The power of narratives is as strong in the teaching of monetary economics as in any other area of learning. Yet the stories teachers use to demonstrate difficult hypotheses often derive from folklore rather than fact. In current economic discourse, neo-Keynesian economists shamelessly use mythical stories of what went wrong during the Great Depression in the US and during the ‘lost decade' in Japan to justify their favoured remedies. In this article, we take aim at their narrative on Japan and seek to replace it with another that better fits the facts, and yields quite different lessons for policy.

The Japan story as told by the neo-Keynesians describes a lost decade, the 1990s, with an extension into this century, portrayed as a debilitating period of falling prices and output. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is charged with failing to foresee and combat this effectively. By the time the BoJ seriously eased policy, it was too late. Japan had fallen into the ‘zero rate trap'.

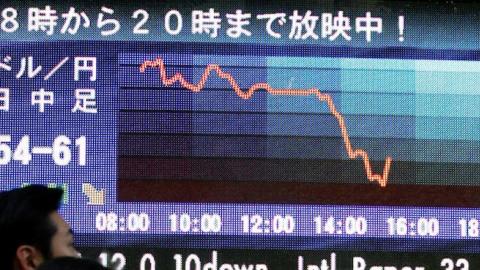

This narrative is factually incorrect. First, look at prices: the CPI in Japan in 2007 was at virtually the same level as in 1993, and up a few percentage points from the 1989 business cycle peak. Prices did fall through 2008–12, but this deflation was not ‘made in Japan'; it is explained by global factors, notably the global financial panic, the Great Recession and after 2008 quantitative easing (QE) in the US, which prompted a fall in the dollar and a relentless climb of the yen from 2007 to 2012 (from about 115 yen to the dollar to about 80 yen).

Taking the whole period from the early 1990s to 2012, Japan enjoyed reasonable price stability. Yes, the myth-makers can point to an alternative index, such as the GDP deflator, which records a mild cumulative price fall, but this reflects substantial ‘hedonic price adjustment' to take account of the changing quality of basket products, and would not fit the normal description of monetary deflation.

As for output, here too the lost decade is more apparent than real. In fact, recent work at the Bank for International Settlements shows that Japan significantly outperformed the US during the first decade of the twenty-first century, when proper adjustment is made for demographic influences. In particular, real GDP per working age population grew cumulatively by 20% in Japan from 2000–12, compared with 11% in the US. For the period 2000–07, the comparative statistics were 15% and 8%, respectively.

True, there was one lost half decade, 1992–97, when output lagged. But this was caused not by deflation, but by the collapse of the bubble economy that preceded it. Towards the end of Paul Volcker's time as chairman of the Federal Reserve, the Fed pursued a loose monetary policy to combat a perceived recession, which also had the purpose of depreciating the dollar in accordance with the spirit of the Plaza Accord of September 1985. As this drove the yen up to the sky, the Japanese authorities also felt compelled to ease their monetary policy to stimulate demand and curb the rise of the yen.

The extent of the disequilibrium and bad investments being made at the time was not evident to most politicians or academics (though the Bank of Japan (BoJ) was concerned). Once the credit-fuelled bubble burst, however, and the Japanese stock market plunged from its bubble highs (in early 1990), the gross misallocation of resources that had taken place became clear.

Given so much surplus capacity, and the burden of bad loans on banks, the scope for profitable investment was severely curtailed in many established areas of the economy. At the same time, consumer spending was weak as private savings rose.

What was needed was a fall in wages and prices, which would have bolstered profit margins while setting up expectations of a subsequent rebound. That would have been the natural route to a strong recovery, which would also have featured a key role for entrepreneurship. Businesses and households would have brought forward spending to take advantage of temporarily depressed prices.

In 2001–02, the BoJ launched its QE monetary policy, a first experiment of its form in modern times. The policy included a new element of ‘forward guidance', and the revised procedures for money market operations would continue in place until the "core CPI registered stably at zero per cent or an increase year-on-year". The intention was to remove the public's perception that the central bank had a deflationary bias.

The monetary experiment was expected to be fairly short-lived and had a clear exit strategy. BoJ policy-makers were constantly on the look-out for signs of asset price inflation in case there should be a return to the bubble of the late 1980s. They failed fully to understand that in this cycle, the asset price inflation disease took the form of a booming carry trade in yen – an outflow of short-term capital. Throughout the world, investors, including the Japanese, borrowed yen at ultra-low interest rates and sold it to buy foreign, higher-yielding assets.

