In its first hundred days, the Trump administration has taken a very welcome hardline stance on North Korea. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s repeated warnings to Pyongyang about its ballistic-missile threat during his recent visit to South Korea, Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s dispatch of the supercarrier USS Carl Vinson to the area, and President Trump’s own statements all reveal an administration that understands it’s time to confront Kim Jong-un head-on, rather than coddling or ignoring him as President Obama did.

Trump also understands what has been obvious to many of us for years: The path to Pyongyang goes through Beijing. Trump’s strategy of putting pressure on China’s President Xi Jinping to sever support for Kim is smart, and it seems to be yielding some results. In February, Beijing curtailed coal exports to North Korea. More significant, a Chinese official has told the Nikkei news agency that China will move to cut off oil supplies to North Korea if the North tries another nuclear test. This is a good first step, but the Trump administration must try to force Beijing to go further, demanding that China cut off those oil supplies that are vital to North Korea’s military if Kim conducts any more intermediate- or long-range ballistic-missile tests or refuses to allow U.N. inspectors entry to its nuclear sites.

In short, America’s overarching strategic goal should be to tighten the noose on North Korea by keeping the pressure on China to make its vicious client state behave. That, of course, can’t be accomplished in the long term without a coherent, sustained diplomatic strategy. But fortunately, in the short-to-medium term, the technology is at hand to deter Pyongyang from threatening its neighbors with nuclear attack ever again.

Right now, we have to rely on land- and sea-based missile-defense technologies such as THAAD and AEGIS to protect South Korea, Japan, and America’s regional bases from North Korean missiles. The problem is that these systems only shoot down an incoming ballistic missile as it reenters the atmosphere toward the end of its flight, which narrows their margin for error; if the interceptor misses or intercepts a nuclear-armed missile too close to a target such as Tokyo or Okinawa, the result could still be catastrophic.

A better option is stopping a North Korean missile launch much earlier, in its boost phase. Any large multi-stage rocket requires high-thrust booster engines to get out the atmosphere, boosters which then drop away when the missile achieves orbit. Destroying a missile in this early boost phase has all kinds of advantages. Since it’s the hottest stage of a ballistic-missile launch, it’s the easiest for long-range infra-red sensors to detect and identify. And it’s also the slowest phase of the launch, so the missile loses any advantage it might have in terms of speed in its later descent.

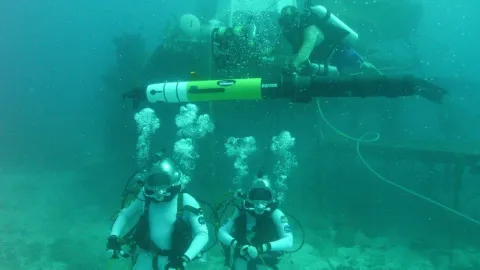

A BPI intercept can’t be done from a ground- or sea-based BMD system; THAAD or Aegis can’t detect the launch soon enough. But an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), stationed 350 miles outside North Korean air space at an altitude of 50–55,000 feet and equipped with infra-red sensors and conventional anti-missile ordinance of 225 KG, could bring down even a large ICMB in its boost phase. Once the launch is detected, the UAV’s on-the-ground operators would have nearly a minute to decide to intercept given the speed of North Korea’s missiles — more than enough time to initiate the kill chain.

What’s more, a boost-phase intercept comes early enough in the missile trajectory that any debris would drop into the Sea of Japan, or over North Korean territory. Even a submarine-launched missile — when Kim tested one of those last August it traveled more than 300 miles and crossed into Japan’s Air Defense Identification Zone — can be picked up immediately after launch by a UAV, something neither THAAD nor AEGIS is capable of.

If this sounds like science fiction, think again. There are already American-built UAVs capable of carrying up to four interceptor missiles of this size, while conventional aircraft have successfully done BPI tests using missiles of this type. Putting those missiles on a rotating UAV patrol off the North Korean coastline would mean round-the-clock surveillance and detection that provided an extra layer of security from missile attack.

The deputy director-general of our own Missile Defense Agency has said that BPI is the next goal for missile defense. Dr. Leonard Caveny, the former science and technology director for the DOD’s Ballistic Missile Defense Organization, has estimated that a proof-of-concept BPI launch would cost no more than $25 million and could be ready in less than two years.

Between keeping the pressure on China and deploying unmanned BPI, the Trump administration could bring the world closer to a major achievement: taking away Kim Jong-un’s principal tool for threatening the region and stirring up international mayhem.