Navigating GPS Vulnerabilities: Implications for US Economic and National Security

Commissioner, Federal Communications Commission

Senior Fellow

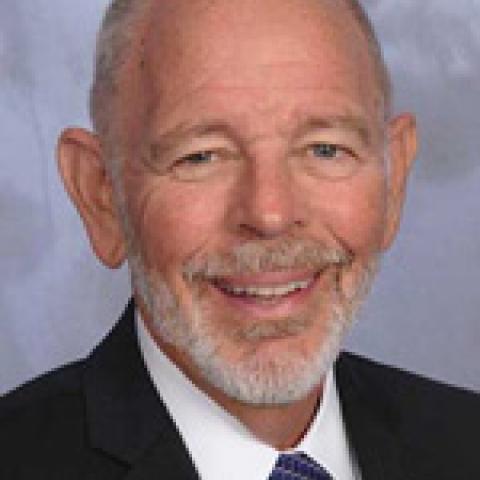

Robert McDowell is a senior fellow at Hudson Institute and former commissioner of the FCC.

President, Resilient Navigation Foundation and Member, National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Advisory Board (PNTAB), National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Ashley H. Priddy Centennial Professor in Engineering, University of Texas at Austin

Professor and TRC Endowed Chair in Intelligent Transportation Systems, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Ohio State University

Senior Director, Center on Cyber and Technology Innovation, Foundation for Defense of Democracies

Senior Fellow and Director, Center for the Economics of the Internet

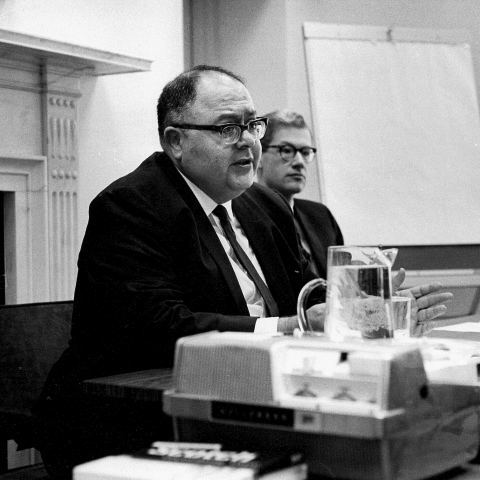

Harold Furchtgott-Roth, former commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission, is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.

Beyond merely guiding Americans to their destinations, the Global Positioning System is essential to the United States’ electricity grid, financial markets, and wireless networks. First responders rely on GPS to locate individuals in distress. Many US military systems rely on the position, navigation, and timing (PNT) functions of GPS, and systems similar to GPS have been central to new forms of warfare such as drones and precision guided munitions.

But current US GPS technology is 51 years old and grows increasingly fragile as new, more resilient American GPS satellites sit idle in warehouses. Hostile nations such as Iran and Russia frequently spoof GPS so that ships mistake their actual location. Airline pilots encounter GPS jamming in many parts of the world, especially near the Russia-Ukraine border. Perhaps worse, the US has no robust backup to GPS, which could prove catastrophic in a military conflict or a natural disaster.

To explain the challenges facing GPS and how Washington can solve them, Hudson will host an event with several leading authorities on the system.

Agenda

10:00 a.m. | Panel Discussion

- Robert M. McDowell, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

- Dana Goward, President, Resilient Navigation Foundation

- Todd Humphreys, Ashley H. Priddy Centennial Professor in Engineering, University of Texas at Austin

- Zak Kassas, Professor and TRC Endowed Chair in Intelligent Transportation Systems, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Ohio State University

- Rear Admiral Mark Montgomery, Senior Director, Center on Cyber and Technology Innovation, Foundation for Defense of Democracies

Moderator

- Harold Furchtgott-Roth, Senior Fellow and Director, Center for the Economics of the Internet, Hudson Institute

11:00 a.m. | Keynote Address

- Nathan Simington, Commissioner, Federal Communications Commission

Event Transcript

This transcription is automatically generated and edited lightly for accuracy. Please excuse any errors.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Hello, my name is Harold Furchtgott-Roth. I’m very happy to welcome you here to the Hudson Institute. Today we have a wonderful program about GPS, its current situation and weaknesses and potential future of GPS. We have a distinguished panel of experts who will tell us about GPS in a lot of different perspectives, and that will take up the first little over an hour. Each of our experts will speak for about 10 minutes. Then we’ll have a little bit of an open session after they speak. Then we’re very pleased to have with us Commissioner Nathan Simington of the Federal Communications Commission, who will give us a keynote address at the end, and then we’ll have a little bit of time for discussion after that as well. To keep on a tight timeline, I’m not going to give lengthy bios. They’re available online. These are very well-known experts, and so you won’t have any trouble finding more information about them. Our first speaker is Dana Goward, who will tell us a bit about GPS. And Dana, you can either sit here or you can speak from the podium.

Dana Goward:

Thank you very much and it’s a pleasure to be here. So the first slide, if you would please. So I’m privileged to be the president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, and we are actually a public benefit charity and we chose that form of organization because the IRS allows us to have commercial members that support our mission, but we are prohibited from giving any direct benefit or support to them and their business interests. So that allows us to give unbiased advice and consult to the public and government leaders as much as we possibly can. Let me start out by saying that GPS is a great system. It’s been America’s gift to the world. We should be very, very proud of it, and we should use it whenever and wherever we can trust it. The challenge is the way that we use it and how many people abuse it.

So you have heard that the GPS. . . Next slide, please. Everything in technology depends upon GPS, and that’s absolutely the case, but that’s not really the problem as much as the problem is that everything depends upon everything else in our society. Electrical grid, it takes inputs from GPS. It also powers IT networks. IT networks power the electrical grid and so on and so forth. So when you have a problem in an underlying silent utility like GPS, which provides us the position navigation timing services that we need to feed all these technologies, you have the possibility, the probability that these problems will cascade throughout society and be a significant challenge if we ever have a substantial disruption. In fact, so significant that a current director at the National Security Council has called GPS a single point of failure for America, a pretty serious statement that she’s not the only one that has made that upon occasion. In fact, the father of GPS, Dr. Brad Parkinson from Stanford, who was the first chief architect, has made that statement as well.

So why is this a problem? Next slide, if you would. Well, GPS is vulnerable in two ways. One is that it’s a very, very, very, very weak signal. In fact, the stars twinkling and the sun sparkling make more radio noise than a GPS satellite does. And that means that any kind of radio frequency noise on that frequency or in that spectrum can deny prevent receivers from receiving GPS signals. And the second is that this was America’s gift to the world. So we made the specifications of the signals public in order to encourage adoption, and that worked just incredibly well. It has been adopted for all kinds of things by smart engineers who had this highly precise free signal that they could access and incorporate it into innumerable applications and systems and that is done. So you have a weak signal that’s easily imitated and is a single point of failure. So that makes it a very, very desirable target for people who would do us ill.

As you can see here, and there are wide variety of threats from the very small low-end threats that can just deny GPS signals within 100 yard radius to global threats, such as the purported Russian nuclear weapon in space and even the sun with coronal mass ejections having the potential to disrupt GPS signals. In fact, we saw a little bit of that earlier this year when spring planting was disrupted just a bit because of interference with precise GPS signals on the part of the sun. So broad spectrum of threats.

Next slide if you would. But there’s also the potential for accidental disruption. And we haven’t looked at this in the United States, but the European Union looked at it quite a few years ago, and they found hundreds of thousands of signals that could potentially interrupt GPS or we say GNSS, global navigation satellite signals because Europe has Galileo and Russia has GLONASS and China has BeiDou, they’re all GPS-like systems, and they’re all in the same frequency band. So they found hundreds of thousands of potentially interrupting signals, only about 10 percent of which they deemed malicious, but they were able to divide those into 300 interference families or 300 types of devices that were manufactured specifically to interfere with these kinds of signals. So lots of accidental disruption as well, next slide, which we should not take lightly as saying, “Oh, it’s just local and sometimes transient.” If you noticed in the previous slides, some of those signals were on air for a long time.

