Following is the full transcript of the July 18 Hudson event Conversations on National Security and U.S. Naval Power: Rep. Joe Courtney and Seth Cropsey.

KENNETH WEINSTEIN: Good morning, and welcome to the Betsy and Walter Stern Conference Center here at Hudson Institute. I'm Ken Weinstein, president and CEO of Hudson Institute, and I'm delighted to welcome everyone to the second event in our newly inaugurated speaker series, Conversations on National Security and U.S. Naval Power. This series, which Hudson senior fellow Seth Cropsey, who directs our Center for American Seapower, runs, is designed to be a forum for critical voices who champion the notion that maintaining American maritime pre-eminence is essential to American national security. In this vein, I'm especially delighted to welcome Congressman Joe Courtney of Connecticut's 2nd District to Hudson Institute. Congressman Courtney has served for six terms in the House, representing the 2nd District. He serves on the Armed Services and Education and Workforce Committee. His is an important voice on naval issues as ranking member of the Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee and he is co-chair of the House Shipbuilding and Submarine caucuses. I think there is no better voice for strong bipartisan support for the U.S. Navy than Representative Courtney.

He's been a leader on numerous issues, including on pushing for increased submarine production as a national security priority. And he's championed an issue near and dear to our hearts here at Hudson: the need to replace the Ohio Class of submarine. I should note that the largest military installation in New England, SUBASE New London, is in his district, as are the Coast Guard Academy and the Electric Boat shipyard. And for his important work on national security promoting the U.S. Navy, he's received the Distinguished Public Service Award from Navy Secretary Ray Mabus, the highest civilian honor the Navy confers.

Representative Courtney is going to be in conversation with Dr. Seth Cropsey, whom, as I noted earlier, directs our Center for American Seapower. Seth is a student strategy in history and a keen observer of strategic naval developments. He's a two-decade veteran of the U.S. Navy who served as deputy undersecretary of the Navy in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administration. And he's the author of two must-read books: Mayday: The Decline Of American Naval Supremacy, which came out in 2013, and its 2017 sequel, as it were, Seablindness: How Political Neglect Is Choking American Seapower And What To Do About It. Seth is, of course, a frequent contributor to the op-ed pages of important newspapers, including The Wall Street Journal. So without any further ado, let me turn it over to Seth. Thank you very much, Congressman.

SETH CROPSEY: Thank you, Ken. Representative Courtney, thank you very much for joining us today. It's an honor for us and looking forward to the conversation. The congressman should leave – because of the schedule in Congress – at about 12:45, give or take a couple of minutes. I'd like to wind things up a few minutes before that so that there'll be an opportunity for questions and answers. So let me get to it without delay. I guess most important question here is: why is seapower important today? What is the challenge that faces the United States at sea globally? And that would be good for starters.

REP. JOE COURTNEY: Sure.

CROPSEY: What's the issue?

COURTNEY: Well, first of all, I want to thank Hudson Institute for the invitation. And it's good to see you again, Seth. He's been a witness before the Seapower Committee over the years and, again, really solid, experienced input, which has certainly been valuable over my time there. And again, it's great to be with you here at this forum.

So on the committee this question gets asked frequently. As Ken said, I'm in year 12 now. And to some degree, the answer has sort of shifted a little bit in terms of just what's been happening out in the world. I remember, as a freshman on the Armed Services Committee, General Pace – the chairman of the Joint Chiefs – and I were asking him about the decline in the submarine fleet. At the time, we were in the height of Iraq's ground war, and he just sort of looked at me a little askance and basically just said, “Well what are you worried about, China?” You know, like that was something that was far-fetched at that point. But obviously, the world has changed. That question gets asked a lot differently now.

And the answer certainly is clearer today than it was to some folks 12 years ago. And obviously we get a chance to go out and visit areas like Indo-Pacific. We've been with Admiral Harris a number of times, who describes what's going on in terms of the change of the international order, and in terms of sea lanes and the maritime environment. Again, the 70-year reign of freedom of navigation, which I think did so much to boost wealth – growth – across the world, obviously is now very much in play because of China's, I think, extralegal – illegal – claims in terms of controlling the South China Sea and even the East China Sea – the island building. This isn't just an ego trip, in my opinion, in terms of that country. They really are trying to change what I think has been a very successful 70-year record of peaceful rule of law that existed in the maritime realm. And that's why certainly our conversations at RIMPAC with some of our allies – Australia had their Australian-American Leadership Dialogue in town here last week. Again, this whole issue of maritime freedom of navigation is really changing in real time, to the point where all of our allies – whether it's Australia, Vietnam, Japan, Philippines – are all looking at their naval budgets, because they realize they can't take for granted the environment that existed before. I mean, if you shift again to the Atlantic, it's a totally different environment than 12 years ago when I first came to Congress. And General Scaparrotti and the European Command has been emphasizing those points when he's come to committee that submarine activity and aggressive behavior on the seas are just radically different than they were 12 years ago. And that's where I think that our country has a very important role to play in terms of trying to restore what I think were very successful international rules of the road and norms that benefit everyone.

