One hundred years ago, on Feb. 26, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson learned about the telegram that would pull the U.S. into World War I. The Zimmermann Telegram—a secret offer by Germany to help Mexico reconquer the American Southwest—not only compelled Washington to end a tradition of neutrality, but transformed the balance of world power for the next century. It’s a historical episode with important lessons as President Trump contemplates how to conduct international politics in the 21st century.

In 1914 Germany had launched its U-boat campaign, using submarines to sink ships without warning, including those from neutral nations. In May 1915 a German sub torpedoed a British civilian liner, the Lusitania, killing 128 Americans. Wilson threatened military action if it happened again, which forced Germany to impose restrictions on its U-boats.

As the war ground on, however, Germany began to view submarine warfare as its route to victory. By 1917 the German high command believed it could bring Britain and France to their knees in six months by sinking neutral ships and depriving the Allies of food and supplies. Yet the Germans knew this would arouse the ire of Wilson, who had won re-election only months earlier, running on the slogan “he kept us out of war.”

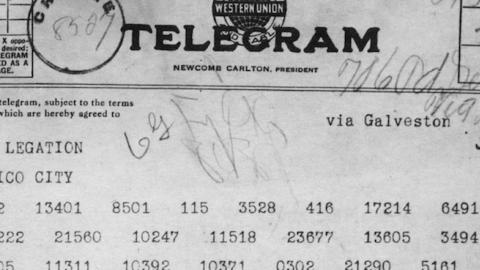

How to counter America’s potential response? On Jan. 19, 1917, Germany’s foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a coded telegram to his ambassador in Mexico. The ambassador was instructed to offer the Mexican president, Venustiano Carranza, an alliance: If America entered the war, Germany proposed that Mexico open a second front against the U.S. The Germans would then help “regain by conquest her lost territory in Texas, Arizona and New Mexico.”

In some ways, it was a clever move. Carranza was still smarting from President Wilson’s decision three years earlier to send an American force to occupy Veracruz, as well as Gen. John J. Pershing’s 1916 expedition against the bandit Pancho Villa. If there was a country in the Western Hemisphere ready to ally with Germany against the U.S., it was Mexico.

But if anything was set to turn American public opinion against neutrality, it was a secret plan to invade the U.S. The British, who had intercepted the diplomatic cable, knew this. So once they had fully decoded the Zimmermann Telegram, they made sure it landed on Wilson’s desk. They gave it to the U.S. ambassador in London on Feb. 24.

When Wilson released it to the public, the telegram rallied patriotic sentiment like nothing since the burning of the White House during the War of 1812. Yet the president remained hesitant. He still believed American neutrality was the best way to promote peace. Even after Zimmermann confirmed the authenticity of the message on March 3, Wilson waited nearly a month before asking for a declaration of war.

“It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war,” Wilson said in his historic speech to Congress on April 2, but “America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace she has treasured.”

He also insisted on the purity of America’s motivation: “We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion.” But to champion right against might, “we can dedicate our lives and our fortunes, everything we are and everything we have.”

And so they did. In 1918 more than 4.5 million Americans donned uniforms and turned the tide in Europe. By war’s end the U.S. had built a formidable Navy, second only to Britain’s. America emerged from World War I as a global hegemon, the center of a world economic and strategic order that World War II would only confirm.

What can we learn today from the Zimmermann Telegram? First, don’t underestimate America. In 1917 the Germans mistook self-restraint for weakness, and it cost them the war. Others would make the same mistake later: Japan and Germany in World War II, the Soviet Union at the start of the Cold War, al Qaeda on the eve of 9/11. Today Russia and China bid fair to make the miscalculation once again.

The second lesson is that conflicts will find America, even if America doesn’t seek them out. Just before his inauguration in 1912, Wilson remarked to a friend: “It would be the irony of fate if my administration had to deal chiefly with foreign affairs.” Yet two oceans didn’t make the U.S. safe from aggression then, and the danger is even greater in the age of ballistic missiles and cyber-attacks.

Wilson imagined he could keep the U.S. safe by staying aloof and above the fray. It took an intercepted telegram for him to realize that America had no choice but to act as a great power. One hundred years later, Mr. Trump should remember that Wilson’s realization has made the world—and us—safer.