And mistaken signals can have a really bad impact as well. We had an instance in Sun Valley, Idaho in 2019 where a passenger aircraft was flying through the haze following its GPS approach to the runway and sun of a gun 100 miles away, alert radar controller said, “You are headed straight for the mountain and you’re going to impact. Turn right immediately.” Averted a tragedy at the very last minute. So all of these things are very important in terms of the safety of life and property and the normal conduct of life as we know it in our technological civilization.

Next slide, if you would please. And of course, we are very much concerned with intentional disruption. Russia has been at the forefront and pioneered development of this ever since the end of the last century when they first started advertising GPS jammers. You see here, an announcement in the Moscow Times that as a result of the fact that people in Moscow found they couldn’t find a ride to the airport if they were anywhere near the Kremlin because their GPS devices would tell them, “You’re already at the airport.” This started out as a way to protect VIPs from drones because most drones, if they think they’re at an airport, they will either fly away or land. So if you create an electronic field around the Kremlin that lets it look like it’s at an airport, the drones will go away.

But this quickly progressed and went through the dark internet into all kinds of bad actors to being capability to make GPS receivers of all kinds and for all reasons think that they were someplace else, things like hiding Russian oil tankers so they can avoid sanctions, in Mexico, directing trucks that are carrying valuable cargo to areas where they can be easily pirated. And next slide, if you would. And as Russia has found out, it’s a great way to make low level warfare on your adversaries without firing a shot.

So this is a picture of GPS interference in the Baltic at the end of December. As you can tell, it didn’t start out quite this bad, but it started out on the 15th of December when the Polish activated an American aegis anti-missile system on their border with Kaliningrad. As soon as that was activated, jamming and spoofing began in that area. And then as they were able to move more resources into Kaliningrad to increase the jamming and spoofing, it spread throughout the Baltic and throughout that entire part of Europe. So great way to put the knife in your adversary, again, without firing a shot.

Next slide, if you would. So spoofing has progressed quite a bit, and this is a picture from the early days of spoofing. We saw a number of interesting things, had something to do with the software and the hardware. We’re not sure why. So some of the earliest spoofing that we saw in China seems to have been related to Iranian oil imports and involved circle spoofing where the fakes position went around in a circle counterclockwise at about 30 knots, I think was the finding. Not sure how that ever happened or why, but we don’t see a whole of that now anymore. It’s just displacing an aircraft or a ship from some place where it is to some place where it isn’t so it can’t be discovered.

Next slide. After we saw circle spoofing, we saw circle spoofing moving way across the earth. And again, we don’t know why they all got transported to Point Reyes, California, but you can see that’s pretty dramatic tracks and not at all possible for vessels of any kind to do that. Next slide, if you would. Again, spoofing whether it’s intentional or unintentional is very dangerous. Here’s more recent example of a passenger airliner that almost flew into Iranian airspace as a result of all the jamming and spoofing that’s going on over in the Mideast and near the Ukraine. One more slide. And spoofing is so popular, so prevalent that there’s even a website now that you can go to and see all of the aircraft that are being spoofed. You can even drill down to the individual aircraft, get a picture of them, of what their flight plan’s supposed to be, where they are, where they were spoofed to and so forth.

Next slide, if you would. And it’s not just the Mideast where there’s open conflict or in the Ukraine, certainly this is happening on a regular basis in the Baltic way too far away from Moscow or any place that they need to defend from drones. You’ll also see it in Kashmir and in Myanmar. Pretty much any place there’s going to be armed conflict, any rational reasonably well-equipped military is going to employ electronic warfare and begin interfering with GPS.

Next slide, if you would. And it’s only going to get worse. This is a report, if you’re interested, that was recently issued by a group of aviation experts from around the globe, and they postulate that it’s going to get worse, and I think everyone has to agree. Why is that? Well, the trends are in that direction and there are no disincentives to doing it and a lot of incentives to doing it. Very difficult to counter this to make people stop doing it unless you’re in an armed conflict and you’re able to send missiles at the transmitters.

Next slide. Finally, this whole position navigation and timing thing is clearly an issue in great power competition. This is a chart that the president’s National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Advisory Board provided this summer to the Deputy Secretaries of Defense and Transportation. And it shows you that unlike the United States where we rely almost exclusively on GPS, China has not only advanced their satellite navigation system, but they have a host of terrestrial systems to back up and provide that PNT service when and if signals from space are not available.

Next slide, if you would. And in fact, they have the one yellow block that that was on that slide for China has recently been completed. So they are sitting in a very good position and conceivably could interfere with GPS signals at the same time, us being able to do the same kind of thing to them would be problematic because it would have virtually no impact on their military or their civilian population.

Next slide, if you would, which is the last one I believe. And even more recently, we have found that it is quite likely that both China and Russia have the ability to interfere with GPS signals from space, GPS and all kinds of other navigation signals from space. The BeiDou constellation is almost certainly able to transmit signals and imitate Europe’s, Galileo and America’s GPS system, so spoof from space or deny signals from space, which would eliminate a lot of the countermeasures that folks count on to be able to survive that kind of attack. And Russia has almost certainly deployed a long-planned nuclear-powered electronic warfare device in space that is able to not only impact GPS on the ground and other signals, but a wide variety of communications and other links. So very much an issue in great power competition. The United States is incredibly vulnerable. We are way behind Russia in terms of terrestrial and certainly well behind China. How do we get there? What can we do about it? Well, I have some very definite thoughts about that and I look forward to the discussion.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Thank you very much. Our next speaker is Professor Todd Humphreys from the University of Texas, and he’ll be speaking to us via Zoom. Professor Humphreys.

Todd Humphreys:

Dana, thanks for the great warmup and I appreciate Harold inviting me to this and the Hudson Institute for hosting it. Also, I want to point out that a lot of the research that I’ll be presenting on is supported by the Department of Transportation under the CARMEN+ UTC. It’s actually led by Zak Kassas, who’s right there with you today. So I’ll get right to the point. Just as Dana said, this last year has seen the most intense attacks against GPS and GNSS, in general, in history.

We’ve already seen these charts, the red spots indicating where GPS interference is prevalent. And with more recent times, this is moving into Eastern Europe and expanding across different areas, not just in conflict regions. And as Dana mentioned, last year around this time, September 2023, it was the first clear case of spoofing of a commercial aircraft. This aircraft was almost duped into flying in restricted airspace over Iran, and even its downstream inertial reference system got corrupted by the GPS spoofing because of the dependencies there are in the avionics systems on GPS.

Just a couple of weeks ago, this was front page news in the Wall Street Journal, that fake GPS signals are causing trouble for airlines and pilots. It doesn’t stop with the terrestrial sphere in low earth orbit. You can see here the orbit paths of a very large low earth orbit constellation. The red and blue dots indicate GPS is available to the spacecraft in those areas, and a big hole over the Ukraine region indicates that GPS was denied. It wasn’t a problem for this constellation because they’ve got stable orbits and stable clocks. But imagine if this were something seen, say, in a dozen places around the globe. Now that constellation has a hard time synchronizing and doing station maintenance and avoiding collisions.

And this extends to other future constellations. This is the AST SpaceMobile, very large array of antennas that is meant to communicate directly with handsets on the earth, but the only way they can coordinate the beams across all of these phased arrays is to use GPS to ensure that the phased array is flat enough. And so we’re building dependency even into future systems on GPS, which is, as we know, quite fragile. And it’s even being built into standard cell phone protocols. The way that your phone will talk to satellites going forward, according to the 3GPP standard body, is going to assume that your phone can obtain a GPS fix in order to link to these satellites. So think about a disaster situation where the only communications is over satellite, and now your phone is critically dependent on having GPS.