CROPSEY: We'll get back to China in just a moment. But you mentioned the Atlantic. And I was wondering, what about the Mediterranean? Which is to say, we have four ballistic missile defense destroyers based in the western extreme of the Mediterranean, but that's a relatively quiet area. And the eastern end of the Mediterranean is a relatively unquiet area.

COURTNEY: Now, again, this is new stuff, in terms of what existed 10 years ago. And, you know, we may as well throw the Black Sea in there as well, and Crimea – the annexation by Russia, I mean. At the end of the day, it was really as much a naval play as it was sort of a territorial play. And, you know, that...

CROPSEY: Because Russia didn't have a port on the Black Sea fleet.

COURTNEY: Correct. So, the map is changing, as I said, in real time. And certainly what you described in the Mediterranean could probably keep going around the world in terms of the Indian Ocean and other places that the whole issue of the maritime realm looks a lot different. And I think the Navy's role, which was somewhat reflected in the national defense strategy that the administration put out, is in a much different place than it was a decade ago.

CROPSEY: Let's go back to China for a second. Just want to throw out some statistics here. The Naval War College's Chinese Maritime Study Institute predicts that the Chinese combat fleet will reach well over 415 ships in just 12 years. For example, the PLAN, the Chinese navy, is developing air independent and nuclear submarines and ballistic missile nuclear submarines. And in just the air independent propulsion class submarines, they're going to put 20 boats in service between 2006 and 2020. And just because they're air independent propulsion vessels – boats – doesn't mean that they have to stay within the immediate neighborhood. In fact, some of them have deployed as far west as Pakistan. The Navy – our Navy – expects the Chinese submarine force to reach 70 boats two years from now and 99 by 2030, when we're supposed to have – if the current shipbuilding plan stays in place – 78. Are we going to be able to keep pace with the Chinese navy? You've been at the forefront of calling attention to the need for increased U.S. submarine shipbuilding in the foreseeable future. I was wondering if you could tell us about that.

COURTNEY: Sure. So we have the opportunity to hear directly from our combatant commanders in different parts of the world. Admiral Harris in the last two or three years has been incredibly blunt and to the point about the fact that this environment is changing rapidly. And the numbers that you recited really, I think, underscore that. And so it's having a lot of ripple effects. Just to get out of the submarine realm, I mean, I actually think the ship collisions that occurred there are fundamentally being driven by the heel-to-toe sort of deployments of our surface ships in response to this increased activity. That's obviously resulted in a much larger sort of analysis in terms of balancing safety with the pace of deployments. But it's all tied to that same area.

And, you know, we obviously made a decision – it was either at the end of the Bush administration or beginning of the Obama administration – to change the proportion of the Navy's presence to 60-40 in the Indo-Pacific region versus the European area. At that time, we weren't seeing the resurgent Russian navy happening, so it seemed like a pretty safe bet at that point. And so what I would say in terms of the positive side is that the force structure assessment that came out in December of 2016 – which talked about a 355-ship Navy – and within that also made some – I think – pretty significant statements regarding the composition of the fleet architecture. All of that was not just done in a sort of wish list. It was really done as a result of strategic challenges that are changing out there, which you documented well. And so, you know, that's a very good framework that the U.S. should be working from in terms of the future of the Navy. But it still begs the question of how fast and where we are actually spending our money. Does it really align itself with the force – the fleet architecture – that was recommended in that report? And that obviously has been an issue that was just played out on the floor of the House of Representatives just a couple weeks ago. And I think there's serious questions about whether or not we're off to a good start in terms of implementing that force structure assessment. So far I would give pretty low marks to what's happened in the year and a half since that report came out.

CROPSEY: What should we be?

