kind of throws the bullshit flag here and says, you know, that's not true. So you know, what do you see as a kind of outcome when you can't have a discussion on this?

BERENSON: What you have is you have, you know, every Democratic candidate supporting legalization and full national legalization likely. I think we should take one more.

WALTERS: Yeah.

BERENSON: Because this man's had his hand up for a while.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What did you learn about our endocannabinoid system being the master regulatory of our body?

BERENSON: I would disagree with the premise of that question. I guess one more since this...

WALTERS: This gentleman?

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Since the train toward legalization seems to be going forward pretty quickly, would you favor some kind of restrictions on the strains or the potency or the TH levels - THC levels of...

BERENSON: No because you just wind up with the black market then. You just - again, it's the worst of all worlds. Let people see for themselves what an unregulated - or you know, a market that - where there's no discussion about prohibition caused this or law enforcement's responsible for this. Let them see for themselves what exposing lots of young minds to THC does, and you know, at the least, we'll wind up with some real warnings. Thank you, all.

WALTERS: Yeah, thank you. Thank you, Alex.