There’s a place you go to complain about GNSS interference, and the relevant authorities went there. This was the ITU World Radio Conference back in December. They went to emphasize to try to pass a resolution that would emphasize the protected status of the GNSS L1 and L5 bands. But interestingly, it wasn’t possible to get agreement on this resolution without introduction of a caveat, which I think ironically weakens the protection of these bands even more than they were before. Dana talked about that this is only going to go on, but I’m trying to explain here why, the why this is going to be around for a while.

If you look at the fine print of the resolution that was passed last December, you see that they introduced a caveat saying without prejudice to the right of administrations to deny access to the RNSS for security or defense purposes. So what does this mean? This explicit caveat means that state-sponsored radio interference is here to stay because any country claiming a defensive purpose can jam or spoof signals with impunity, even if the effects are felt far beyond their borders. In other words, what Russia is doing, what Israel is doing, what other countries are doing in interfering with GPS is no longer clearly illegal.

Now, there are a couple of bright points on the horizon. One is that resilience is getting cheaper. And I like to point out that two technologies, namely software defined radios and phased arrays offer hope for a more resilient PNT. And it’s not because they’re new, it’s because they’re newly cheap. We’ve made them cheaper than ever before. This device is a remarkable bit of kit from Xilinx. It basically is more powerful than the best radio that I was able to get for my laboratory here for $150,000 when I began being a professor here. Now you can buy this for what I call 40 DB dollars or $10,000. It’s got enormous flexibility across time and frequency and would enable GNSS receivers to hop around in time and frequency, thereby looking opportunistically for signals they could pull PNT from.

Also, phased arrays have gotten remarkably cheap recently. When Starlink first introduced their service back in 2019, the phased array was about $3,000. It’s now come down to about $300 their cost. This offers extraordinary spatial and polarization agility, not something that we can leverage in the L-band so easily because phased arrays in the L-band are large and cumbersome. But as we move up to higher frequencies in GNSS, we can make more compact phased arrays, and this offers much better spatial agility. So a recommendation that I would have for future GNSS that we should make use of the already allocated 20 megahertz in the 5 gigahertz band, what’s called the C-band, and higher frequency, such as the K-band to promote use of phased arrays on GNSS receivers. So if you’re talking lower frequencies, longer wavelengths, phased arrays are not so practical, but at higher frequencies, smaller wavelengths, they become quite practical. So I would make this recommendation.

Another point to be made is that interference, GNSS interference is quite conspicuous. You remember the kinds of activities we’re seeing in the Eastern Mediterranean even before the war in Ukraine. We installed a GNSS software defined receiver on the International Space Station some years ago, and we used this to try to figure out where those signals were coming from that were causing such trouble in the Eastern Mediterranean. Turns out it was a Russian spoofer jammer operating in Syria. We were able to locate it within a couple of hundred kilometers just using the data from the International Space Station’s specialized receiver that we operate. Later on, we supersized this by bringing in a commercial partner, Spire, and by doing what’s called dual satellite capture, which allows us to capture signals even though we might not be able to pull a carrier signal from them. By focusing our attention on the Near East, we came up with dozens of different interference spots, and my students had fun zooming in on each of these to find out what might be there. This is typical, you see near our lowest cost point, you see a military installation.

You remember this case of spoofing of an aircraft near Iran. We were able to use the signals from a low earth orbit constellation that had also been spoofed to identify and locate the likely source of the spoofing causing trouble for this aircraft and for many others like it. And it was found on the eastern periphery of Tehran in Iran. Also, all of the spoofing that’s been going on in the Eastern Mediterranean over the last about nine months or so, we’ve been able to locate one of the most important sources of that spoofing to an air base in Israel, so the Israelis themselves are engaging in this spoofing. Again, I want to emphasize that it’s no longer clearly illegal when you have a good defensive reason to engage in the spoofing.

So I’d like to set a recommendation to exploit these kinds of LEO eyes on the ground. I’d say that we should make a national goal to be able to locate a one watt source to within 10 meters within 10 minutes. And I think this is entirely dual using LEO assets that the US have or will have going forward. What about backups? Dana mentioned some of these. I just want to mention two. Alternative sources of PNT, they could be plentiful. eLoran is a good example. He mentioned that China has just completed an eLoran deployment across their country. I also think. . .

Todd Humphreys:

. . .An either end deployment across their country. I also think LEO mega constellations are highly promising, and in fact, we and the Radio Navigation Laboratory here at the University of Texas have been asked to partner with Amazon’s Project Kuiper to build in a secondary PNT service fused with their communications mission. So this is going to be a constellation of thousands and thousands of communication satellites, but they’re going to build in a purpose-built PNT service for their users for global access, and I think that’s tremendous. It’s going to offer a backup to GPS and keep some of the pressure off of GPS. But it won’t be available for some years to come. Okay. I’ll stop there and look forward to the panel discussion.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Thank you very much, Todd. Our next speaker is Professor Zak Kassas from Ohio State.

Speaker 1:

Congrats on the big win.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

We’ve got a college football playoff, Texas and Ohio State. Magic works.

Zak Kassas:

Okay, so good morning everyone. Thank you, Harold, so much for the invitation. It’s an honor to be with an esteemed group of colleagues and panelists and pioneers in the field, such as Dana and Todd Humphreys, who I know very, very well.

What I’m going to give you today, the message that I want you to leave with is a message of hope, which is basically why I say I’m not afraid of the GPS jammer. So this is work that have been done in my research lab at the Ohio State University, and prior to that at the University of California, funded by Department of Transportation, the Office of Naval Research and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, International Science Foundation.

But to motivate the state of the world that we live in today, not too long from now, we will be ordering lunch maybe through, maybe a taco delivery drone. I’m not endorsing Taco Bell in any shape or form. But let’s see where we are today and are we ready for this future that we are all dreaming about and everyone is excited about?

So as the drone takes off, it’s trying to deliver you the taco. It relies on GPS to navigate. There is no human in the loop driving it, so to speak. Now, imagine GPS is lost for one reason or another, jammed, spoofed or otherwise. The drone flies on what is known as the inertial navigation system, which isn’t enough for the drone to know where it is. The drone really is lost at this point over this crowded city, flying aimlessly. It happens to fly over this power substation, tangles on the power lines and falls in. So without GPS, we can’t even fly drones safely or reliably, and they will start falling from the skies like dead birds.

So if you think that this is sci-fi, we are far away from this future, I will tell you, that’s not the case. In fact, it happened to us. Ironically, we were not delivering a taco. We were actually testing a 5G backup navigation system on our drone. This is our drone here. If it had fallen behind this fence, we would have hit the high-voltage bus in the Johanna substation in Orange County, cutting power to hundreds of thousands of customers, and you would have heard about us in the news, not in a good way. In fact, as my students were looking for the drone when it’s lost, they found the security guard. They said, “Yeah, yeah, I took a video of your drone,” and this is showing it flying aimlessly.

So what this tells us, we need improved fall detection, isolation and recovery. We need a backup navigation system, as Dana and Todd mentioned, and we need to secure our critical infrastructure. I’ll not go through this. Dana and Todd did a great job telling us about what is really going on. It’s not a secret anymore that jamming and spoofing are scary, especially for aviation because it’s a safety of life application.

And this is really not new in the aviation world. In fact, in 2019, the international Civil Aviation Organization had a technical letter for an urgent need to address harmful interference to GNSS. They followed that in 2020 by another memorandum. The Department of Transportation Volpe report in 2021 looked at complementary PNT and backup GPS technologies, and NIST had their Foundation of PNT Study for cybersecurity framework for resilient PNT and responsible use of PNT. 2022, the ITU issued a circular letter on the prevention of harmful interference to GPS or to radio navigation bands. And then just this year, the FAA issued a warning or a safety alert for operators on recognizing and mitigating GPS interference and disruption.

And the bubble burst in 2024. As Todd mentioned, it has been a very busy year, in a bad way, for aviation. You can see here news stories and mainstream media, it’s really happening all around the world and impacting aviation, which as I said, should be a concern for all of us.