COURTNEY: Well, the thing I've learned on the Seapower Committee is – and you know this and most of the audience does – that shipbuilding is a long game. It’s great to have a report that says we need to go from 308 to 355. But the fact of the matter is that if you look at the length of time that it takes to build a carrier or a destroyer or a submarine, this administration – even under the best-case scenario, if they get to a second term – I mean, they're already a quarter of the way through in terms of what impact they can make. And so far, if you look at the 30-year shipbuilding plans that have come over from the administration as well as their budget, we're in the breakdown lane in terms of how speedy this implementation is going to be. And so what our committee has been doing – and I don't think it's far-fetched or pie in the sky – is we have been working with the Congressional Budget Office, with the Congressional Research Service, with the Navy, to really try and come up with the most efficient ways to maximize precious budget dollars and authorizations to really get ahead of the curve in terms of implementing the FSA. And so far there has been a lot of resistance – institutional resistance – within the OSD, the Office of Secretary of Defense.

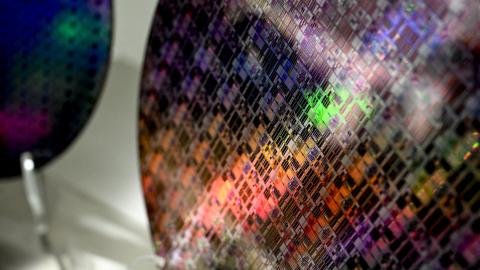

The Navy has, in my opinion, given us very good tools to look at and to work with in terms of, you know, a two-carrier block buy. And we've gotten information that will save money for the shipbuilding account. In the area of the Virginia Class, Admiral Merz and others, when they came over last February with their 30-year shipbuilding plan, they identified industrial-based opportunity to go above a two-a-year build rate – not too fast, not too reckless or rash – but in 2022 and 2023. And they also gave us what we need to do in terms of long-lead acquisition to make sure that the industrial base can meet that growth in a way that is orderly and going to be implemented. Obviously, there was big pushback two weeks ago from OSD in terms of those proposals, which I think is very unfortunate because, as I said, we are going to be in a place where, to use the SSM, the attack submarine fleet, which is at 53 today, it's going down to 42 over the next 10 years, with the retirements of the Los Angeles Class. That's happening at precisely the same time that we're seeing our competitors growing that size of their fleet, as you pointed out. So, you know, the NDAA, which you and I were talking about off camera here, is in the process of final stages. We're still trying to create some legal space for the Navy and the ship builders to take advantage of what Admiral Merz identified back in February, because if we don't do that, then we're really just going backwards in terms of what the FSA laid out. And as I said, in terms of what we're hearing from the combatant commanders, and certainly what our intelligence are telling us in terms of where the growth is, we're going to be hard pressed to sort of keep up with these challenges that are out there.

CROPSEY: I just want to harp on that point for a moment, because it really deserves harping. Because of the retirement of submarines that are outliving their service lives and our ability as it is right now to replace them, there's going to be a decade gap when the size of our submarine force does not increase. To mention the most obvious example, China is not bound by that problem. What are the consequences? I mean, when you talk with combatant commanders, I mean, I'm sure you asked the question. What...

COURTNEY: Well, I mean, what they tell us is that, at some point, quantity is quality. If you are out there and your competitor is in bigger numbers, the best you can do is play zone defense, and that's really not the optimal situation to be in. And, you know, Admiral Foggo, who's over in Europe right now as the head of our naval forces, has been publicly talking about the fact that submarine activity now is really starting to get close to Cold War levels: you know, 70, 80 percent. Stavridis testified before our committee to the same effect. So it creates higher risk. And as I said, that's where we are today, with that decline that is just baked in, just because of the reactor life and the hull life. You know, the only way you can mitigate that – and again, we'll be watching the president's budget in February when it comes over – is whether or not service life extension becomes the mitigating policy to try and reduce the size of that bathtub that's going to be happening in the 2020s. But service life extension, which is – I'm not religiously opposed to that, but it creates its own set of issues that you really have to think through. These are old boats. I mean, they were built in the 1980s and '90s. You know, they don't have the same capabilities that a Virginia Class has. And when you have to refuel the reactor, which is what you have to do for a service life extension for a Los Angeles Class, and you've got to really check the hull to make sure that it's OK. They've been running hard for the decades that they've been out there. And then there's a whole separate issue. Technology's changed in terms of shipbuilding. Where you get spare parts, where you find the prints because you didn't have computer-aided design back in those days – this thing is not as easy as it sounds. It's not like putting a quart of oil in your 10-year-old car and hope it'll run for the next five years.

