Fake news has been in the news of late, and one might wish that news about fake news were fake as well. But it’s so real that recently in Washington DC a deranged gentleman emerged from a dark swamp on the internet and shot up a neighborhood pizza joint in search of the child sex-slave ring run, in its basement, by Hillary Clinton and John Podesta. Fake news has been around for a long time: Remember the supermarket tabloids with headlines screaming “Mom boiled her baby and ate her”? But nobody, to my knowledge, ever sought that lady out armed with a bottle of Pepto Bismol. The people who attended the wrestling matches I used to go to in my youth believed the stuff was real and often got into fights when their hero got sat on by Haystacks Calhoun. But that was the worst things ever got. Maybe reality TV, which isn’t real, has degraded our public sense of humor and skepticism. It certainly looks like the internet can make the most preposterous things believable to a considerable number of folks, and something is surely amiss when these cause bullets to fly.

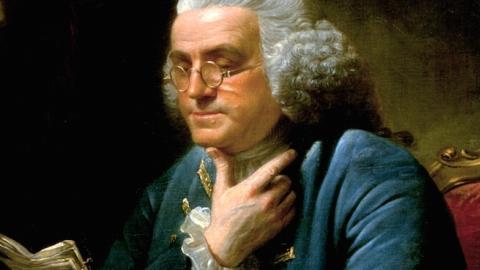

But before we get all agitated and obsessed with fact-checking and three or four Pinocchios, it might be helpful to consider if what we lack these days is really good fake news. That would require that we know what it is and where we might look to find it. Actually, the very first American newspaper tycoon—none other than Benjamin Franklin—was also the first master of the journalistic hoax and ridiculously false news. A sixteen-year-old Franklin started out his scribbling career in literary drag as Silence Dogood and in fourteen of “her” essays made merry fun of the Boston religious and political elites. (In her fourth essay Silence recounted a dream she had about “that famous seminary of learning,” Harvard College, which turned out to contain a gaggle of dunces, blockheads, and plagiarists.) Until just before he died, Franklin wrote and published anonymous and pseudonymous tidbits and essays depicting a myriad of bizarre human behaviors and beliefs.

In one he told the story of a man who, when his canoe overturned, wisely secured his fiddle and let his wife go to the bottom. In another he recounted a trial in which a mob used an “experiment” to prove that some witches had caused their neighbors’ sheep to dance strangely and their pigs to sing psalms. He made fun of a “Pythagorean-cynical-Christian-philosopher” who tried to make a testimony against the vanity of tea drinking by sacrificing his wife’s luxurious china, only to have the audience knock him down and make off with the cups and saucers. In 1730 Franklin published two hilarious spoofs in the form of advice-seeking letters to the editor: One letter came from a man torn between believing in spirits and miracles or being an adherent of “Spinosists, Hobbists, and most impious freethinkers.” The other letter came the next day from a man named Philoclerus warning the editor not to make such obvious fun of religion. As it turns out, for all the anti-clerical fun Franklin had indeed made, his Philoclerus gets the better of the argument as regards belief in spirits and miracles.

In 1747, Franklin published his most famous hoax, “The Speech of Miss Polly Baker.” In this spoof the prostitute Polly Baker, on trial for her fifth time for having an illegitimate child, convinces a jury that she had been innocent of adultery and tricked by her respectable first suitor when she was “still a virgin.” Rather than deserving a whipping, Polly argues, she should have a statue erected in her memory for heeding God’s commandment to be fruitful and multiply. Polly’s speech, depicting as it does the hard lot of women at the hands of men, is so touching and convincing that one of her judges married her the day after the trial.

At the height of the Revolution and while in Paris, Franklin wrote and published a hoax about a shipload of dried and hooped American scalps sent as a gift from Indian allies to King George. But he included in the hoax a letter from the Chief begging the King for relief from the Americans who have “great and sharp claws” and who intend to drive them from their lands. The war, Franklin knew, provided equal opportunity suffering. And just weeks before he died, Franklin in his very last publication wrote a hoax about the slave trade—intended as a spoof of a Georgia Congressman’s recent speech against congressional interference in the awful business. The hoax consists of a speech by one Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim, a member of the Divan of Algiers, against Muslim “purists” who oppose as a sin against God the enslavement of white “Christian dogs.” Franklin, who was president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, could write this hilarious piece in which both sides of the issue (Sidi and his co-religionist “purists”) claim that God and reason are on their sides.

These are just a few of Franklin’s always hilarious and always tellingly philosophic pieces of fake news. So, what is it that makes them all so good? What do they all have in common? They all depict and then dissect the many ways that human beings can be so credulous and crazy about just about everything that really matters in life. Sect and party: these were the facts of life that scared Franklin the most, because they never see both sides of things and especially because they are the angry and mortal enemies of humor. Franklin could and did make fun of everything he and his fellow Americans held dear. But he did so without malice and especially without thinking that he could never deserve to be the butt of his own humor. In his Autobiography, Franklin summed up beautifully the dilemma of his own and human pride: “For even if I could conceive that I had completely overcome it [pride], I should probably be proud of my humility.”

Benjamin Franklin was, if nothing else, a rationalist. But that said, he was not a partisan of reason (it’s hard to imagine him in a university faculty lounge). At one point in his young life he tells us, he became a vegetarian in order to save money to buy books, and later he became something of a “moral” vegetarian. That didn’t last long, however, because one day he came across a man selling fried fish and was tempted by the wonderful smell. He resisted, but then gave up his scruple when he saw little fish falling from the sliced gut of a larger one. If fish eat fish, he concluded, there is no good reason that he should not do so as well. Of this incident Franklin then made perhaps the most powerful observation of his life: “So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.” This is the lesson that Franklin taught with all of his fake news. Given our Republic’s now angry and gullible mood, we all could do well to keep this skeptical lesson in mind.