So the message I would like to leave you with, if you know where this is from, it’s from the X-Files. The truth is out there. So the message that we are trying to deliver here is that we have infrastructure that is built. We have spectrum that is licensed. Why don’t we reuse it? So those signals in the research community are called signals of opportunity. They could be terrestrial, AM/FM, digital television, cellular, or they could be non-terrestrial. There is of course a lot of excitement about LEO, or Low Earth Orbit mega constellation. So that’s what we’ve been studying over the past few years. But what I want you to see is how well can we do repurposing the infrastructure that we have to navigate, and can we achieve what we get with GPS, which is a dedicated system for navigation?

So this is not a particularly new work. In fact, this is from 2019, and so far we do hold the record, hence this gold medal here, for the most accurate navigation of a drone by listening to cellular 4G LTE signals. What you see here is what you could get with GPS in blue, versus in red, what we are able to achieve listening to cellular towers in the environment, sub-meter level accuracy.

Then we got challenged by our friends in the Air Force saying, “Can you do this on a high-altitude aircraft?” And we said, “Challenge accepted.” This is the badge that the pilots wore as they flew the campaign that they called SNIFFER, which stands for Signals of Opportunity for Navigation In Frequency-Forbidden EnviRonments. I used to be in UC Irvine and that ugly thing there is their mascot, which is an anteater. Now I’m in Ohio State, so we have a Buckeye. So I don’t know which one is better.

But what we had studied in my lab is designing these high-sensitivity receiver. We are all guilty of it. You turn on your cell phone. As you go higher and higher, you cannot communicate back. It tells you there is no signal. Well, the thing is, there is a signal, it’s just so faint. And it’s enough though for us to listen to it. It may not be enough for your phone to talk back, but if you want to navigate, you want to do it passively, you don’t care to talk back. You can listen to the signal and use it and navigate the aircraft. I warn you not to blink, because this is how many signals we were able to see after we improved our design. More than 100 cell towers were hearable up to altitudes of 23,000 feet above ground, from towers more than a hundred miles away.

This work was recently featured in IEEE Spectrum, inside GNSS, among other media outlets. Let me show a quick video of this flight campaign that took place in southern California. They call her Ms. Mabel. That’s the C-12 aircraft that the pilots flew, basically to see, can we fly this aircraft? They flew it over several also regions in Southern California, suburban, urban, and even over the Mojave Desert, trying to basically exercise different maneuvers and different population densities. So let me zoom in and show you how accurately we can navigate the aircraft with no GPS. So that’s in green is what the aircraft told us. They said, this is how we flew. Can you tell us how we flew? And it told them in red, this is how you were flying. So it is within a meter accuracy.

So we heard a lot about jamming. So another natural question would be, what if someone intentionally is jamming GPS? We know that the cellular infrastructure depends on timing from GPS satellite. So can we still use those signals if GPS is jammed? So to answer this question, we went to the desert during an exercise called NAFEST that Edwards Air Force Base was conducting. They basically jammed GPS and all kinds of experiments start taking place. Our goal was to see, can we navigate a ground vehicle when GPS is intentionally jammed? This work got a prestigious award called the Harry Rowe Mimno Award from the IEEE Aerospace Electronic System Society for the most impactful work over that year.

So let me show you what we had done. So it was Edwards Air Force Base during NAFEST. They started jamming around midnight up until about 4:00 or 5:00 AM. So this is us driving in the middle of nowhere in the desert, heading, really, to hell, as they say. We know we will be lost. Let’s see how well we can do.

So that’s the vehicle equipped with our software and hardware. That’s where the jamming was taking place. And we said, okay, we’re going to use these cellular towers to navigate the aircraft and see, can we do something useful when they start firing up these jammers, which are enough basically to knock down GPS throughout the whole area. So let me zoom in.

So, so far so good. We started driving towards jamming before they fired up the jammers. And you see what we are able to estimate from cell towers versus GPS is pretty close. That’s when they started the jamming exercise. You see here, that’s what my phone was showing. This blue halo kept increasing to a radius more than six kilometers. It started jumping up and down like it’s possessed by the devil. Basically, it doesn’t know where it is. In red, you see what the GPS system on the vehicle was telling us. It just kept drifting off and off and didn’t know. Whereas with our system, we were able to navigate about five kilometers to about a couple meters in accuracy.

So, Todd alluded to LEO mega constellations. We live in exciting times, and there is a new space race, they call it. So historically I like to think of GNSS, Global Navigation Satellite Systems, whether they are the American system GPS, the Russian GLONASS, the European Galileo or the Chinese Beidou, they monopolize truth. They monopolize position, navigation and timing. However, GNSS satellites are making new friends in LEO. These are the Starlinks of the world, OneWeb, Iridium, Orbcomm, Kuiper, and so on and so forth.

So the idea is, can we use this canvas of satellites that will blanket earth for PNT? And that’s what we’ve been studying. We started looking at this several years ago. We were the first to crack the Starlink constellation and turn it into a GPS-like constellation. We didn’t work with SpaceX. They were surprised like everyone else when we released it to the world. Was featured in Science. Then we went after several other constellations.

Essentially, we cracked five constellations. Simply listening to their signal, we were able to know where we are. So two OneWeb satellites, one Iridium, one NOAA, four Starlinks and one ORBCOM. As I mentioned, I used to be in UC Irvine, so I told my students, “Let’s imagine we are in UC Irvine. That’s what the challenge would be. By listening to these satellites, can you tell me where I am?” While we were at the rooftop of one of the buildings in Ohio State, and we managed to localize ourselves within five meters, which is more or less what you get with GPS.

But of course, we want to see how can we do this on a moving vehicle, so that was the next set of work. So this is the first and most accurate demonstration with multi-constellation LEO satellites in what they call non-cooperative fashion. So those satellites are not sending a signal to navigate with. We are hitchhiking on the signal. We are not building new infrastructure. We are not licensing new spectrum. We are reusing what we have. So a cheap analogy would be, you don’t throw in more taxis in a city if you want to solve the issue of transportation, you just start having ride shares like Uber and Lyft and so forth.

So what you see here, cutting GPS in red is where the vehicle starts thinking where it is. It’s on the other side of the freeway and then it goes off of the freeway altogether. Whereas in green, look how accurate we are able to estimate how the vehicle is traveling. So with that, thank you so much, Harold, and a big thank you for the sponsors of my lab, the Office of Naval Research, the Air Force, Department of Transportation, National Science Foundation, and the Aerospace Corporation. Thank you.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Now my Hudson colleague, Commissioner McDowell.

Robert M. McDowell:

Really well done. Thank you, Commissioner Furchtgott-Roth, for putting this together, my Hudson colleague. Delighted to see so much attendance here today, and for the folks watching online, this is a very important sleeper issue. One of the most frustrating things about it is that it has not gotten enough attention in Congress. We are starting to see more press coverage of these issues, as you saw earlier, mainly related to jamming. I’m batting somewhat clean up, so this is great. Great introductions and overviews. I’m going to drill down and this is going to be a little bit hodgepodge, so I apologize. Some notes that I’ve written along the way.

So first of all, it’s important to understand that US GPS, that system is about 51 years old. It was invented in El Segundo, California, where my brother was mayor at one point. Later. Had nothing to do with GPS. But small world. And so Space System Command is there. You had Howard Hughes and Hughes Satellite and LA Air Force Base and other reasons why, that all happened in El Segundo, right by LAX Airport.

But our GPS system in the US has not evolved from 51 years ago. Congress, a few years ago, however, did see the need to modernize it, thankfully, and allocated or appropriated money to do so. So 17 of 24 L5s. . . We’ll talk about L1 and L5 here in a minute. GNSS satellites have been launched and are in orbit, but inexplicably, without oversight from Congress, four remain in storage in Colorado.