CROPSEY: That'd be some quart. Is it your sense that your colleagues outside the Armed Services Committees see what you see? Or is this an issue that is one of many and you have a lot of things to do? I mean, where is Congress here?

COURTNEY: Well, I would say this. As I said, compared to my question as a freshman versus today, it really is different. I mean, people do understand in a pretty broad-based way that the world is in a different place and that – again, if you look at the FSA, just for the record, was issued by the Obama administration, I mean, that was Secretary Mabus who – and it wasn't just in response to the election in November. I mean, this thing had been ongoing for about a year and a half. And if you look at the record of that administration, they actually doubled the number of ships under contract. So there has been a trend that even predates the new administration that has been moving towards recapitalizing the Navy. And it's been pretty noncontroversial in terms of defense appropriations bills and DAAs.

But the more recent challenges which you described are still sort of starting to sink in. And so when we had the debate on my amendment a couple of weeks ago, which would have implemented the long-lead materials to get to a three-a-year build rate in '22 and '23 for the attack subs, one of the members in the opposition got up and said, “Well, we have a very good shipbuilding plan from the administration that will get us to 355 ships by the 2050s, so I think that we need to kind of work on that.” And it was said very sincerely. But that’s 32 years from now. So even with the people who are in the middle of the debates on this, the risks of waiting that long and also not focusing on the components of the FSA, I think are just – really, we've got more work to do.

So, I want to just touch on that point for a second. You know, 355 is a great number, but if it's 355 small combatant surface ships, that doesn't really address the strategic challenges which were driving that report. If you look deeper into the report, it actually talked about increasing the submarine fleet from 48, which was the target from the prior force structure assessment, to 66 SSNs – attack subs. And the large surface components went up by 14. Well, if you look at the budget that came over the 30-year shipbuilding plan and what's coming out so far in the appropriations process, those components of the fleet really don't get the attention that the FSA was pretty vigorously pointing...

CROPSEY: Fleet structure assessment, when you say FSA.

COURTNEY: Yeah. Sorry. Yeah.

CROPSEY: And, as you know, I wanted to just make this point for people who joined us today: both the Congressional Research Service and the Congressional Budget Office agree on numbers, that the shipbuilding requests would have to be something like 20 to 25 percent higher than what we've seen, even from this administration, sustained over that 30-year period or a 30-year-plus period just to reach the 355 ships. So that means an agreement between the executive and the legislative branches to sustain shipbuilding at a rate that's 20 percent higher than the average of the past three decades in order to get there. So...

COURTNEY: That's true. And obviously, it raises a larger question of how the pie chart gets divided up in the Department of Defense as a whole. But I want to emphasize that CBO and the Congressional Research Service have also done really good work about trying to identify ways that we can more efficiently build more ships and boats and subs, which is incremental funding, which is an appropriations term. But that allows you to basically shop like you're at Costco, where you can use higher-volume ways to – materials and suppliers. But again, it means you got to get out of the one-year budget cycle and look at some of these programs over a period of time. To the extent that there is new programs, that's probably unacceptable risk in terms of whether or not a new ship should really get that kind of, you know, carte blanche – or I wouldn't call it a blank check – but certainly freedom to purchase over a period of times.

But when you're talking about Virginia Class, this is a program that has now demonstrated its credibility as a successful program that has been really hitting the targets in terms of 60 months for construction and certainly staying at or within budget. So why you would not want to take advantage of that success with incremental funding – you can buy more subs for less money if you do it, you know, like a Costco approach to acquisition. And by the way, we've been doing that with carriers, because they're so expensive and they're so big. You have to do incremental funding for carriers. So it's not like we're violating some orthodoxy or catechism by having the DoD and the appropriators embrace more efficient ways to build. And as I say, it's gotten the blessing of CBO and CRS in terms of our work with them.

CROPSEY: And it's worked before. I mean, at the beginning of the Reagan administration, two carriers were funded at the same time. And the Navy, I think, estimated that the savings amounted to over $700 million, which, in that time, was actually a serious amount of money.