From carry trade bust to hard yen

The financial crash of 2008 strengthened the yen. As the high-risk sovereign debt market bubble and related bank debt bubble started to burst in Europe, the rush for the exit from the yen carry trade – buying back the yen they were sold – resulted in upward pressure on the yen and downward pressure on the euro. Then in 2009, the US embarked on the first of several rounds of QE.

By contrast, the Democratic Party of Japan government, which came into power in August 2009 (defeating the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) government) was perceived as favouring ‘a hard yen'.

The BoJ governor Masaaki Shirakawa was viewed in global currency markets as an economist who, with his post-graduate training at Chicago University, was likely to follow a relatively orthodox policy. He seemed to take the view that temporary episodes of deflation could be tolerated and that Japan's economic problems mainly lay elsewhere. And in any case, although the BoJ in principle had been aiming for a long-run average inflation rate of 1% per annum ever since the early 2000s, it had never acted as if this was the top priority even during its QE episode.

The bank had made clear that financial stability concerns could in some circumstances override the long-range inflation aim even in the medium term. Hence, in the context of the Fed's QE policies and depreciation of the dollar from 2009 onwards, the yen gained attractiveness in the markets as a safe-haven currency. This was the one major currency where the central bank did not subscribe to the fashionable aggressive inflation-targeting doctrine.

Admittedly, the BoJ under Shirakawa gradually started to bend its policies in the direction of current monetary fashion, but it did so with obvious reluctance.

In October 2010, the bank embarked on its ‘comprehensive monetary easing' programme. This involved holding the short-term policy rate at fractionally above zero, forward guidance and an asset purchase programme.

Apart from relatively small purchases of corporate bonds, commercial paper, exchange-traded funds and real estate investment trusts, the asset purchase programme was confined to government bonds of less than two years' maturity; and it observed the rule that total bonds held should not exceed the amounts of banknotes outstanding. In global markets, all of this did not seriously dent the image of the Shirakawa's BoJ as a bastion of monetary orthodoxy.

However, the sky-high yen, which touched 76 in February 2012, 47% above its low in 2007, spread deep gloom in Japan's powerful export corporations and their workforces. And the LDP leader, Shinzo Abe, found appealing slogans with his promises of ending deflation and "promoting low inflation", increased government spending and higher wages for the so-called ‘salary-men' (leaning on the corporate leaders in the export sector to pass on benefits of yen devaluation to their life-time employees).

True, he spoke also of structural reform, but there was understandable scepticism about how substantial this would be (not very, as it has turned out). Ending deflation was widely understood as code for yen devaluation.

Alongside this was a nationalist message that seemed to resonate with voters concerned with China's increased military threat and apparent economic weight, which in turn made a story that could influence Washington favourably towards a policy of yen devaluation – one that it would normally oppose.

In fact, in this case, given that the policy was presented in the guise of fighting deflation – and putting Japan on the global 2% inflation standard, which the US and Europe had joined in the late 1990s – it was an objective shared with the Fed and more broadly with President Barack Obama's economic team. Clearly, US opposition would have been inconsistent. Washington welcomed the "bold counter-deflationary policy" in Japan on the basis that countering economic weakness there would be good for all even if the yen weakened. In late 2014 IMF managing director Christine Lagarde praised the "courage of PM Abe" in starting an intensified further round of QE aimed at "fighting deflation".

The Abe-Kuroda programme

Abe had made clear during the election campaign of late 2012 (he became PM at the end of that year) that he wanted to import a powerful version of America's QE policies into Japan. This change would be signalled by installing new leadership at the BoJ; in March 2013, Shirakawa was succeeded by Haruhiko Kuroda. Also appointed as a deputy governor was Kikuo Iwata – a critic of past BoJ policies. The BoJ committed itself to massive purchases of long government bonds with the intention of bringing down long-term interest rates further (they were already low at about 0.6%).

The Abe/Kuroda programme of introducing a high-powered version of US monetary policies in Japan called ‘quantitative and qualitative monetary easing', or QQE, so as to reverse the climb of the yen, followed a familiar script. Many times since the 1960s, the Federal Reserve had embarked on the path of excessive monetary stimulus: Keynesianism in the 1960s; Nixon price wage controls and Burns' election-winning monetary stimulus in the early 1970s; the Volcker policy of monetary easing in 1985-88; and the Greenspan-Bernanke policy of ‘breathing in' inflation of 2003-06. Each time, these policies triggered a big depreciation of the US dollar, notably against the yen.

Abe won a populist campaign in late 2012 on promises to fight deflation and boost government spending so as to achieve prosperity. Yes, there was a lot of talk about the ‘third arrow' of economic reform – but had not every prime minister of the last 30 years promised this? Market-watchers were not convinced that Abe was ready to confront entrenched interests blocking reform. The Abe programme aimed essentially at raising Tokyo stock prices in the hope that this would bolster consumer and investment spending.