Now, these have cost you, the American taxpayer, about a half billion dollars each, and that’s $2 billion, if my math is okay, sitting there stranded in Colorado, plus billions more up in the sky, of 17 satellites, which are sitting there useless, somewhat useless. At the same time, the operating system, we call it OCX, is still under development and years behind schedule. Meanwhile, there seems to be no oversight of any of this in Congress, and this is a very frustrating matter.

Along the way, if I can go to the. . . There we go, right up there. Perfect. You anticipated it. Thank you. Along the way, we’ve had our friends in Europe, but also the Chinese, launch full complements of L5 GNSS satellites. So what we’re seeing here is sort of a breakdown of who has what and how many. So this is L1 right here. How many satellites do you have in L1. So the L1 band, for those of us in FCC land, we’ve often just referred to it as the L-band. It’s a crowded band. It’s where GPS is. It’s where some of those companies are that were on that slide deck a few minutes ago.

And by the way, I should have said at the outset, I am a partner. I’m the chair of Cooley’s global communications practice. I’m not speaking on behalf of any client today, although a few have been mentioned, but I’m not speaking on their behalf.

So the L1 band is more crowded and the signals there are fainter. You can’t have as high power levels as you can in L5. L5 is a sort of cleaner band and you can have much higher power levels there. And I believe the professors who actually are far smarter than I am answer questions regarding that. But that’s an important point to know. So L1 is great, but it is more vulnerable to everything you’ve been hearing about.

So when you jump to the next slide, we see that our friends in China have 27 L5 satellites up. We only have 17, which are not operable. And we have Galileo, Europe’s version of L5 GNSS, with 25. Meanwhile, GPS was invented in the United States. We are now way behind, a decade, maybe 15 years behind Europe and China vis-a-vis the next-gen GPS.

That’s really important to consider, especially, there’s national security, and that’s at least half of this discussion today is regarding national security, but also economic security. The NIST, which was cited earlier by the professor, has estimated that GPS contributed about $1.4 trillion to the US economy. I’m thinking it’s higher. I would love to know the metrics of that estimate. But when you figure that GPS underpins everything that was just described to you, the telecom infrastructure, everything, transportation, aviation, the stock markets depend on the position navigation and timing, mainly the timing of GPS, et cetera. So that’s really important to understand as we go forward.

So another part of the hodgepodge is L1 GPS is so vulnerable, and I will let, again, the people smarter than I confirm or deny this. You could have a handful of maybe large suitcase-sized jammers in lower Manhattan, which would cause tremendous havoc. You saw the havoc in the demos earlier, but tremendous havoc to the financial markets, let’s say. And don’t think that our adversaries aren’t thinking and planning this, and don’t think that China’s not planning things like this if they want to mess with Taiwan or other places. So keep that in mind.

So going forward, I think what you’re hearing today, and hopefully it’ll be much less than the 10 minutes I was allotted, is an all-of-the-above solution. So we’re next-gen L5 GNSS, let’s complete the US constellation and unstrand that stranded taxpayer capital, but also help us have more resilient next-gen GPS. That would be helpful.

But also, there are a lot of ideas for terrestrial backups. So whether it’s pinging off of cell towers, or whether it’s some startups out there that are looking at the ground as if it’s sort of like facial recognition software, you can figure out where you are based on the terrain. Over the ocean, that doesn’t really help you. Over the ocean, cell towers and looking at terrain doesn’t help you at all, so you need space-based. And you have multiple companies now, if you have a lot of satellites up there listening and broadcasting RF energy, you’re going to be able to triangulate off of those and have a lot of redundancy.

And I’ll sort of close by saying, within the Pentagon, and perhaps this has contributed to Congress’s lack of oversight, within the Pentagon, there are differing voices about what to do here. Some have very strong opinions one way or the other. Many folks sort of gravitate over there, it seems like, to a particular corner, and I know we’re going to hear from Adam Montgomery in a minute. Maybe he can help illuminate this. Particular corner, particular idea, and that seems to be the voice of the moment coming out of whatever office of the Pentagon.

Part of their thinking, or the thinking of some over there, is that in a hot war with China or whoever, one of the first things that happens is we’re going to take out each other’s satellites. So why bother finishing the L5 GNSS constellation? Well, first of all, if we’re in that kind of hot war with China, we got bigger problems. We have huge problems, right? In the meantime, you hope that doesn’t happen, but you finish the job that Congress told you to finish, and the Pentagon hasn’t done it, and why? And Congress hasn’t done its job by not overseeing this.

So I would love for more policymakers to be like Commissioner Simington, who we’ll hear from soon. He’s really the only federal policymaker who’s been very clear on this, and I want to congratulate him. He’s not here for to hear me say that, but he’ll be back in a minute. And we need more like him who can perceive this idea and carry it forth.

All right, so without further ado, after my hodgepodge, should I just introduce Admiral Montgomery?

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Please.

Robert M. McDowell:

Admiral Mark Montgomery.

Mark Montgomery:

All right, so I’m batting fifth, here. I guess I’m the Giancarlo Stanton of this group, which did not do well for him. First, thanks, Harold, thanks, Hudson, for putting this together.

We’ve heard a lot. There’s some, they weren’t breathless accounts today, but if you read the press, it’s kind of breathless accounts about jamming causing poor performance of US munitions. I spent the last couple of weeks in Ukraine. That’s true. There’s no doubt that our lower end munitions are performing poorly in a high-jamming environment.

Spoofing is having an impact. I was in Israel recently. Whole time I was in the north, I was in Beirut. The whole time I was in the south, I was in Cairo, according to my GPS system. It’s pretty obvious that it’s being heavily spoofed, being heavily spoofed. . .

Mark Montgomery:

GPS system. It’s pretty obvious that it’s being heavily spoofed in Ukraine, being heavily spoofed in the Baltics. The sad thing is this was absolutely predictable. This is not a shock. This is just like munitions, which the Department of Defense took a 25-year hiatus on, and oh my God, on February 22nd, 2022, we found out that all our munitions for fighting against Russia, for fighting against Iran, for fighting against China, were at 25 percent of need. And this was an investment decision made by the United States. We did this same conscious decision across 20 years to not prioritize the GPS mission, the electronic warfare mission in general in the Department of Defense. So whenever a Department of Defense person claims, “Things have changed.” Things have not changed. You’ve sucked for 20 years. What changed was you got caught. You got caught that the adversary is trying to use it.

And if you don’t think the adversary’s number one lesson from all this is fire ballistic missiles at us and jam our shit, you’re not paying attention. And until very recently, the military just viewed this as a nuisance. “Yeah, we’ve got our M-code, we’ll figure our way out of it and we’re okay.” And the military is extremely selfish inside the national security decision making process. They want to fix their thing. If you happen to be breaking their thing, they want you to fix their thing, and they don’t want you to hold them to any account for their stuff. If you’re supposed to provide support to them, DOD is afraid, and this is a legitimate concern, that the minute they get pinned with something, they get the bill for it because they are daddy war bucks of the federal government with nearly a trillion dollars. But they absolutely took a we’ll-take-care-of-ourselves approach with an M-code driven. . . M-code is an encrypted system that performs better, even on the L1 frequencies, it performs significantly better in a jamming environment.

Ironically though, they didn’t even do that well, and they’re behind on M-code. So now, as was mentioned, some of the decision makers are aggregating behind. “We got to get our act together in M-code.” Probably true, but there’s real flaws in this logic. M-code, it’s in systems mostly, aircraft, planes, some high end munitions. It’s not in a 155 round, or a GMLRS, or a small munition because the M-code is not a small product like a little L1 or L5 antenna. So it’s generally in systems, not munitions, and they’ve been slow as hell to get it into systems. It isn’t like the services have kicked ass at this, they’ve sucked. On top of it, we don’t share it with too many of our allies and we don’t share it with any of our partners. So M-code’s not a good solution if you want to fight with allies and partners, and all I hear from the United States is, “We’re the country that fights with allies and partners.” In which case your GPS policies are out of sync with your general strategic deterrence.