Let me just switch topics for a moment here – switch direction. What's your sense of whether the United States has a maritime strategy today? Are we drifting? Are we moving ahead purposefully? Are we deliberating? I mean, we've been talking about ship numbers and types of ships and their importance and the threat. But if all of those things go as they should, that needs to be accompanied by some kind of idea. How are these to be used? How do we match the resources we have with the challenges that we face?

COURTNEY: That's a great question. So the former maritime administrator, Chip Jaenichen – who, with the change of administration had to leave –, he was valiantly working on a maritime strategy report for the country as a whole, which extended beyond just the Navy, but really also all the auxiliary and support services for the Navy as well as the Coast Guard and commercial shipbuilding. We have not had a maritime strategy since the Roosevelt administration that really has looked at things in a sort of global way, which would, I think, be a pretty logical, obvious step for a maritime country, and I know you've argued this with your book, Seablindness – you know, your work in the past. Chip left office without being able to get across the finish line with the report. It was really interesting talking to him about it because he said, you know, how to try and get to that place with all of the federal agencies that touch, you know, the seas and the maritime realm was like dozens, you know? And trying to get them all – herd these cats together so that we could have a comprehensive maritime strategy – at the end of the day, he just couldn't make it all come together.

So Admiral Buzby, the new MARAD administrator, we've had some great meetings with him. I think he wants to try and continue that work. I really think it's such an important step for our country to take. By the way, it would be really good for our economy if we had a coherent picture about ways to live more productively with our really blessed position, in terms of being in the Atlantic and the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico and even some of the big interior bodies of waters. And the absence of that, I think, is one of the reasons why commercial shipbuilding almost disappeared over a period of time, because no one was looking at it in a coherent way. I don't think that's true of some of the other maritime countries in the world. I think they had very focused, strategic attention that they were paying to that, and as a result, we're seeing technology and ships being built in other parts of the world that, frankly, we can do it, but we just don't have the organization to get there.

CROPSEY: Look, I really appreciate your insights, so we can talk a little bit more about that. Why does commercial shipping matter on a strategic level? Why do merchant ships make a difference? What should be done?

COURTNEY: Yeah. I mean, part of it is an operational need. I mean, you know, the logistics of our military require having auxiliary ships that can transport people and supplies and etc., so I mean, that's sort of an obvious basic level. So again, I come from Connecticut. We're an aerospace state, in terms of Pratt & Whitney and Sikorsky. And you really do see having a book of business that doesn't just sort of concentrate it just in the military realm actually makes the health of the workforce and the research and development and the competitiveness of these amazing enterprises stronger. You know, if Pratt & Whitney is making the geared turbofan for commercial airliners that is about fuel efficiency and lighter materials for aircraft, that spills over and benefits in the military line of work that they do. Or if there's a downturn in military orders because of some budget cycle, having that commercial end of the business keeps the doors open and keeps people working. So I really think having a better balance of commercial and military in the maritime shipbuilding realm, I think, is just – you would see the same benefits. There's some instances of it. General Dynamics – you know, the NASSCO shipyard out in San Diego – do do some commercial and obviously do some of the Navy's other work out there as well, and you see there's a synergy there that really helps both sides when you have that balance. That's not just all concentrated in one sector.

CROPSEY: And by the way, you were mentioning some of our competitors around the world. China is not a bad example. And I'm not saying that China is better or that they have the right answer, but they certainly are moving in that direction. I mean, they have a large merchant ship fleet – what is it? – eighth or something largest in the world. They're building a blue-water force that can protect the sea lines of communication over which their merchant ships travel. And they're making large investments all over the world – from the West Pacific to the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean to the Caribbean – in port facilities; they’re putting large amounts of money there. So this may just be laissez faire at work, but I don't think so.

COURTNEY: And some of that is being sold into the U.S., by the way. The BAE shipyard in San Diego just purchased this massive dry dock from China, which, unfortunately, they couldn't find any other place to have it built. And I mean, it's kind of strange to have U.S. Navy ships in a dry dock that was built just within the last few years by China. So that capability is something that we really need to start looking at much more intensely. Yeah.

CROPSEY: Again, because our time is limited, I want to sort of jump around here a little.

COURTNEY: Sure, yep.

CROPSEY: But the accidents with surface ships that took place regrettably last year had national attention for some time – several weeks. Are you satisfied that the changes needed are being made, and that the issue has been addressed, and that things will get better or that we won't see a repetition of that again?

