‘I have been instructed to inform you,” an official told Vladimir Voinovich in 1980, “that the patience of the Soviet authorities and the people has come to an end.” The official, a district boss, loomed over Voinovich, who wrote that he imagined the next step would be execution on the spot. Instead he was stripped of citizenship and forced into exile near Munich for “defaming the motherland.”

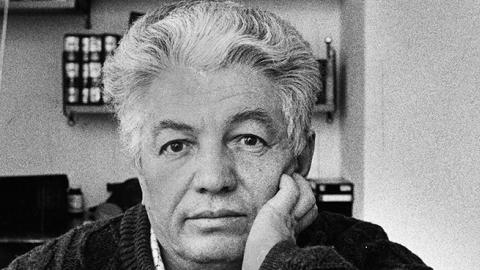

Voinovich, who died July 27 at 85, returned to the Soviet Union in 1990. Eventually he was hailed as Russia’s greatest living writer. But he never lost the qualities that wore out the Soviet regime’s patience. His singular gift was to see things as they are. In his most famous work, “The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin, ” he depicted the Soviet people, personified by a bumbling Red Army private, not as heroic builders of communism, but as innocents buffeted by forces they didn’t understand.

At an army lecture, the first question is: “Why is our army called a ‘people’s army’?” The answer: “Because it serves the people.” Next question: “Who do the armies of the capitalist countries serve?” “A clique of capitalists.”

Chonkin raises his hand and asks if it is true that Stalin had two wives. He is immediately assigned to guard a plane that has crashed near a collective farm where, disillusioned with politics, he spends his time talking to a horse. “If you say the wrong thing to a person you can get yourself in hot water,” he observes, “but no matter what you say to a horse, he’ll accept it.”

After the fall of communism, Voinovich was asked if it was still possible to write satire in Russia. He insisted it was. “The Soviet Union was a giant mental hospital,” he explained, “but it was an organized mental hospital. Now the inmates have been told that they can do whatever they want.”

In all his writing, Voinovich was a foe of the underlying totalitarian mentality. His essay “The Only Correct World View,” part of a 1985 collection, describes a woman who said she would have strangled the terrorists who killed Czar Alexander II in 1881. Voinovich said that in 1881 she would have been throwing bombs alongside her intended victim. “You don’t know yourself well enough,” he told her. “These days it’s fashionable to be a confirmed monarchist. But back then it was fashionable to throw bombs at the czar. And given your character, there’s no question you would have been with the bomb throwers.”

The tragedy of present-day Russia for Voinovich was that the transition from socialism to capitalism wasn’t accompanied by a change in people’s character. In his book “Moscow 2042,” published in 1986, he described a new Russian regime run by state security and based not on Marxism-Leninism but on the teachings of the Orthodox Church. Like Russia today, the regime tells its citizens they are surrounded by “three rings of hostility.” The first is the former Soviet republics; the second, the former Soviet satellites; the third, the West—the former “capitalist enemy.”

Voinovich never finished school and was rejected when he applied to a Moscow literary institute. But he had worked as a railway laborer and construction worker and knew the spirit of Russia firsthand. He predicted in the 1980s, while he was still in exile, that the Soviet Union would face radical change because the authorities were “doing stupid things.”

In recent years, he predicted the collapse of Vladimir Putin’s regime for the same reason. “All branches of power are working as one and approaching some sort of explosion,” he said in an interview with Radio Liberty in 2012. “That explosion will definitely come because it isn’t possible to upset such a large—and daily growing—number of people day after day.”

Voinovich was fully aware of the regime’s ability to hide reality. But he also believed that in the long run, lies can work only in a closed system. “A naked person only seems natural in a sauna,” he said. “When he goes out into the street, people will either laugh at him or stone him.”

Voinovich’s death deprived Russia of a powerful defender of the dignity of the individual. But as repression grows, his influence is likely to increase. Russian society is too developed for the regime that has been imposed on it. Voinovich’s insights, like his example, offer hope that it will not long endure.