Most concerning, though, is the one that was just brought up, which is about private sectors. It is about the private sector, completely ignored. And let’s be clear, aviation ports and rails are what’s called military mobility. The number one demand signal on those in a crisis is the military. So the military will even kick itself in the junk. In other words, when it says we’re not going to care about the private sector, they’re not caring about military mobility. And I’ll tell you, the most of all the things we mentioned, it’s a hard contest between them, but I’ll tell you, ports need that PNT signal for almost anything that’s happening in the port. We’ve heard a lot about the cranes recently, but it’s the gantries, it’s the rail system, it’s the gates, they all run off a PNT timing signal. And the locations as well. If it’s not functioning properly, our military equipment, supplies, personnel are not getting to the front.

This is true at 19 strategic sea lift ports, 60 strategic air lift ports, everything I’m mentioning is not owned by the government, it’s owned by the private sector, operated by the private sector, and six rail systems. Then on top of it, you do have energy, precision agriculture, pipelines, water, all using PNT signals. And if they don’t work, eventually the rail, port, and aviation systems don’t work, so we’ll just generously say the private sector needs to work. And there’s no M-code plan for the private sector. There needs to be an alternative plan, and it needs to be able to survive better than a jammable L1 signal. And you’re absolutely right, on L1, reasonably, I could jam a few block area around here with something the size of that chair. If I want to do it with the L5 signal, it’d be something the size of this room.

And the Chinese, or our adversary, Russians, non-state actors, can get suitcases into our country. I’m not quite sure yet they can get 18 wheelers in and just position them around, do that kind of jamming. So I think we know there’s a good frequency available. Look, I’m for fixing M-code. I’m not opposed to that, but for the Department of Defense to say that’s what we’ll do first and then we’ll think about everything else is bullshit. It’s not taking care of national security or economic productivity. And we need to get M-code to allies and partners, which is not on the priority list. So look, we do have a good signal. Unbelievably, we did think of this problem in the 1990s and we did actually authorize solutions in the 2000s, and here we are in the 2020s nowhere near ready.

I think there’s the GPS IIFoxtrot and GPS III satellites. They all have an improved L1, which is nice, a civilian L2, which is nice, and most importantly, an L5 safety of flight signal. The IIFs, there’s 12 built, 12 launched, one of them screwed up. We’re now we’re at 11 up in the constellation. On the GPS III, there was 10 built, six launched, six operational. So we have about 17 operational. One or two more, we could have a reasonably healthy circuit up there. Not a safety of flight circuit. Here comes the next problem, Department of Defense ad Department of Transportation can’t come to some kind of agreement that, “Look, if you think you need 21 or 24 satellites for safety flight, that’s fine.” If that’s how you want to have it for the Aviation Safety System, Department of Transportation gets to make that call, and FAA.

But for the use of everyone else, we know the right answer is somewhere around 18. And everyone else has to get to a decision of a healthy system there. Why do I say that low number? Why? Because there is an 18th, 19th, and 20th, and a 21st, sitting in a barn ready to launch, with Space Force acting like they’re unaware, not prioritizing it because it’s not M-code. Although there’s an improved M-code on it. I’m not pushing for President Trump here, but this is a launch, baby, launch thing. We need to launch those four things. It’s clinically insane that Space Force won’t prioritize this launch. And by the way, we complained about having an Air Force, so we got a Space Force. Air Force didn’t prioritize this launch either. So this is a five-year effort to not do the right thing by two services.

This will give us a significantly wider bandwidth to work in, and improve signal structure. More accurate and resilient systems, probably 30 times harder to jam, mathematically. I have to turn to the DB experts on that, but I think somewhere around there. Look, Space Force needs to get its act together, stop this lethargy, and launch those. And I would say that’s fantastic if they do it, but of course we’re not done because the Department of Defense has also screwed up it’s oversight and management of Raytheon, which is eight years into a two-year project to get the OCX system up and running. I think there’s a great 2017 report where the response to the GAO hammering is, “We’ll have it done within two years.” Well, that was seven years ago. So now we’re here. And every year, by the way, every March they’ve moved it a March. So March ‘22 to March ‘23, March ‘23 to ‘24. Now it’s March ‘25. I think they’ve gone out of cycle and moved it to fall of ‘25.

Maybe we’re getting close, but Raytheon needs to get off its backside and stop screwing this up and get the operational control system for the L5 up. Again, authorized in 2010, fully funded in 2016. This is unacceptable behavior. It’s not how the Chinese work, that’s for sure. So we need to do that. We need to get the GPS III satellites launched, get DOD and Transportation to agree what’s a healthy constellation, and get Raytheon to get the OCX going. If those three things happen in 2025, we’ll solve a lot of problems. Now, look, I sound negative. Well, I am negative, but I am slightly optimistic that our decades of dysfunction are coming to an end. Because I do think we’ll get there.

And when we get a healthy 18- or 21-satellite network up with L5 on 18 or 21 satellites, we’re going to really improve. . . The critical infrastructure sectors will have access to it, allies and partners will have access to it, it’ll reduce the jamming and spoofing that our weapon systems experience. Now, look, you have to put the L5 antennas in things. And I’m not going to pretend that we’re going back into GMLRS, guided missile launcher rocket system, rounds and putting in L5 antennas. This will take time, but at least we’ll be on a path, a glide slope to solution. But really, at this point, relying on OSD to do oversight of Space Force and itself to get this done is a failure. So Congress needs to really ride them hard, and then Congress needs to turn on Raytheon a little bit here and say, “Look, this is unacceptable behavior. Get this done.”

End of 2025, we could be healthy, but only if Congress pushes hard, passes some stuff in this NDA and in the next NDA that holds these ones accountable, holds hearings on this issue, lights fires. Space Force can easily throw this on a launch, just in their prioritization, they choose not to. And I’ve heard recently they’re thinking of launching one soon, that’d be great, but really, we’re three or four years into a screw-up on four satellites. They should be getting all four of them up this spring, this summer, period. All right, so a lot of pessimism flavored with a tiny bit of optimism that we might get there this year. Thanks.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Well, thank you for wonderful presentations. In a minute, we’ll hear from Commissioner Simington with the keynote address, but before, if there are any urgent questions that the audience would like to ask our panelists, please have at it. And let me get a microphone circulated, and please identify yourself when you ask your question. In the back there.

Bob Winkler:

Hi, it’s Bob Winkler from Kratos Defense. Quick question. It sounds like from the panel, at least the last two speakers, that L5 seems to be the quickest way possible in order to get some type of a solution up. I’d like to one, confirm if that’s true, and then two, for the follow on, Space Force is spending a boatload of time and effort trying to come up with an alternative pathway that Congress gave them last year to bypass the palm cycle and get something in a quick start direct up on orbit. And that’s the resilient GPS system, which doesn’t sound like it has L5. I’d like to get a comment on that as well.

Mark Montgomery:

I’ll jump in first. Yeah. Yes, get hot on L5. I think I was pretty clear about that. I just think at this point, other solutions are going to go slow. Look, am I opposed to other options out there if they’re fiscally managed? No. I’ll also say skipping. . . The only thing that, I think, is more risky than the current FUBAR procurement system is to skip the procurement system right now, because I just think they haven’t demonstrated an attention to. . . They’re a brand new agency, Space Defense Agency, or the Space Force acquisition, I worry a little bit about them running rampant without that. What I think is we need congressional oversight. And look, Congress has to be hard. We had talked to Senator Warren, she has to be hard on Raytheon. That’s not a natural feeling for the Massachusetts delegation, but they need to be. They need to hold these guys accountable. This is unacceptable behavior.