COURTNEY: So again, just – you know, Connecticut lost two sailors in those two incidents, so it was something that was, you know, very – you know, these amazing young men and women come from every state in the country. And so it really hit hard up in New England when that happened. And so, what I would say is, No. 1, I think the Seapower and Readiness subcommittees really, I think, were very serious and persistent in terms of the process of briefings and hearings that took place in the wake of it. It was not a one-off media event. I mean, we've really been sort of trying to stay on top of this. And I think Admiral Richardson and Admiral Moran have produced serious documents. And there's about four or five different reports that are occurring. Some of it's just sort of the police kind of investigation of the actual minute-by-minute. And then, obviously, there's the comprehensive review, and then Secretary of Navy Spencer's review.

And so I think there's been a lot of changes that have already been implemented internally with the Navy in terms of really trying to just make sure that we're not sending ships out there – where people are certified with basic capabilities and competencies, which was not the case. It's almost sickening when you read the minute-by-minute account of what happened, and some of the sailors who had not been trained up on some of the new equipment that were on board those ships, which never should've happened. I mean, these were preventable issues or incidents that took place there. So I think that there already have been some changes that are happening. But your point about “has it been dealt with?” – this is not going to be a done process for, I think, years. I mean, there really are some changes that you just can't implement overnight. I mean, the fundamental question, which we've been wrestling with in NDAA and with the House and the Senate – and certainly talking to Admiral Richardson – is just this question of: who decides? Who makes the decision about when a ship gets deployed? And, as some of the audience knows, it's different in the Pacific fleet than it is in the other parts of the Navy's operations. And that's been a real tug of war, in terms of trying to make sure that there's a safety break here, that if there's really people who are not certified to operate a ship that, you know, the persistent demand that's out there, which we talked about earlier, is not going to override what I think really should be a fundamental priority, which is safe operation.

CROPSEY: Well, that's related to my follow-on question here, not directly but indirectly. And that is that the pace of the Chinese navy's operations in the Western Pacific has picked up recently, especially around Taiwan. I mean, and I mean around, literally, Taiwan. Are we doing enough? Are we responding in a way that you think is convincing? Do you think the Chinese – the Chinese navy, the Chinese leadership – are impressed or not impressed? What's your sense?

COURTNEY: Well, yeah. I can't really speak specifically to what's happening in the straits in Taiwan per se. But I think that starting in the last administration, and it's been continuing with the new administration, about the freedom of navigation – the FONOPs operations that are happening out there, I mean – I think that is still an important message that's being sent to the Chinese, that we don't need to ask your permission for innocent passage in this part of the world. But clearly, because of the challenge of quantity – you know, whether or not that's sufficient to really drive home the point and change the attitude – I don't think that's happened yet.

What would be a good thing, I think, is if we can sort of start getting some of our allies in the region to join us in some of those deployments and operations, so that once you get a regular stream of traffic in South China Sea and near these islands – it's clear that they're just going to continue – then I think you really start changing the dynamic. And that's something that Secretary Mattis and others have been really trying to encourage our allies to join us in. And I think that we still have a lot of allies, and they are boosting their navies that are out there right now. And so I think we hopefully can really organize that on a multilateral basis. Personally, I think we should ratify the Law of the Sea Treaty, which the fact that we were shut out of the deliberations from the U.N. conference – when Philippines filed that, we couldn't even get observer status there at that proceeding. To me, it is so overdue that we just get off the bench and get in the game, in terms of using international law more aggressively. It just screams out for this country to just finally do it.

CROPSEY: Though we are abiding by...

COURTNEY: Oh, no. It's true. But I still think – and Admiral Harris, when he testified before the committee, he said it would clearly take away one of China's arguments. Because really, when the ruling came down and we started raising our voice about it, they said, “You're not even a member of it.” So we should really get rid of that. And frankly, I think it would be a good message to our allies.

CROPSEY: We could continue and I hope that we shall. But time is short. And before opening the floor to questions, would everybody, when we conclude here, stay in your places for a moment to let the congressman and his group leave so that you can get to your next...

COURTNEY: Yeah.

CROPSEY: OK. So we'll try to be fair here and start in the very back. Sir, and if you would, would you please identify yourself and what organization you're with?