Abe economics, or ‘Abenomics', was launched in early 2013, soon after the Fed had started its QE3 or QE ‘infinity' programme (on December 12, 2012, the Federal Open Market Committee raised the amount of open-ended purchases from $40 billion to $85 billion per month). The main effect was not to help Japan but to add more power to the asset price inflation virus in the global economy. Yield-starved global investors were all too ready to take on trust the story that Abenomics would bring about a Japanese economic renaissance. And, of course, many US academics queued up to praise the programme.

In December 2014, Abe called a snap election, two years earlier than the legal time-limit for the lower house of the Diet and giving the opposition less than three weeks to campaign – an affront to the normal standards of the democratic process. He also declared that the next sales tax increase, previously scheduled for 2015, would be delayed until 2017. The result of the election was not in doubt – Abe tightened his grip on power. (The German financial newspaper Handelsblatt described it as a victory for Keynes and a defeat for Japanese democracy.) Then in late 2014, the oil market crash started, bringing some good news at last for Japanese consumers whose real incomes had been squeezed by devaluation.

However, not surprisingly the economic outlook remains gloomy. Monetary experimentation has created huge monetary uncertainty. Asset price inflation inevitably makes households and businesses worry about the risks of a future asset price collapse. Prolonged suppression and manipulation of market interest rates have deprived investors and business leaders of key signals for the appropriate allocation of resources. In addition, the still remote but rising fears of great monetary storms in the future – even of a currency collapse – do nothing to spur capital investment in new plants and equipment.

Kuroda has defended QQE on the grounds that it can help to bring down term premia and influence expectations, boosting equity and other asset prices. It was also necessary to create new money en masse: "Since inflation is widely perceived to be ultimately a monetary phenomenon, the creation of a massive quantity of money would be a strong signal of a central bank's commitment to fighting deflation. It is in this context that an unprecedented expansion of the monetary base plays an essential role in our QQE."

Kuroda has also strongly denied that QQE facilitates fiscal expansion. However, this is a charge currently being levelled against the BoJ. Even the Organization for Economic Coordination and Development, an official body, warned in its economic survey of Japan in April 2015 "The recent expansion of QQE prompted concerns that the BOJ is being forced to monetise government debt, raising the risk of sustained yen depreciation and a run-up in interest rates that could undermine the financing of government deficits." it said in the OECD economic survey for Japan in April 2015.

In our view, Abenomics has added to the risks facing the economy without lifting it to a higher growth path – an unnecessary objective anyway, as its performance up to 2012, when adjusted to take account of divergent demographics, was better than generally thought and indeed compared well with that of the US. But viewed in long-term perspective, the Abe-Kuroda policies fit into a familiar pattern. Always, the challenge has come from sudden surges of US monetary expansion. Every time, the Japanese economy has suffered severe injuries from these violent monetary moves.

Eventually, under acute pressure from the accompanying exchange rate fluctuations, Tokyo has always responded in the same way. Again and again, the Japanese authorities have resorted to tit-for-tat monetary expansion. The medium and longer-term consequences have always been injurious. At present, a questionable reading of history is used to justify a policy that has increased rather than reduced the sense of gloom overhanging Japan's prospects.

An alternative to Abenomics

There was a grand alternative. The government and BoJ could have explained to the public that unstable US monetary policies posed a challenge to the Japanese economy and that to secure long-run economic prosperity, they would stick to the principles of monetary stability while asking the workforce to accept considerable flexibility in wages and prices, especially in the traded goods and services sector. A programme of sweeping economic deregulation was essential to meeting the challenges.

The programme would have included promoting an efficient market in corporate control, alleviation of impediments to new construction, removal of obstacles to entry in protected industries, tackling restrictive practices (notably in the retail and wider service sectors), loosening restraints on start-ups and venture capital, and ending financial repression. A supply side package would have featured cuts in marginal tax rates and in mainstream corporate tax rates balanced by cuts in government spending (in sharp contrast to the public investment spending bulge under Abe).

Equity issuance would have soared on cuts in corporate taxes, facilitating hostile takeovers and fostering a market in corporate control. In the financial sector, too-big-to-fail protection in the banking industry would have been scrapped, deposit insurance reduced and the postal saving system dismantled. Meanwhile, the growth of the yen as a global currency would have benefited Tokyo as an international financial centre. Sadly, it was not to be.

The authors acknowledge using source material from A Global Monetary Plague: Asset Price Inflation and Fed Quantitative Easing by Brendan Brown (Palgrave, September 2015)