Dana Goward:

Yeah, I think we definitely need to do anything we can to make things better. But you said solutions. So there really aren’t solutions, there are things we can do to mitigate the problem. Like any wicked problem, there are a series of things that you can do to manage it rather than solve it. We can certainly do L5, we should make things better in space as much as we can, but at the same time, I think if we’ve continue to focus PNT entirely in space, it’s doing the same kind of thing and expecting a different result. So I think we need diverse sources. They’ll take longer. It took us 50 years to get where we are with GPS, but if we don’t start now, we’ll never get there and we’ll have the same kinds of things that we’re experiencing now.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Mr. McDowell.

Robert M. McDowell:

And I know we’re eagerly awaiting. . . Oh, sorry, just to answer, eagerly awaiting Commissioner Simington as well, but I want to make sure you understand. I think there’s pretty much unanimity that all of the above is the way to go. And I don’t want my remarks for anyone to think that L1 should be abandoned. It should be part of the solution. You do have, as you saw with some other slides, operators operating in the L1 band that can triangulate and help determine, like Iridium and SoTellUs. The SoTellUs solution there is one of many, and that should be considered as well.

There is no one silver bullet, golden bullet, call it what you will, magic solution to all this. But I think the premise of the first part of your question is, yeah, we’re so far along in the construction of our United States L5 GNSS system, why don’t we finish it? It’s like having the four walls of a house built, the foundations laid, and even the beams of the roof have been put into place. You just need to put the roof on, finish the job. It’s not that far, so we should finish the job.

David Willauer:

Hi, David Willauer with the Transportation Research Board. Great presentations, I really learned a lot. We’re putting together a workshop this winter in February about the vulnerability of the nation’s digital infrastructure. So if this is the digital GPS system, we need GPS to run the nation’s transportation infrastructure, so this is a very timely presentation for me to hear as we’re planning this workshop. And as a longtime navigator myself, I remember when we used to use Loran-C to get around. Celestial navigation is still in use, I used it last month on a trip from Galveston to Corpus Christi to try to teach my sons that they can get from A to B without the navigation system electronically. Tell me a little bit more about what you said about Loran-C, or Loran stations. Is that still in the mix as an alternative? Because I thought that those stations were all dismantled some years ago, but Loran was very much in use in years past.

Dana Goward:

Right. Well, there’s a little bit of a background there. So in 2004, President Bush said, “Get me a backup to GPS because when it goes away, our national and economic security is going to be in the toilet.” So the directive didn’t read exactly that way, but that was the sense of it. So folks that were working for me at the time, when I was in government, spent a number of years working in the interagency, did a study, and decided to upgrade the Loran-C System to eLoran like Russia and China have right now, and South Korea and some other folks have. So that was the solution, and the entire interagency agreed on that. The Deputy Secretaries of Defense and Transportation announced that this is what will be going forward. DHS said, “We’ve got this. We’re going to take Loran-C and give it to Critical Infrastructure Protection and just transfer the money over and they can upgrade it to eLoran, and we will have met the president’s mandate.”

So in the transition between the Bush and the Obama administration, the Office of Mismanagement and Budget. . . Sorry, that is a branch of the Office of Management and Budget decided that instead of moving the $36 million from Coast Guard to the Department of Homeland Security Critical Infrastructure folks, they would just zero that out in the budget. Of course, this was done late on Thursday night. Folks had until Friday at noontime to protest. Admiral Thad Allen, who you may know, was coming up in the Coast Guard at the time, went around to senators, the new secretary and said, “This is a bad thing. It’s a small number. Dutch boy’s finger in the dike. I can’t do that. Every engineer and technologist in the government agrees we need to do that.” The OMB folks said, “Trust us. We’ll take care of this next year. We just need a small savings, deleting an old system for the new president.’”

Of course, as you can guess, next year never came. So a couple years later, Congress wrote and said, “What are you going to do about this GPS backup thing? And Obama administration said, “Yeah, yeah, we’re going to do the eLoran thing like we said.” But then of course, continued opposition from OMB, and quite frankly, opposition from some in the Department of Defense because they didn’t want anything in the budget competing with very, very expensive GPS programs, have prevented any progress on that. And in fact, even in 2018, Senators Markey and Senators Cruz, which I understand defines bipartisanship, sponsored and passed the National Timing Resilience and Security Act of 2018, telling the Department of Transportation, “At least get us a terrestrial timing system to back up GPS if nothing else.” Of course, it was provision of funds being available, and of course, OMB has prevented any request related to that from the Department of Transportation.

So here we are with a solution that was identified almost 20 years ago still being opposed by folks within the administration. And I think you mentioned Congress needs to act. When we talk to our friends in Congress about that, they tell us, “Look, we did what we could,” and this probably applies to DOD, too. “Congress can only do so much. If the administration is dug in, then unless it’s a high visibility thing, unless little Susie has died, and little Susie has not died in this particular field yet, almost in Sun Valley, but little Susie hasn’t died yet, then there’s really not much we can do.” I’m a member of the President’s Position, Navigation and Timing Advisory Board, and we have this summer sent a note to the Deputy Secretary of Defense and Transportation, who we report to, to the effect that the real problem is that the governance structure over the last 20 years has not kept pace with great power competition and the importance of PNT and the vulnerability of our PNT in this country and the huge risk we’re taking by not paying attention to it.

It’s a nice way of saying that, “You guys let the lower level bureaucrats just run with this and have not been paying attention.” Because any structure can work if you have energized, engaged, informed senior leaders that are making sure the country’s protected. And in this case, it’s just not. A lot of political and sociological reasons. We have a hard time taking action to prevent bad things from happening. There were over 140 commercial airliners hijacked before 9/11, but we didn’t harden the cockpit doors. So yeah, it’s just a bad situation overall, where we’re at. And still, senior leadership within administrations have not paid attention to this. Lots of technology, lots of ways forward, lots of ways to manage and mitigate the problem, but they have been stymied on 20 years. Did you hit my hot button? I think you did.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

Thank you very much.

Dana Goward:

Sorry.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

We’re going to have more Q&A after we have our keynote address.

Dana Goward:

I apologize.

Harold Furchtgott-Roth:

No, no, no, no, no. This is perfect. This is perfect. Okay. He’s had a very distinguished career both in and outside of the Federal Communications Commission. I would say of all of the leadership of the Federal Communications Commission, Commissioner Simington has focused a lot of attention on space-related issues, including those that we’ve been addressing today about GPS. So it’s a great honor for us to welcome Commissioner Simington here to the Hudson Institute and to hear your comments. Thank you so much.

Nathan Simington:

Well, I appreciate that kind introduction, but it’s been even better to listen to the incredible panel discussion today. I have the good fortune to come here with prepared remarks from my excellent Chief of Staff, and as you can see, I’ve extensively marked them up as well as taking around 700 words of notes on my computer. So it’s been extremely informative for me. In any case, I’m honored to discuss such an important issue with such an esteemed group today. I really liked the focus that we’ve had today on the T in PNT. It’s a dependency that is, in some ways, from my perspective, even more critical than the dependency on P, which goodness knows, is severe enough. Just think about all the cell towers that are relying on finely slicing spectrum, think about the HFT dependencies on Wall Street and the possibility of a flash crash, so getting a T backup is absolutely vital. This is a case where the silent utility might-

Nathan Simington:

. . . backup is absolutely vital. This is a case where the silent utility might’ve become a little too silent. We’ve gotten used to taking it for granted as though it were a natural phenomenon, rather than a complex system that, like any complex system, and just drive around a city sometime, tends to decay over time without adequate maintenance. And that’s to say nothing of active interdiction and denial. So unfortunately, GPS vulnerabilities, as this panel glaringly highlights, are becoming one of America’s biggest security issues. Even the most seemingly benign use of foreign technology can become a security threat. As all of you surely know, GPS developed and controlled by the US military was once the only satellite-based global positioning and precision timing system in the world. But now it’s been challenged and even threatened by foreign alternatives like Galileo, GLONASS and BeiDou. So supporting these systems is sometimes a requirement for device manufacturers wishing to operate in any place other than the United States.