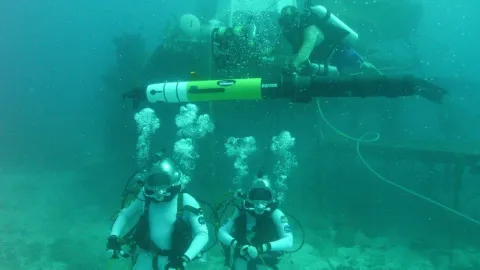

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Sure. My name's […]. I'm a writer for […]. Congressman, while we're meeting here in Washington, the RIMPAC exercises are taking place in Hawaii. I was curious of what's your opinion about the exercises? You talked a little about the U.S. allies and partners. You have Sri Lanka, India, Peru, Japan often taking place in the exercises. What do you think about it? What do you think about the fact that China was actually disinvited from the exercises after participating in the 2016 and 2014 versions? Thank you.

COURTNEY: So you're right. It's ongoing right now. I was able to attend the last RIMPAC. And I think it is just a refreshing example of U.S. leadership. You know, these days, we're all sort of trying to get our sea legs on, to use a bad pun. But watching the interaction of our Navy leadership with – I think the last count was about 25 different countries that participate in it. And again, it is really about reinforcing international norms – freedom of navigation. You know, my experience when we visited some of the ships out there, was that it was not this heavy-duty, militaristic sort of message. It really was about collaboration and talking about things like life saving and protecting as much as it is about any kind of territorial aggressiveness.

So China was participating during the visit that I was there. And it was really interesting because we visited a U.S. littoral combat ship when we were there. And the day before, there was a group of sailors on board the ship who actually visited a Chinese frigate. And it was a kid from Maine who was the only one from New England that I could find to talk to me there. But anyway, he was a great guy. And I said, “So how was it? You know, I mean, you should, like, keep a diary of this. I mean, that's a big deal, you know.” And he said, “You know, it's just another – they were just sailors.” They were sort of comparing each other's, you know, badges, and they needed an interpreter. But the officer there was basically making a comment that we learn more than they could learn by having that opportunity to go visit some of these ships and observe them in operation. So you know, clearly some things have happened. There's been intervening events that explain why Admiral Richardson changed that position regarding China. But I know it was done with a lot of, you know, pros and cons, in his own mind, in terms of whether or not we were actually giving up some benefits by having them participate.

CROPSEY: Yes. I see that there are a few questions. The woman – yes – in the second-to-last row there.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Hi, […] with the […]. The current administration has effectively lifted most of the pressure on Bahrain to implement human rights and democratic reforms, which overall threatens to increase instability in the long run and raises a risk to the U.S. Fifth Fleet base there. Is Congress or the Navy taking steps to mitigate this risk and encourage sustainable reform in the kingdom?

COURTNEY: All right, thank you. Well, I did have a chance to visit Bahrain. And there were actually protests that were going on while we were there. And it was a big topic of conversation, obviously, with our Navy leadership during that visit. And I think that this is an issue that we can't just look the other way, if we really want to have an enduring presence in that part of the world. And I think the change in policy is unfortunate, because, frankly, whether you are sympathetic to the people who are protesting and – they're certainly in terms of the population, I don't have the precise numbers, but it's at least equal if not even more, in terms of the part of the population that's unhappy with the ruling group that's there right now. I still feel like that instability is not healthy for what I think is a really critical base for the U.S. Navy. So I think that we really should revisit that change if we're really serious about an enduring presence there.

CROPSEY: And we'll switch back to this side here. Sir.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Thank you. […] from […] China and also […]. And according to One-China principle, I think China's Taiwan and mainland should adhere the same (unintelligible) and also maritime. Do you think so? And the second thing is about – the U.S. has sent a lot of municipal signals to Chinese sites. And U.S. has disinvited China's activity to the IMPACT and also defined China as particularly a competitor at the same time your (unintelligible) China. And I wanted to know how bad is the future of the relations between U.S. and Chinese navies, and is there possibility of conflicts or cooperations between the two navies? And can you specify it? Thank you.

COURTNEY: So I think that if you put our Navy leadership on truth serum (which they don't really need because they speak honestly all the time) – I mean, I don't think anyone relishes any kind of conflict or unnecessary risks of conflict occurring. Having said that, I think that the policies that are being implemented in terms of island building, asserting territorial waters that are just way outside any kind of international law or norms, creates real problems that are just going to aggravate risk. And so I feel like our country could do more in terms of upholding international law by just ratifying the Law of the Sea Treaty. But as Seth pointed out, we certainly have a very strong consistent policy of respecting and obeying the norms that the Law of the Sea Treaty creates. But I personally feel that the ball is more in China's court about whether or not they want to reduce risk in that part of the world. And I don't say that just as a U.S.A. position. I mean, we do communicate on the committee with a lot of other nations that are in that region. And they are very dissatisfied with the approach that's being taken in the maritime realm in that part of the world. I mean, they obviously have a front row seat to it, so they feel those risks much more acutely. So I think that if we can get to a point where people can sit down and start talking these things through, that's better than playing chicken out there on the high seas.

