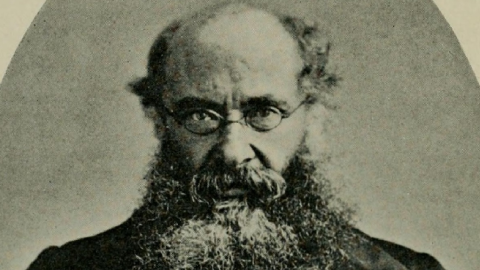

The bicentennial of the birth of the great Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope takes place this year, and there is no better way to celebrate than with the release of a nearly new Trollope novel. “The Duke’s Children” is being published for the first time in the form that the author intended. At 290,000 words—702 pages in the new Folio Society edition—the restored novel is 22% longer than the abridged version that was first serialized in 1879-80 and was the only known text until now.

For Trollope fans, the reconstruction of the original text of “The Duke’s Children” is the literary equivalent of being able to view Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” as it originally appeared. In the restored version, Trollope’s characters and themes come into sharper focus. Passages of beautiful prose are revealed for the first time. “It is an immensely better book,” said editor Steven Amarnick in an interview. Mr. Amarnick, who is a professor at Kingsborough Community College in New York City, reconstructed the original text over the course of 10 years with the assistance of Robert F. Wiseman and Susan Lowell Humphreys. Trollope’s handwritten manuscript of “The Duke’s Children,” showing the strikeouts he made as he was cutting the text, resides at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

“The Duke’s Children” is the final volume of Trollope’s Palliser series of six political novels. In the Pallisers—as in his earlier Barchester series of cathedral-town novels—Trollope wove an intricate tapestry of dozens of characters, interlocking story lines and grand themes. Writing in a pre-Freudian age, he offered psychological insights into the human heart that are as relevant today as they were when they were written. Virginia Woolf said readers believe in the reality of Trollope’s characters “as we do in the reality of our weekly bills.”

Michael G. Williamson, chairman of the London-based Trollope Society—who wrote the notes for the new edition of the book—concurs. “Much of Trollope’s reputation as a writer rests on his ability to create strong and believable characters,” he said in an email. Trollope’s drastic abridgment of “The Duke’s Children” “meant that, although most of the plot was retained and the book has been rightly admired in his shortened form, much of the in-depth characterization has been lost.” In cutting “The Duke’s Children,” Trollope did not eliminate any of the book’s 80 chapters. Instead, he deleted numerous passages and individual words. In doing so, he excised thousands of details about his characters.

The richer characterizations found in the restored version include that of the eponymous hero, the duke of Omnium, who is a former prime minister also known as Plantagenet Palliser. The duke is an aloof, enigmatic figure who plays key roles in the preceding Palliser novels. But it is only in “The Duke’s Children” that his inner life is explored in depth. That is part of the book’s appeal—to see a familiar character, a man readers thought they knew—emerge as a more fully formed person.

As the book opens, the duke’s wife—the vivacious Lady Glencora—has died, and the duke is left to deal with his three nearly grown children, their unsuitable suitors and their youthful peccadilloes. The duke, who has always been better at political maneuvering than at managing personal relationships, is at sea. The duke’s three children—Lord Silverbridge, Lord Gerald and Lady Mary—seem beyond his understanding or control. Trollope’s subject is the joys and sorrows of fatherhood.

“The Duke’s Children” is also about grief, about which Trollope’s descriptions may be unsurpassed in English literature. The book’s moving opening line is the same in both versions: “No one, probably, ever felt himself to be more alone in the world than our old friend, the Duke of Omnium, when the Duchess died.”

The restored version explores the duke’s grief in greater depth than in the abridged version. There is a poignant passage in which Trollope describes the duke’s guilt at having taken his wife for granted: “In those former days many a long evening he had passed all alone in his library, satisfied with blue-books, newspapers, and speculations on political economy, and had never crossed the threshold of his wife’s drawing-room; but now, when there was no longer a threshold that he could cross, he felt himself to be deserted.”

Silverbridge, the duke’s elder son and heir, emerges as a far more likable and sympathetic character in the restored version. “He comes alive,” said Mr. Amarnick, in a way he doesn’t in the cut version. Silverbridge starts out as a boy but becomes a man by the end of the book “and you see the steps along the way” to his maturity. It’s the “accumulation of subtle details that makes the difference.” Trollope is sometimes criticized for not devoting enough attention to his male characters, who often pale against the vibrant women who walk through his pages. In the extended version of “The Duke’s Children,” Trollope’s young men are as complex and credible as his women.

Both versions end happily, with the duke finally agreeing to accept Silverbridge’s and Mary’s choices of whom to marry. In the abridged text, the book’s final lines have to do with the duke’s grudging acceptance of Mary’s new husband. The concluding words of the restored version, however, set a different tone. Gerald, the younger son, gets the last word: “‘It will be my turn next,’ said Gerald, as he was smoking with his brother that evening. ‘After what you and Mary have done, I think he must let me have my own way whatever it is.’”

This ending raises the intriguing possibility that Trollope didn’t intend to end the Palliser series with “The Duke’s Children.” Did he have another Palliser book in mind? Did he plan to carry on with the story of Silverbridge, Gerald and Mary? We’ll never know. The author died two years after “The Duke’s Children” was published.

During his lifetime, Trollope was a prolific and popular writer, the author of 47 novels. His literary reputation, however, never soared quite to the heights of that of Charles Dickens, George Eliot and the Brontë sisters. His ranking has been on the rise in recent years, though, and the publication of “The Duke’s Children” in its original text should help keep that momentum going.

In the 1970s, the BBC’s lavish miniseries of “The Pallisers” built popular interest in Trollope. So, too, did the formation, in 1987, of the Trollope Society, which published the first complete edition of his work. Several biographies, out in the 1990s, enhanced the author’s academic standing.

“The Duke’s Children” is being published by the Folio Society in association with the Trollope Society. It deserves to be the new standard text of the novel. The expanded version is superior to the previously published one—richer, more expansive, subtler, wiser. In other words, to use a term of high literary praise, it is more Trollopian.