So between the economic incentives such as economies of scale for manufacturers to have a single model for all markets, and the fact that these positioning systems sometimes offer higher precision and performance than American GPS, it appears that many American businesses and consumers are knowingly or unknowingly relying on these foreign systems in their operations. So you might ask yourself, “Well, where’s the risk? After all, these are receive-only systems that do not involve transmission back to the satellites.” Let’s set aside the high-accuracy two-way mode in BeiDou. But if these timing and positioning systems are being used to guide precision industrial and commercial processes in the United States, then obviously our adversaries could potentially cause widespread disruption by shutting down access within the United States, or even worse, intentionally spoofing and returning incorrect data to American receivers of their signals. As highlighted on today’s panel, we already see those things happening today. It’s not science fiction, it’s present reality.

So I personally believe that the FCC can play a role in rectifying this. Thus, the FCC needs to better understand whether, when and how terrestrial handsets might currently connect to foreign satellites for the provision of unregulated data services. Fortunately, thanks to the dedicated work of former Congressman Mike Gallagher, the FCC has initiated an investigation into this. It’s an ongoing Enforcement Bureau matter, so I cannot speak to its progress, but I sincerely hope that the investigation results in allowing the FCC to better understand how GPS and other GNSS is used in the United States. So for example, consider an activity tracker application, relies on GPS and other location services to track how far and fast someone runs. If such an application is downloaded by a consumer on his or her cell phone, the FCC should know whether that application uses the phone’s ability to connect to a foreign navigation service constellation in order to operate and therefore in order to potentially exfil data.

If so, it seems to only make sense that the FCC should consider a fulsome regulatory framework for any such service that connects to foreign GPS with regularity. While the FCC’s part 25 earth station rules govern whether and how domestic satellite providers connect to foreign satellites, those rules have not otherwise applied to terrestrial wireless providers who are not generally governed by the part 25 satellite service rules. As a result, the FCC has little insight into, for example, whether and how terrestrial handsets may connect to foreign satellites for the provision of data services that fall outside of the FCC’s jurisdiction, and if so, whether and how the FCC should address it. The Enforcement Bureau investigation aside, from the FCC’s current perspective, it’s unclear whether most terrestrial providers even know if their devices are receiving foreign navigation services or RNSS signals outside of the context of 911 location accuracy for a handful of providers. And since GPS and other receivers are operating above 960 megahertz or below the 30 megahertz can get an exemption from equipment authorization, the FCC therefore also has little insight into whether Apple, Samsung, other handset manufacturers are in fact taking steps to turn off foreign GNSS receivers before handsets ship to terrestrial providers in the United States.

What’s more, given the active secondary market, which is cross-border, there’s even less knowledge about the movement of such secondary market devices. Furthermore, if the GNSS receivers are turned on without a terrestrial provider’s knowledge, the FCC has no perspective and no way of getting any into whether and how a terrestrial provider would know if a customer is using an application that connects to a Chinese, Russian or other foreign navigation system. Although I would note that that pretty much clears the floor because we already authorized Galileo in the United States. So these are answers that the FCC just doesn’t really currently have, but which it must pursue as we venture into governing this nascent service.

So we’ve had some discussion today about the reporting structure for GPS outages, and I would note that the FCC is not generally a primary player in this loop. So we do have a statutory mission to protect the airwaves. So that seems like it’s sort of a conspicuous failure. On the other hand, GPS, in some ways it’s a military system. In some ways it’s a civilian system. In some ways it’s a federal system. In some ways it’s an international dependency. So it may have fallen through the cracks in a regulatory sense. I don’t know if the right answer is for there to be a dedicated organization within the FCC Enforcement Bureau that can participate in a clearinghouse for this, whether the FCC itself should host a clearinghouse for this. But in any case, the FCC has got to use its powers to protect civilian air wave integrity.

And right now when it comes to GPS, not only are we not really doing that, we’re not even in the loop for the parties that are attempting to rectify this. So early after I was seated, I got concerned about this issue, not because I’m some sort of great thinker about engineering issues, but because I happened to get put in touch with Dale Hatfield and he was of course worried about it. So I started calling around and trying to figure out how the FCC learns about GPS outages, and it turns out that the usual, most common pathway is that someone overflies a GPS outage, calls it into the FAA, it makes its way back to the Stanford GPS center, and then at some point someone may or may not tell the FCC. So I said, “Hm, if I were sort of a disgruntled youth, as many of us once were, then there’d be absolutely nothing that would prevent me from blanking out an L1 signal by taking a suitcase-sized device, taking it to the middle of Dupont Circle, and then watching everyone miss their Ubers.”

It really is that simple. We have a system that was designed at a time when it would’ve been relatively technically expensive and technically burdensome for your average punk kid to engage in GPS disruption. However, I’ve interviewed professors at Virginia Tech who tell me things like, “Yeah, we have our students build StingRays out of 35 bucks of parts ordered off Alibaba. It’s a routine third-year electrical engineering project.” We’re no longer operating in the world where cheap, complex devices cannot be used to suppress GPS, at least the L1 signal, as we’ve heard from several speakers today, and since that’s the case, the FCC needs to wake up and realize that this is in fact the present-day operating conditions, and we can either sit around and argue all day about how to tariff the remaining 300 users of a copper plant in the United States, or we can get a little bit more real about protecting this critical dependency.

Anyway, so that’s my first request. If you have thoughts about how the FCC could be a more effective organization and partner and how we could leverage our statutory authority in this area, then please call my office. I’ve got two staffers here and my email’s on the website, so I’m easy to get a hold of, and I promise I’ll take your concerns seriously. Okay, so the next question is, from my perspective, since the FCC is operating primarily in a commercial and public-facing way rather than with regards to the federal services and to the security services, my next question is what does it look like to have commercial convergence on PNT backup standards? Obviously, the DOD has a point of view on this, in fact has many points of view on this, and there are many areas that are being technically explored, and we’ve heard some presentations today on exactly what some of these technical means of responding to this would look like, such as non-cooperative use of multiple satellite constellations, and just distilling something out of that.

I have no idea what is reasonable on the terrestrial level, if it would be something like that, if it would be a use of BPS. I’ve got no idea what’s going to be the cheapest antenna structure, the cheapest data reporting structure, what’s going to meet the standards for commercial role liability that are broadly acceptable at the best price point. But I do know that I would love to see commercial convergence on PNT backup. I’m open to the question of whether it should be a regulatory push or pull. I suspect that given the FCC structure and our clientele, it would be de facto a regulatory pull rather than a push. I think it would be hard for us to go out and mandate that any particular PNT backup be used until it’s already become a de facto industry standard, and we’re pushing it perhaps onto the holdouts.

But again, I’m open to discussion on those points. The point is that as we’ve heard, civilian equipment is often de facto military equipment or it’s de facto defense equipment, or it’s simply where the R&D that will become part of the next generation of defense tech is taking place. Sometimes, as we’ve seen in the case of private launch, a capacity emerges in the civilian sector that was prior a federal sector capacity. And again, that might generate a certain amount of angst but on the other hand, if you’re the guy who can put rockets up, then the United States government has no choice but to give you a call. So again, what I’m saying is I don’t know if it’s going to be push or pull, what convergence on commercial standards looks like, but I would love everyone’s thoughts on that as well because it’s clear that this is a longstanding need and that we shouldn’t sit back and wait for the L5 constellation to get fixed and solve it for good and always.

And as we’ve heard, although completing the L5 constellation would be great, there’s a lot more to it to get actual PNT reliability under a variety of conditions including potentially average conditions. I guess the last point I’d like to make regarding lack of L5 constellation completion. So the United States remains about 50 percent of the entire world market for satellite services. That’s an incredible number. That means that the United States is the de facto commercial satellite regulator for the world if we choose to be, because you need an FCC license to transmit to and from US ground stations and that means that among other things, we can regulate your orbital debris, we can regulate lots of stuff about you. So either you abandon the US market or you come talk to the FCC. And in fact, I think that we’re probably a better place to do business in terms of getting business done quickly than the ITU.