CROPSEY: We'll switch to the other side of the room here. Front row.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Thank you, reporter from […]. I have two questions. Congressman, you mentioned that China has increased its naval power building. So my question is: has China's naval power buildup successfully changed the balance of power in the South China Sea area? And if there is a conflict or a war breakout, can the United States definitely win the war? Second question is about the FONOPs. You mentioned that under this administration, the FONOPs have become more regular, and we have the allies there too. But it seems to me that we cannot stop China's militarization of the islands in that area. So can the United States do something more efficient to stop that? Thank you.

COURTNEY: So, I mean, on the first question, there's just no debate about whether or not China has expanded the size of its navy. They obviously have made big strides in terms of technology, missile technology, space technology, cyber technology that, you know, are much different than 10 years or so ago. And so my opinion is that it's definitely a more challenging place, if you're just looking at it strictly from a sort of military-versus-military scope. But my personal opinion is that we still have stronger capabilities to overcome any, you know, if there was any conflict that was there – you know, because your question was very blunt. I still have a high degree of confidence in that.

So, for example, their submarine fleet: the numbers are growing, as Seth pointed out, but they don't have the decades of experience that the U.S. Navy has in terms of operating in the undersea domain. And that still is a very strong advantage to our side. I still think the Virginia Class submarine program in particular has capabilities that really – even though we can't match sub for sub necessarily – I still think that I would tip the advantage to the U.S.

And, you know, on the second question, I think we still have more work to do with our allies to help us with the FONOPs. I don't think it's reached that sort of level of regularity that I think is what's necessary to really just make a firm, consistent statement that the world is just not going to sacrifice international norms and international law in terms of what innocent passage has been the norm for 70 years. That's something that is just so important that we get more countries to help participate and send that consistent, persistent message.

CROPSEY: Well, we have one minute left, and by coincidence, one question left. So let's see. Sir, here.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Intel analyst and a former diplomat. In my earlier life, I was an oceanographer. And we always had guys on the deck with a walkie-talkie, and there were no ship collisions. Seems like a no-brainer. The question: isn't the time for an upgrade on icebreakers, and do we really have to source it from the U.S.? Isn't there any way to get an icebreaker-competent nation like Finland to take the contract, or maybe to do the construction work here, under a Finnish contract?

COURTNEY: As you know, the Seapower Committee, we don’t really have the Department of Transportation or the Coast Guard directly under our purview. However, we have authorized over the last couple of years the legal framework for the Navy to work with the Coast Guard and actually help them with the shipbuilding program, because the size of these ships are really sort of just bigger, and outside the Coast Guard's sort of regular shipbuilding programs. And we've actually had a very good response from the Navy in terms of wanting to help with that.

I mean, your question is actually very timely because we just got word in the budget process – the appropriations process – that the Department of Transportation budget that's coming out of the House actually does not have any money for icebreaker construction. So I think there is going to be a bunch of us that are going to be offering an amendment. Hopefully it'll fare better than the submarine amendment in terms of trying to keep the momentum moving forward, because we've had some good preliminary steps in terms of design – getting that seeding into the process and moving forward. As far as the question of whether or not we could take advantage of Finland's very superior competence in this area, we've had visits from the Finnish government and their defense ministry and coast guard ministry to talk about that in our office. I don't think we're going to buy Coast Guard cutter – excuse me, icebreaker – and just plop it in the U.S. Coast Guard. However, it's been so long since we've done this in this country that there's clearly competencies and systems and help that I think it would be crazy for us not to take advantage of. And so I think there's going to be some collaboration at some level, but not the full boat.

CROPSEY: Congressman, thank you so much for joining us today.

COURTNEY: It's a pleasure.

CROPSEY: I hope that you'll come back, and we can continue the discussion.

COURTNEY: Happy to.

CROPSEY: And we'll be in touch with you and your staff. And for all of you who asked good questions and listened so patiently and well, thank you for joining us. And we look forward to seeing you at the next similar event.

(APPLAUSE)